Sometimes its just a name that piques your interest. Sometimes names are all you have. The Sons of Australia Benefit Society was formed in January 1837 and it’s final meeting was held in August 1897. For sixty years it seemed to be an ever-present feature in the social fabric of Perth, Western Australia— and then it was gone.

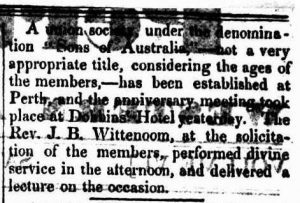

Most of what there is to know about the society comes from the contemporary press. There was no mention of it in the Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, supposed paper of record in the colony, until it’s first anniversary (and then it was a snide one). This was certainly due to the rivalry between that rag and the editor of the Swan River Guardian, William Nairne Clark. It had not always been that way— back in 1833 the Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal had written in similarly approving terms of a benefit society newly established, named the Western Australian Union Society, but that same issue, it reported that W. N. Clark had resigned as secretary of the same. It does not seemed to have long survived his departure.

Nairne Clark should not be confused with Mr William Nairn, one of the society’s first trustees, nor should Mr William Nairn, blacksmith by trade, be confused with Major William Nairn, a prominent soldier/land owner in the colony’s earlier days. Mr Nairn’s son James was also a foundation member and both were members of the society’s cricket team that defeated an XI comprising the Gentlemen of Perth in a memorable match on 18 June 1850, despite the weather and the poor condition of the cricket ground. The umpire on that occasion was Alfred Hawes Stone. If Stone himself had been on a team it would have been with the Gentlemen, I suspect. He was a solicitor and Registrar of the Supreme Court. His younger brother, George Frederick Stone, if he had been playing, would probably have been on the Sons of Australia team, as in addition to being an up-and-coming lawyer and former Registrar of Births, Marriages and Deaths, he was also active behind the scenes in the formation of the society back in 1837.

It might be asked why did he interest himself in a similar manner. The answer was very simple, He felt it to be his duty. When only a child he was witness to an accident which befell a poor, honest, hard-working man, who, falling from a three-storey ladder, broke his leg. This man was helping to build the house in which he (the chairman) was destined for many years to live, and the poor fellow had in his rough but pleasant way always displayed a liking for him as a child. When the poor man was taken to the Dispensary close by I went also, and being anxious to know what the poor man would do for a living while he was unable to work, I inquired from one and the other till I found that he belonged to a Club, the members of which all put by something per week into a bag, while they were in work, for the benefit of themselves bye and bye, when they should be sick or out of work.

G. F. Stone, quoted in The Inquirer and Commercial News (Perth, WA : 1855 – 1901) Wed 29 Jul 1868 Page 3

I was so struck with this, and so relieved at the thought that my honest hard-working friend would not want while he was laid up, that as soon as I was old enough, I became an honorary member of the same society, and to this hour I believe my name still remains upon the books of the Society. (Loud cheers). From that time I have been always interested in the prosperity of similar institutions. I was at the formation of the society called “the Sons of Australia,” which in its infancy was thought to be a political society, and was regarded with an evil eye, but time has shown the vast amount of good that has been done by it, and it is now the wealthiest society in the colony. Like all other kindred endeavours for the public good, it had met with many discouragements, but he had done what little he could in conjunction with one or two others, and it was now a most flourishing society.

Stone alluded to distrust from the authorities in the earliest days and I would like to find more examples of this concern. The society was formed in the last miserable years of Governor Sir James Stirling’s administration. Although his noisiest critic (said W. Nairne Clarke, and the Swan River Guardian) were pretty well suppressed by 1838, it is extremely notable that the colonial chaplain, J. B. Wittenoom, was an early and public supporter of the new organisation. I think I have mentioned before that on the surface, Wittenoom should represent everything I detest about the early establishment in Western Australia. He was the only representative of the officially sanctioned state religion of England in Western Australia in the early colonial years, yet he seemed to spend as much, or more, time as a magistrate and school teacher, and yet more energy on social activities or looking after his family’s interests. When pressed, he had a petty streak that manifested itself when challenged by Wesleyan Methodists and the Evangelical factions in the Colony of his own Church of England— That said, his challengers were pretty damn insufferable themselves. Wittenoom had no reason to like W Nairne Clark or his paper, but neither did he have any reason to love the cronies around Stirling’s administration, who barely concealed their contempt for him even as they appreciated his geniality. In short, Wittenoom was no man of the people, but within his limitations he tried to do what was best for those within his remit, and for a supposed religious leader was refreshingly free of religious fervour.

