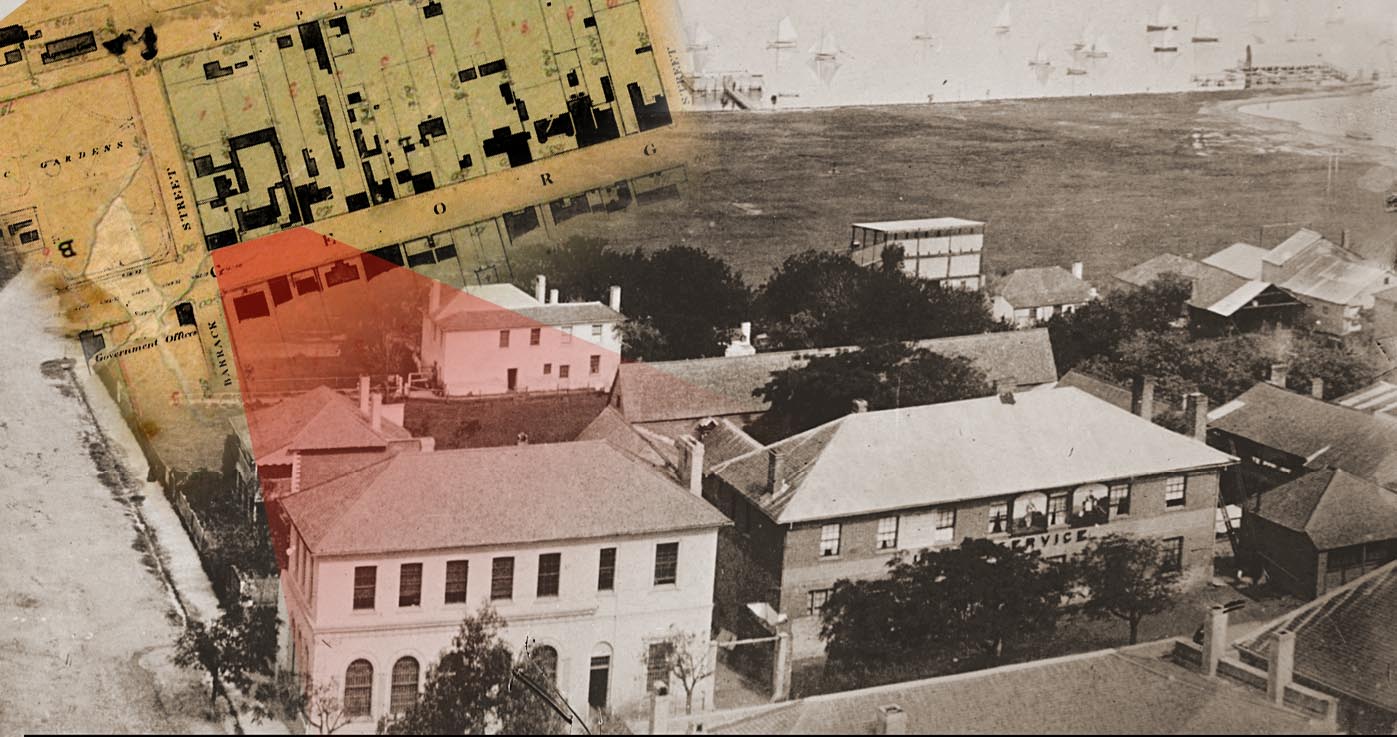

The story of the original United Service Hotel & Tavern

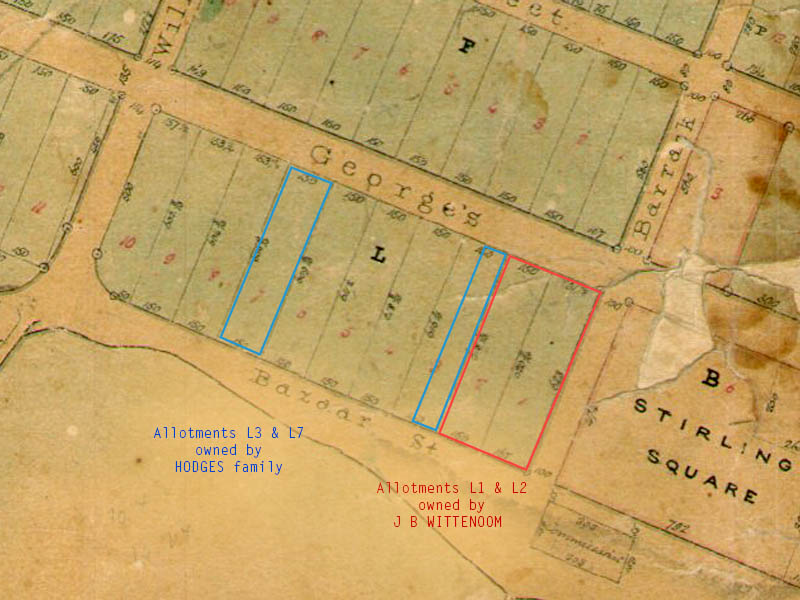

Perth Allotment L3 in the town of Perth, in the Colony of Western Australia, was originally gifted to colonial merchant and all-round important person George Leake, by virtue of him already having a lot of money. He swiftly on-sold it to a consortium consisting of a Portuguese boatman named Joseph Moore and a Mrs Hodges. Moore had the money — Mrs Mary Anne Hodges had the advantage of not being a filthy foreigner and thus was permitted to be granted title over property (even if she was a woman*) in what was then very much an infant British settlement. The property was fully assigned to Mrs Hodges by the year 1832 — Year 3 of this town of Perth’s existence. By then, a dwelling house, bakery, outhouses, drains and fences had been erected on the lot and an invisible line separated the Hodges’s family property from that owned by Moore.

* I am being sarcastic. Don’t @ me.

Mrs Hodges did have other family with her in the Swan River Colony. Her daughter and son-in-law lived under the same roof as she, as was her husband. She was no widow. George Bell Hodges, and son-in-law James Dobbins were both serving in the 63rd Regiment of Foot, part of the British Army then assigned to Western Australia. The Perth Barracks, where they would otherwise have bivouacked, was only a short walk away from Mrs Hodge’s property on the other side of St Georges Terrace and Barrack Street.

On 1 January 1833 Mrs Hodges applied for and was granted a publican’s licence on her property and what became known as the United Service Hotel came into existence.

There was a reason why it was Mrs Hodges’ name on both title deed and liquor licence instead of her husband. Serving soldiers were not supposed to be involved in trade, just as Joseph Moore could not be allowed to openly own real estate when he was not a naturalised British subject.

This prohibition on going into business, or owning land when in the army— was certainly not applicable to the officer class. This class were probably also the ones insisting the loudest that their subordinates must not allowed to to follow their example. The commanding officer of the 63rd regiment had got a free grant of land from the Governor as soon as he stepped of the boat in 1829. Captain Frederick C. Irwin’s estate of Henley Brook in the nearby Swan Valley was one of the best in the colony. Those under his authority hated him. The wider population of the settlement got to know him too during his first brief period as acting-governor. They burned his effigy in celebration when he handed over to his successor.

