A little bit of war profiteering

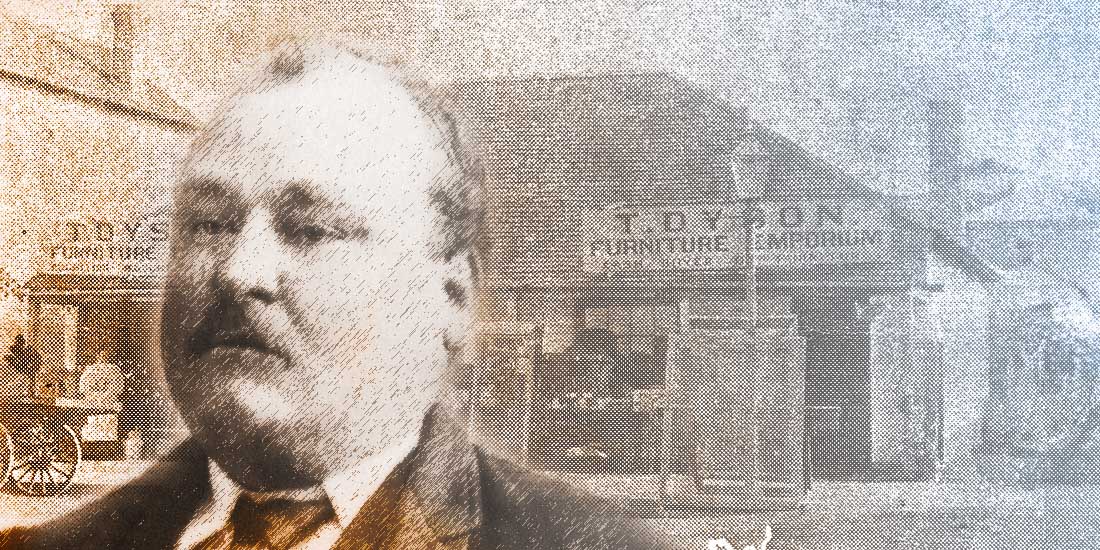

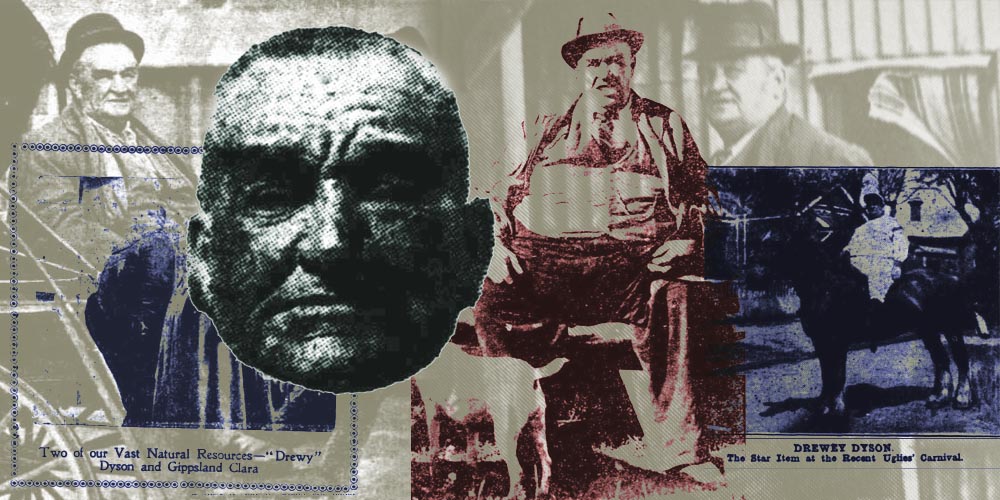

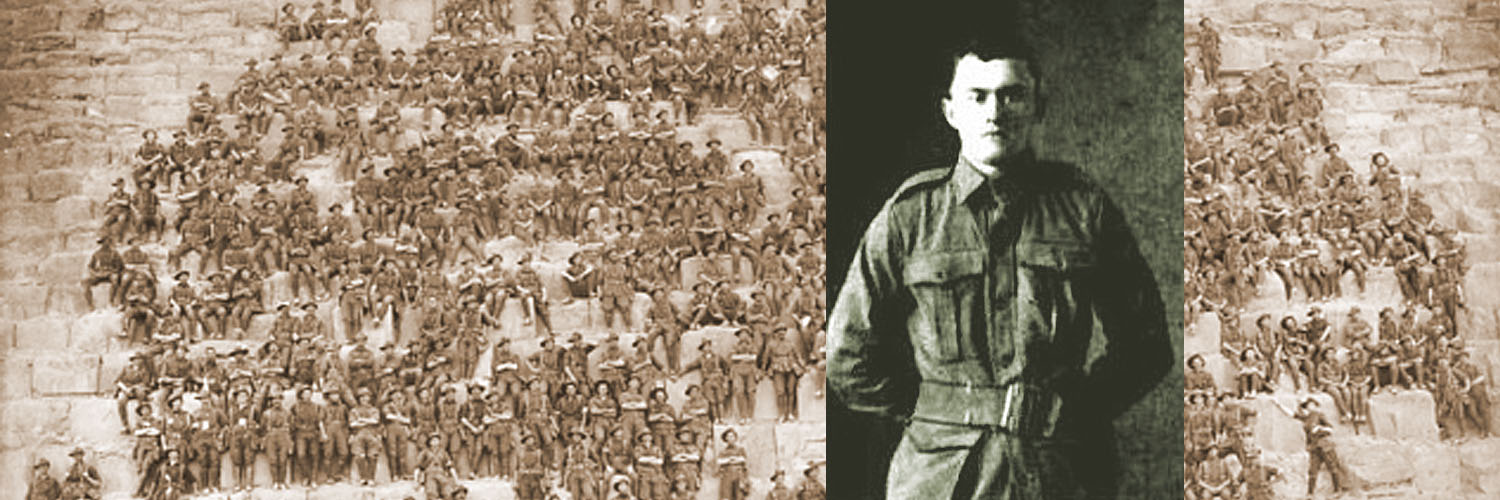

Sam Dyson was was among the first to sign up for the Great War and was among the first quota of Western Australians in the AIF. He would be one of the first on the beach at ANZAC cove, and would survive for his Dad to tell that story. His father was Andrew “Drewy” Dyson and it’s important to remember that any story mentioning Drewy will always end up being about Drewy.