It’s hard to find anyone find anyone with a bad word to say about G. F. Stone, chairman of the Sons of Australia in its first year — even Nairne Clarke is mild in his criticism, and by rights, being both in the legal profession and a government appointee to boot, he should have been a prime target for an all-out assault (Not being virulently attacked in the Swan River Guardian is about the highest praise you can get). But G. F. Stone was part of the ruling class and the whole purpose of Sons of Australia was self-help for the artisan class. Stone himself, modestly concedes he was only one of the founders. The others were probably:—

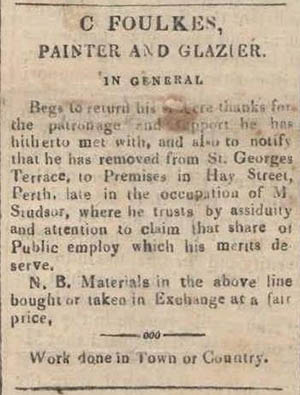

Charles Foulkes, a painter and glazier; William Nairn, a blacksmith; John Robert Thomson/Thompson/Tomson (no relation), a carpenter and joiner, William Rogers the Elder, a storekeeper. These four, along side Stone, were the first recorded managers of business for the Sons of Australia.

Charles Foulkes came to Western Australia in February 1830 on the Protector, a widower with an eight-year-old daughter. In 1837 he was forty-one and in addition to being the inaugural secretary of the Sons of Australia, was also secretary of a mysterious organisation called LODGE 1: The Philanthropic Society of 40 Friends. Now, its possible that this is what the Sons of Australia Benefit Society was called in it’s first year. There is no mention of it in the papers before or after 1837. A LODGE 2 spin-off was attempted in Fremantle the same year but vanished without trace.

- Now confirmed: Lodge 1 & The Sons of Australia are one and the same.

The fourth anniversary meeting of the “Sons of Australia Benefit Society” took place on Tuesday, 19th instant, and we were well pleased to observe the unanimity and good feeling manifested on the occasion. The members, to the number of about forty, moved in procession to the Church, accompanied by the Rev. the Colonial Chaplain, who delivered an eloquent and appropriate lecture, illustrative of the benefits and objects of the Society. The reverend gentleman impressed upon his hearers the necessity for good conduct, by which alone the very useful objects the members had in view could be carried out, and expressed his approbation of the general state of the Society.

The members returned from Church in the same orderly manner, to dine at the United Service Tavern, where an excellent dinner was provided for them; Mr. Charles Foulkes in the chair. After the cloth was drawn, the usual loyal toasts were given, and the evening was passed in harmony and good fellowship. The Rev. the Colonial Chaplain intimated that his Excellency the Governor had requested him to convey to the members his cordial approval of the objects of the institution, and his satisfaction at the flourishing state in which it then was ; in proof of which a donation from his Excellency was at their service in aid of the funds.

This Society was instituted in the year 1837, at the instance of a large body of the operative class, and is for the relief of members in sickness, old age, and infirmity, and for the providing certain sums for the decent interment of the members. It is the first institution, in this colony, of a kind that has done so much good for the labourer, mechanic, and artisan, in England, and in other old countries, and it seems to us to be especially requisite in this land, where there is, as yet, no public institution for the reception of the aged and infirm. The rules and orders by which the Society is regulated appear to have been very carefully drawn, and entirely free from objection : especially we are glad to observe that all political or religious discussions are expressly forbidden.