At least one future historian will make the mistake of believing that because Hodges was eventually able to be the name on a title deed that he must have been an officer, and a Captain too, no less. His fellow Privates would have found the very idea hilarious, and laughed as hard as they did when Irwin (by then promoted to Major, and Commandant of all British forces in Western Australia) desired to inspect his troops in full dress uniform and regally fell off his horse on the parade ground.

So it was Mrs Hodges who had to be both the name and the presence behind the counter for the time being while her men were on other duty. She was the baker, general store proprietor, and after 1 January 1833, holder of a publican’s licence. Her as yet un-named public house on L3 would soon be known as The United Service Hotel.

Her husband was still in one of those Services (but presumably off duty) during August 1833, when, as he was serving beside her behind the counter of their general store, a labourer rolled in through the doorway inebriated as a newt and agro to boot. William Glover was there to pay a bill for some sugar. All produce in the Swan River Colony of this time was exorbitantly expensive and sugar was no exception. Glover attempted to pick a fight over the price, but Hodges refused to rise to the bait. Glover next attempted to get a rise by questioning the fighting prowess of the British soldier.

Hodges was aged in his early to mid-forties. His record was good and he would have known that if he did not attract any negative attention to himself, he would soon be eligible for a honourable discharge after so many years of service. His son-in-law, Dobbins (half his age) had no such concerns. Suddenly Private James Dobbins was standing before Glover with a hand on his shoulder prepared to throw him out the store.

Unfortunately, slouching in the doorway, and immediately outside, were some of William Glovers’ own comrades. Dobbins went down under a pile of bodies. A female voice (whether belonging to Mrs Hodges or Dobbins is not recorded) raised the traditional call of hue and cry to summon the assistance of the town constable. That call was “Murder!”

“Corporal Dobbins was murdered down at Hodges’s”

The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 28 Sep 1833 p. 153

…was the message delivered across the road to the soldiers in barracks. The doughty men of the 63rd Foot swiftly mobilised and descended on Mrs Hodges’ store…

Dobbins was not deceased. Some bruises would be the extent of the injuries suffered by any of the parties involved in this affray. The extraordinary feature of this episode is not that Glover then brought a charge against Dobbins for assaulting him (charge dismissed, Glover ordered to pay court costs) but that Glover remained alive to even contemplate such a course of retribution.

