Winterbottom’s End

Joseph Winterbottom was the old bastard pursued by Oldham police across the border from Lancashire into the West Riding of […]

Joseph Winterbottom was the old bastard pursued by Oldham police across the border from Lancashire into the West Riding of […]

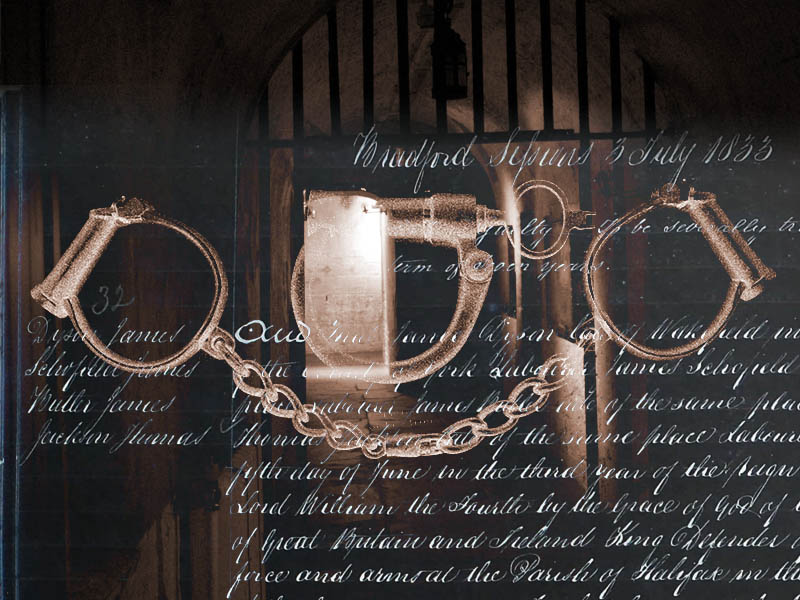

18 June 1833. Halifax, Yorkshire. A heinous crime had been committed the previous evening, Mr Robertshaw had been viciously attacked […]

Every family should have a good ghost story, the Dysons are no exception…

A second tale of taxidermy and ratbaggery, this time in the old country of Lancashire.