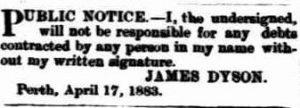

In the last six months, something odd happened. Many (not all) of the shadow wives and husbands of the Dyson children — AND a parent of a parent too — inadvertently stumbled out of the historical shade.

I have written up some of this (but it is nowhere near ready to go), the rest is being assimilated into the book… so before we all die of old age — here is a brief taster of some of the latest discoveries in the works.

Emily Bates

Andrew Drewy Dyson’s girlfriend and mother of his child.

All that was known about her previously:

- Attended a theatre performance in Perth where Drewy Dyson made a scene.

- Gave birth to his son Andrew Samuel Dyson a few months later in 1894 on the family property near Dog Swamp.

What we have now:

- Emily Bates was born in 1875 to a desperately poor family in south London. The family name might have been Betts rather than Bates. She sailed to Western Australia on an immigration ship named Gulf of Martaban in 1891.

- Apparently employed by the Dysons as a domestic servant — getting pregnant by her boss resulted in some horrific internal injuries after the birth of the child, and that child was then taken away by her employers as their own. She fled to the recently established Salvation Army Women’s refuge in Perth, and that organisation smuggled her out of the colony for a new start in South Australia.

- She continued working as a domestic servant in Adelaide, but was continually in and out of hospital for the rest of her life until she died there in 1926. She was 52 years old.

John William Stevenson

Second husband of Hannah Smith, nee Dyson

What we knew before:

- The couple hooked up (but never actually married) in northern Tasmania. He was a hotel publican. Hannah gave birth to a child at Launceston in 1893.

- They return as a family to Perth, Western Australia. He was next involved in a public scandal involving fraud against the government railways by the Perth Ice Company. He was a clerk for that company.

- After the charges against him are dropped, the family moves to Kalgoorlie (as you do) but Hannah Stevenson died there in 1902, aged only 45, and John Stevenson himself drops dead only a few year later in 1908. They leave a 14 year old orphan girl living in a Kalgoorlie brothel, as the hotel the family lived out of was known to be…

What we have now:

- John William Stevenson immigrated to New Zealand from Scotland as a young man and set up in Wellington as a merchant, then as a sharebroker.

- At age 36 (but looking ten years or so older) he abandoned respectable career, wife and child for a life of adventure in the Australian colonies.

- It took his lawfully married first wife seventeen years to finally pin him down and serve the divorce papers. The case was heard in absentia by the court in New Zealand, so by the time the divorce was finalised in 1902, his second wife Hannah had already been dead two months.

- The story of his 14 year old daughter has a surprisingly optimistic ending…

Henry Seafield Grant

One more drunken wastrel.

What we knew before:

- Only that Mrs Mary Jane Robinson, nee Dyson, also went by the name Mrs Grant, and went to her grave as Mary Jane Grant-Robinson

What we have now:

- Henry Seafield Grant was a young and up-and-coming theatrical impresario who threw off his showgirl wife in Victoria for a life of thespianism and heavy drinking in the boom-time gold-rush colony of Western Australia.

- Several years later in Perth (1903), his luck ran out after he got blind drunk one evening. He went indoors and searched for something in the wardrobe. Instead he found the barrel of a revolver pointed at his nose. He had wandered into the wrong house. Not only was the residence not his own, he had managed to be caught red-handed burglarising the family residence of a serving police constable.

- He never crawled out of the bottle again.

- He rented a house in East Perth where Mrs Jacky Robinson nee Dyson lived as his “housekeeper”. She always denied she was married to Harry Grant, who is described as the “Manager of a Club”.

- Jacky’s family detested her housing arrangements. A nephew by her younger sister Mabel, trashed his auntie’s house and wanted to beat the crap out of Grant at 1 a.m. in the morning.

- But for the prurient press coverage of this family dispute after it ended up in court (1921), we might never have learned of the existence of Harry Grant, or that Mary Jane was fostering a seven year old child in his house.

- Robert Jordan was the son of a soldier who was killed in France in 1916. The boy’s mother had recently (1920) married another man. What happened to this child in the aftermath of Mary Jane’s own death two years later in 1923 is not immediately obvious.

- A year after Jacky died, Grant remarried. He died in 1939.

The identity of Mrs Jane Dyson’s parents

What we knew before:

Bugger all.

What we know now:

It is Jane Develing no more.. read on!