Inquirer (Perth, WA : 1840 – 1855) Wednesday 27 January 1841 p2

That same anniversary meeting, the society unfurled their new banner, under which they would march for many years to come. Like their organisation itself, their emblem was a shameless knock-off from the International Order of Oddfellows: A hand touching a heart. By 1841, the Sons of Australia were thoroughly respectable. Stirling’s successor as Governor, John Hutt was himself the society’s patron, and later that same year, future treasurer and chairman James Dyson would arrive in the Colony (but no record survives of when he actually joined).

But for Foulkes, he would not have the chance to benefit from what he had started; he resigned his offices in 1844 and the next year followed his grown daughter to the new colony of South Australia where she married. It was not a successful move for her father:

[…] The thing which it is chiefly important that our readers should know, is, the statement which Mr. Steel (who has returned to this colony in the Paul Jones) makes relative to the prospects of employment in Adelaide, and the condition of those persons who, deluded by specious representations, and their own restless spirits, have lately gone to South Australia. Mr. Steel says that hundreds of persons are walking about Adelaide unemployed; that Mr. Foulkes (whom all our readers well remember) has not had a day’s work since his arrival in Adelaide; and that there is scarcely one of those who left this place for Adelaide who would not gladly return, if it were in their power.[…]

Inquirer (Perth, WA : 1840 – 1855) Wed 15 Oct 1845 Page 2

Worse, a copy of the Inquirer made its way back to South Australia…

It is quite evident that Mr Steel was not suited for this colony. The statement of hundreds of people being idle in Adelaide is grossly false. Instead of such men as Mr Steel, we want some good laborers[sic]. For example, if all the bullocks, drays, and draymen, were transported from Swan River, we could guarantee them employment.

South Australian (Adelaide, SA : 1844 – 1851) Tue 11 Nov 1845 Page 3

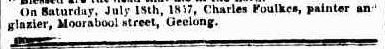

Steel had been verbaled and as he had planned to return to South Australia with his family, he was furious. But Foulkes had been identified by name and he was stuck there as a walking example of a b—y insular West Australian. By 1852 he was declared insolvent. At some point between then and his death aged sixty-one, he took the only course of action open to one with no options left—he moved to Victoria.

It will not be often that one of my research subjects get to speak in their own voice, but Charles Foulkes is one rare example who has become just a little bit more than a name on a page. He seems to have liked a drink occasionally— On one occasion in Ougden’s Tavern during 1835 he was involved in an altercation where he was drunkenly accused of being a convict. Foulkes took great offence (although it was not he who was up on assault charges later on). He must have had some sort of not-entirely-respectable-reputation for when he stood to speak at a temperance meeting held in 1841, the Methodist minister in the chair attempted to suppress him hard.—

Mr. Foulkes rose to make a proposition. The Rev. Mr. Smithies said he should not do so.

The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal (WA : 1833 – 1847) Sat 6 Nov 1841 Page 3

Mr. Foulkes,—I a British born subject —am I to be put down in this way before I have opened my mouth ? As a minister of the gospel, Mr. Smithies, you are bound to hear me candidly and dispassionately; I have not disgraced myself; I came here with a friendly feeling to the society ; and I have a strong interest in its welfare. I do no advocate it by gab, but in my breast. I feel how its best views can be promoted.

Mr. Smithies—I will show you how you are interfering with the progress of the meeting by authority forthwith, (one of the rules of the society was then read which enforced the propriety of conveying instruction on the subject of temperance, and not admitting any disquisition.)

The chairman requested Mr. Foulkes to proceed if he had any thing to state in conformity with this regulation.

Mr. Foulkes—I have been put out, for every body knows that all men’s ideas ebb and flow. Mr. Smithies is a good sort of man in his way, but he is not in my line of life, or he would not have said I have no right here ; I am perfectly sober, and have not had a glass of spirits in my house for many months. But if I were drunk I should be the proper man to remain here, and to be listened to; it is not the sober you seek to reclaim but it is the drunkard, and the more drunkards you could assemble the better. I don’t come here with any cut and dried bits of speeches; I tell you my mind and you don’t seem to like it—now to disappoint you, as you at first put me out, I’ll not make a speech at all. (Laughter.)

Mr. Smithies—sit down, or I will say something will make you look queer.

Mr. Foulkes—I say, say it! you come it very queer!

Leave a Reply