There was an attempt made to arrest Glover by Hodges, but it failed…

He was sitting down in my shop bleeding when Hodges and two other soldiers came and said Glover was a prisoner, I refused however to give him up unless to a Civil authority. Hodges appeared as much excited with anger as Glover was.

The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 28 Sep 1833 p. 153

This shop belonged to a Mr James Solomon.

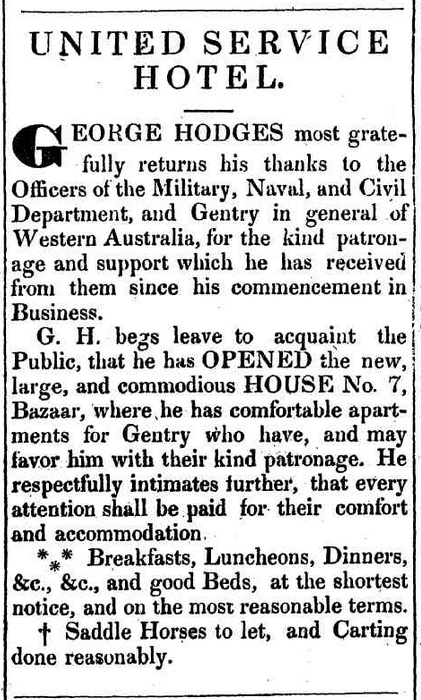

The first mention of the name: United Service Hotel appears in a newspaper dated 5 July 1834. It must have been a familiar name by then, for this title was address enough alone to advertise that an auction of a nearby property was to be carried out at that location. The allotment now being offered for sale in this advertisement was L7, just down the road, which the Hodges family promptly purchased. L7 was registered to the name of George Bell Hodges, so he was, by now, no longer a private soldier, just a private citizen.

With far more room to expand on this new site, the United Service Hotel was transferred to this fresh location.

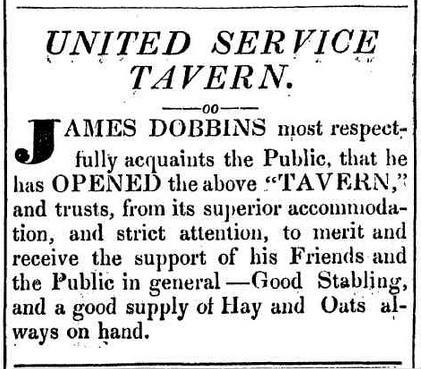

However, they still possessed the infrastructure on Perth Allotment L3, and this location remained physically closer to the military establishment— and a clientele whose guaranteed pay days were until recently officially known as grog money. This original structure was rebranded as the United Service Tavern, and who better to run it than Hodges’ own kin, now he had bought his way out of uniform too?

The seeds of misfortune germinated almost straight away. Joseph Moore, Portuguese boatman and silent co-owner of L3, died very suddenly late October 1835. The Hodges found themselves having to deal with a new partner who wanted to cash in their equity in their unexpected new possession as soon as possible. The question was resolved in court by the beginning of the year 1837 but not in the Hodges family’s favour.

While this setback was being sorted (presumably at great expense) — another merchant, the one who had loaned them the money to purchase L7, attempted to auction the same out from underneath them all because of a book-keeping error on the merchants’s side. George Hodges was understandably irate and took Lionel Samson to court over another related book-keeping matter. Hodges lost that case again, as he usually did, but retained ownership of L7. Now he had antagonised the principal supplier of produce sold in his establishments.

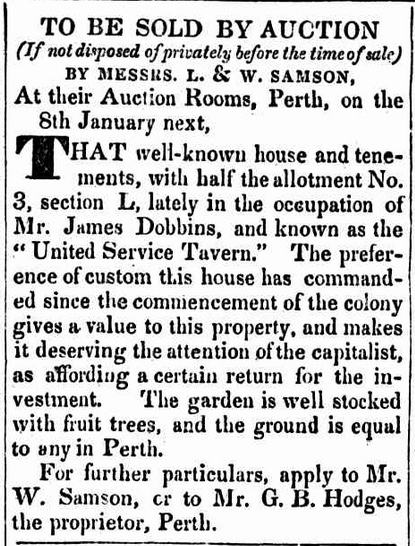

The family may have had no choice other than to put the remainder of the original site of the United Service Hotel on L3 up for sale at the beginning of 1840. Also included was the good will, custom and the very name of the establishment his son-in-law had run for him — seemingly very successfully — for the past five years. (Notice it W[illiam] Samson, not his brother Lionel, that assisted at this sale.)

