There was nothing particularly unusual about the citizens of Perth suing each other in the civil courts during the 19th Century. It was more out of the ordinary not to be embroiled in some sort of legal action at any given moment. Being able to sh*tpost on social media instead, as a means of passing the time, lay a century or more into the future.

Wed 29 Apr 1857 p2

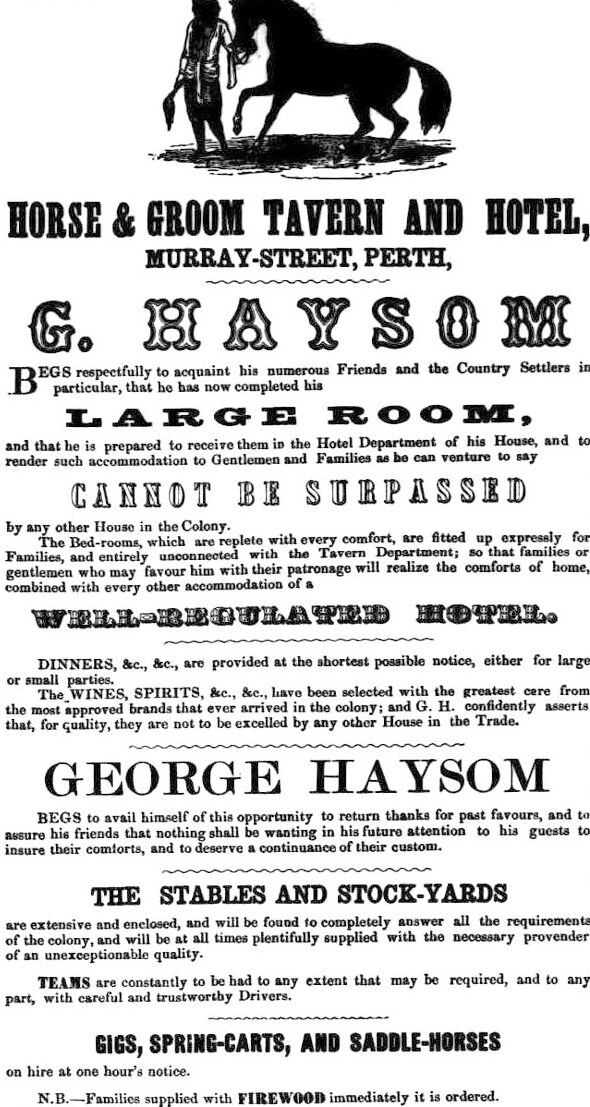

George Haysom (1822 – 1868) was a successful carter, publican, horse-breeder and wheelwright — among his many positive personal attributes. His eternal fame in Western Australian history should be inviolable, for he was the first man ever in Perth to roast a bullock in public AND be the owner of the first ever horse in the colony to die of snake bite (that anyone knew of).

Roasting a bullock: Another rabbit hole to dive down

On Tuesday, 9 May 1854 it was Mr George Haysom’s turn to appear before the Commissioner as a defendant. He was represented this day by lawyer George Frederick Stone. His two prosecutors retained George Walpole Leake to represent them.

Back in January, Haysom hired out one of his horses to this pair of speculators so they could transport some trade goods from Fremantle down to Bunbury. His horse was returned to him a couple of weeks later, but he still awaited a settling of the account, and that was when one of the customers returned to him with a proposition to sell him the cart used for the run — some of the proceeds from the sale would be returned to him to cover what he was owed.

After some intense haggling over the cart’s value, they agreed on the sum of £25. To seal the deal, Haysom produced a bottle of ale (at his own expense) — “to wet the bargain” — That was how he rolled.

Haysom had only been in possession of his new ride a couple of days when he was accosted by the other man who demanded to know why he had possession of “his” cart.

Soon afterwards, the first individual who sold him the cart returned and begged him to let them both have it back. Haysom was fundamentally a decent sort. After a conference in the small parlour of his “Horse & Groom Tavern” with both the partners present this time, he agreed to return the cart if he was repaid his accumulated debt — a sum of £7 11s 2d.

They agreed. Haysom was not paid in cash, but with a promissory note due at six weeks in the future. The following evening he received a letter from Mr George Walpole Leake, the lawyer for one of the partners, demanding damages for the detention and injury of the cart.

[…]what the deuce did you send me such a letter for ?”

… Haysom now wanted to know.

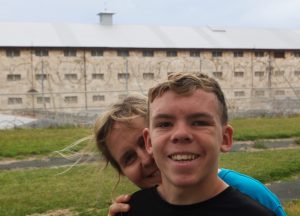

The case was heard in the Old Court House building (the one impossible to take seriously once you have heard someone ask if it is the public toilet block for the Supreme Court gardens). The testimony of all the witnesses, who included Haysom and both his prosecutors, were presented in excruciating detail three day later in one of the local papers.

All that really needs to be explained is that one of the prosecutors had sold their cart to Haysom without consulting his co-owner beforehand.

The verdict was duly delivered in Haysom’s favour — as it should have been. None of this would be remotely interesting were it not for the summing up of the prosecutor’s legal representative after the last witness had delivered his testimony and was thoroughly cross-examined over it. Remember, Leake was being paid to advocate on behalf of the plaintiffs in this case…

Mr Leake said he felt so disgusted with the cross-swearing which took place in that Court, that in the present instance he must request of His Honor to commit one party or the other for trial for perjury —he did not care which.

The Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News, 12 May 1854, page 3.

One of his clients was subsequently sent to gaol for perjury.

His eccentric wit and the justice he dispensed was not always conventional”

Says George Walpole Leake’s entry in the Australian Biographical Dictionary.

Indeed!

And here is where this article might ordinarily have concluded.

George Haysom is an important figure in James Dyson’s story, alongside that of the Sons of Australia Benefit Society, and the history of the Perth City Council. — but it is his (carefully unnamed up to now) prosecutors that deserve a bit more attention.

Theodore Krakouer (1818 -1877) was the one who initiated the legal action against Haysom. He was a Western Australian ticket-of-leave convict about who a lot has already been written because he has descendents famous for playing Australian rules football.

He was the wronged party in this court case, however the one who he should have taken to court was not Haysom, but his erstwhile business partner, a shadowy figure by the name of Edward Hale(s) Taylor. It was he who sold the cart they co-owned while his partner was otherwise detained. It was Taylor who was subsequently sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for perjury after the civil trial.

Krakouer deserves to be better known, but as far as I can tell, no one has ever put together all the pieces of Edward Hale(s) Taylor‘s story before. A rough attempt begins next.