The name of the hotel on lot L7 evolved over time from the United Service Hotel, to Hodge’s United Service Hotel, to just Hodge’s Hotel — then a complete re-brand as the Royal Victoria Hotel, (after the new British monarch in 1837) — shortened inevitably to the Victoria Hotel. But by then it was too late to save the family business in Western Australia. The Victoria Hotel was sold by the end of the year 1840.

Sale of the Victoria Hotel.—This old established house and extensive premises, with well stocked garden, &c, was sold by

The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 12 Dec 1840, p. 2

private contract, yesterday for £1,300.

The proprietor has made a sacrifice in disposing of this property in consequence of the opposition created by the establishment of a cheap eating house, called a club; on the opposite side of the way.

The Hodges family regularly announced their imminent departure from Western Australia over the next few years until most of their number did indeed board the colonial Brigantine Emma Sherrat, bound for a new life in India on 19 February 1845. This vessel travelled as far as the island of Mauritius. Once there, another vessel would convey them the rest of the way to wherever that would be.

The merchants of Perth were anxious to learn how well their produce on board the Emma Sherrat had sold in this potentially lucrative new market for their wares only a few days sailing from home. The days passed, then weeks, then months, with no message that the harbinger of all their futures would ever return. Sailing ships could and did vanish without trace. Four months later the Emma Sherratt finally returned to Fremantle.

In a nice piece of bastardry, George Hodges delayed her return to Western Australia by taking out a lawsuit against the vessel’s master, Captain Harding. The court case over some unrecorded matter had delayed the return trip by seven weeks. Hodges himself was never going to return to Western Australia, but he had left some family back in the Colony remaining to get out.

When Dobbins and his wife (Hodge’s daughter) eventually left Western Australia for Mauritius on 20 August 1845, it was also in the steerage hold of the Emma Sherratt. Captain Harding might have fed them to the sharks en-route to the island for all the trace in the historical record that remains afterwards of that couple.

If you know better, do let me know!

Mrs Mary Ann Hodges (nee Eckley?), who for my money is the real hero of this testosterone drenched tale, died and/or was buried in Kolkata, West Bengal (then part of British India), on 21 April 1865 at the age of 70. George Bell Hodges lived another three years before joining his wife in the same burial plot on (or about) 20 December 1868. His social status at the end of his life was recorded as being a gentleman.

Addendum:

It turns out that Irwin knew all about Hodges’ wife’s business acumen all along:—

In this town are several comfortable inns. One of them is kept by George Hodges, a discharged soldier of the 63rd regiment. This settler owes his prosperity in the colony chiefly to the prudence and good management of his wife. Having a knowledge of baking, she commenced in a very small way at Perth ; and, being noted for her steady conduct and integrity, merchants and masters of vessels entrusted her with considerable quantities of flour, for which she paid with punctuality. From her success in this, and other undertakings, her husband has now the principal bakery and inn, besides a general shop.

Frederick Chidley Irwin, The State and Position of Western Australia, Commonly Called the Swan-River Settlement, 1835, p50

Hi Alan

Had so much fun reading your article re the Hodges….question for you….is the William Glover you refer to, the same person who arrived in 1829 on Marquis of Anglesea? If so, he is my g.g.g.grandfather….his son William went to NSW and bred a large family, mainly in Sydney, Newcastle, Port Stephens.

Cheers

Lorna

Hi Lorna,

Thanks for the kind words… I had fun writing it! Looking up William Glover now in the WA Bicentennial dictionary and it has to be the same person who arrived on the Marquis of Anglesea in 1829… or his nephew, with an identical name… who arrived with him on the same ship!

Hi. Interesting piece. George Hodges is my husband’s 3rd Great Uncle and we have seen the published stories of some of this but not necessarily how it hangs together. We have been looking to find more about Mary Ann Hodges and the daughter. I wonder what you may have. Also, what about Godfrey Bell Hodges Jnr of whaling fame. There is a bit of doubt if he was the actual son of the senior George and how he came to be there as he wasn’t mentioned on Sulphur arrival. He also reappeared in 1846 as if he had gone to Mauritius and returned

Hi Wendy,

Thank you! My interest in the Hodges family was sparked due to their connection with the “United Service” … dare we call it a franchise? … and how there seemed to be an interconnected story that had not yet been told. Since I wrote this I haven’t found any additional information about the family that I have not already posted.

I’ve seen the name of Godfrey Bell Hodges about, suspected he (or they) were a related somehow, but not investigated much further… regrettably.

I got the impression the family of George came from England, but the family of Godfrey came from Ireland. Maybe they are part of the same family but separated at an earlier generation? This is just speculation on my part, I’m afraid.

I would love to find out what happened to the Dobbins part of the family!