Five minutes of searching the internet revealed no consensus on the origin of the name Dyson. Thankfully this is not what this article is about. Regardless of the original etymology or geographical location of a theoretical common ancestor, (and while it would give me no pain at all to be able to trace my ancestry all the way back to a female cattle rustler in the West Riding of Yorkshire) the earliest credible ancestor I can identify from the surviving records is that of Simeon Dyson from Crompton, near Oldham in Lancashire. His son, Ely (or Eli) was born during the reign of Queen Anne, some time before April 1701.

For several generations thereafter, the descendants of Simeon were predominately cloth weavers in the hilly east of Lancashire, occasionally spilling over the county borders into Cheshire to the south, or east into Yorkshire. The weaving of wool into cloth using hand looms was a traditional cottage industry in the region, and Simeon’s listed trade as a joiner—a specialised skill in carpentry—hints at his future family’s success in manufacturing the implements of the weaving trade.

Joseph Dyson (1783-1839) was born into a very different world to that of Simeon, his great-great-grandfather. King George III had comprehensively lost the American colonies and the spinning material of choice was now cotton. Staggering technological advances in the production process transformed a rural landscape into both an industrial and urban one. During Joseph’s lifetime, the transition from water power to coal and steam would have turned the damp wet country (the moisture being ideal for the cotton spinning process) from green to black. Joseph married Hannah Binns in the Church of St Chad at Rochdale, on 19 January 1804. His father-in-law, Mr. Andrew Binns was described as a Cotton Spinner which does not really adequately reflect the reality that he was not a weaving machine operator (skilled though such operators needed to be), but was actually an owner of a mill in his home town of Mossley.

Joseph seems to have had a varied career that involved quite a bit of travelling about the county. At the time of his marriage, his trade was listed as clothier, which suggests he was involved in the selling end of the cloth production cycle. By 1815 he was described as a cotton weaver, which again tends to down play his responsibilities as an overlooker—a factory floor supervisor. He made his residence on the outskirts of Oldham town, a district glorying in the name of Mumps. He owned at least six cottages on a small street that looped underneath the hill-side overlooking the main road out of town. It’s grand name of Regent Street seems somewhat overblown. Those six cottages (now long gone, as are everything else contemporary to him or his family on Regent street) probably was the heart of his cotton empire, as far as it went. The impossibly large number of occupants of this tiny street are mostly listed as cotton spinners in the 1841 England Census, which took place only a short time after his death. Dyson probably owned or sold the hand spinning machines worked by them in his cottages. His travelling work continued as a machine broker and a trader in cotton waste. When he died at home in Regent Street in 1839 he left his children an estate worth £2000… to some of his children at least.

His sons continued in the Cotton milling trade as Spinners, Overlookers, Managers and Yarn Agents— except one.

Of his nine supposed children, three appear not to have been born to his wife, Hannah—and at least one of those may have been adopted from his unmarried sister.

All the children that survived into adulthood were mentioned in his will, witnessed shortly before he died at his home on 13 July 1839, his long-suffering (inferred by the circumstances) wife having pre-deceased him eighteen months before. All the children were mentioned, except one.

- Thomas Dyson, born 1803 at Quickwood (Saddleworth) near Mossley.

- Andrew Dyson, born 1806 at Mossley.

- William (i), born 1808, died 1814 at Quickwood.

- John, born 1815, at Bough, Mossley.

- Mary, born 1822 at Mossley.

- Sarah, born 1824, at Oldham

- William (ii), born about 1826.

- Joseph, born 1828, at Mumps.

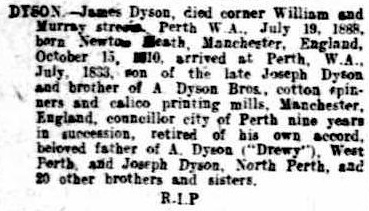

The missing child was James Dyson. He was reputed to be born in Newton Heath, a suburb of Manchester on 15 October 1810, but no baptism record has been discovered for him. Birth certificates are still a generation away. At least two of his siblings, John and Mary, are described as illegitimate on their baptismal records. In John’s case, Joseph is the reputed father, while Mary was probably the daughter of Joseph’s unmarried sister Betty. The second William Dyson also has a missing baptism record but, like older brother James, he indubitably existed. James Dyson is not in the 1841 census that locates most his siblings living together in Regent’s street, or working with their late mother’s Binns relatives. He was either in, or about to arrive in Western Australia at that precise moment. Essentially, there is no formal record tying James Dyson to this family in Lancashire. And that’s the way (I am sure) they wanted it. Informally, however:—

James Dyson in Western Australia, outlived all but one of his siblings back in Lancashire, and at the time of his death, and until her own in 1896, sister Sarah lived in Newton Heath, Manchester — the only definitely recorded member of his family to do so. She lived in a house named “Birch-villa” on Droylsden road. It’s name might a reference to to the family’s cotton mill founded after the time of her father and run brothers Andrew and Joseph. It was known as Bower Mill and was located in Hollinwood, equidistant between Newton Heath and Oldham, near the site of an old house occupied by the family called “Birchen Bower.” The house was famous for many legends including a real life mummy and ghost story. Today there is a motorway on the site.

But what had James done to be so comprehensively written out of the family story in Lancashire? Before him, James was a family name among the Lancashire Dysons. It was demonstratively “retired” after him. He was not the last bastard to be fathered by his father so it could not be that. There remained some memory of the family’s antecedents in Lancashire by James Dyson’s Australian children, and there may have been some (long lost) line of communication back to someone in the home country.

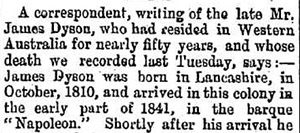

James arrived in Western Australia on the ship Napoleon in 1841, but the surviving passenger list for the January arrival at Fremantle from England does not mention him. But wait, does not the press clipping below say he arrived in July, 1833?

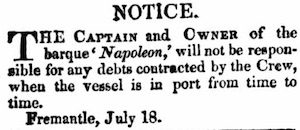

The year the colonial barque Napoleon visited Western Australia was most definitely 1841— she made two visits to Fremantle in that year, one in January, and the second in July. She is not to be confused with an American whaler of the same name also in the vicinity at that time. A passenger list for the January visit contains no mention of Dyson, although the ship sailed direct from England. From the second July visit, no passenger manifest has been located and the port of origin this time was quite different.

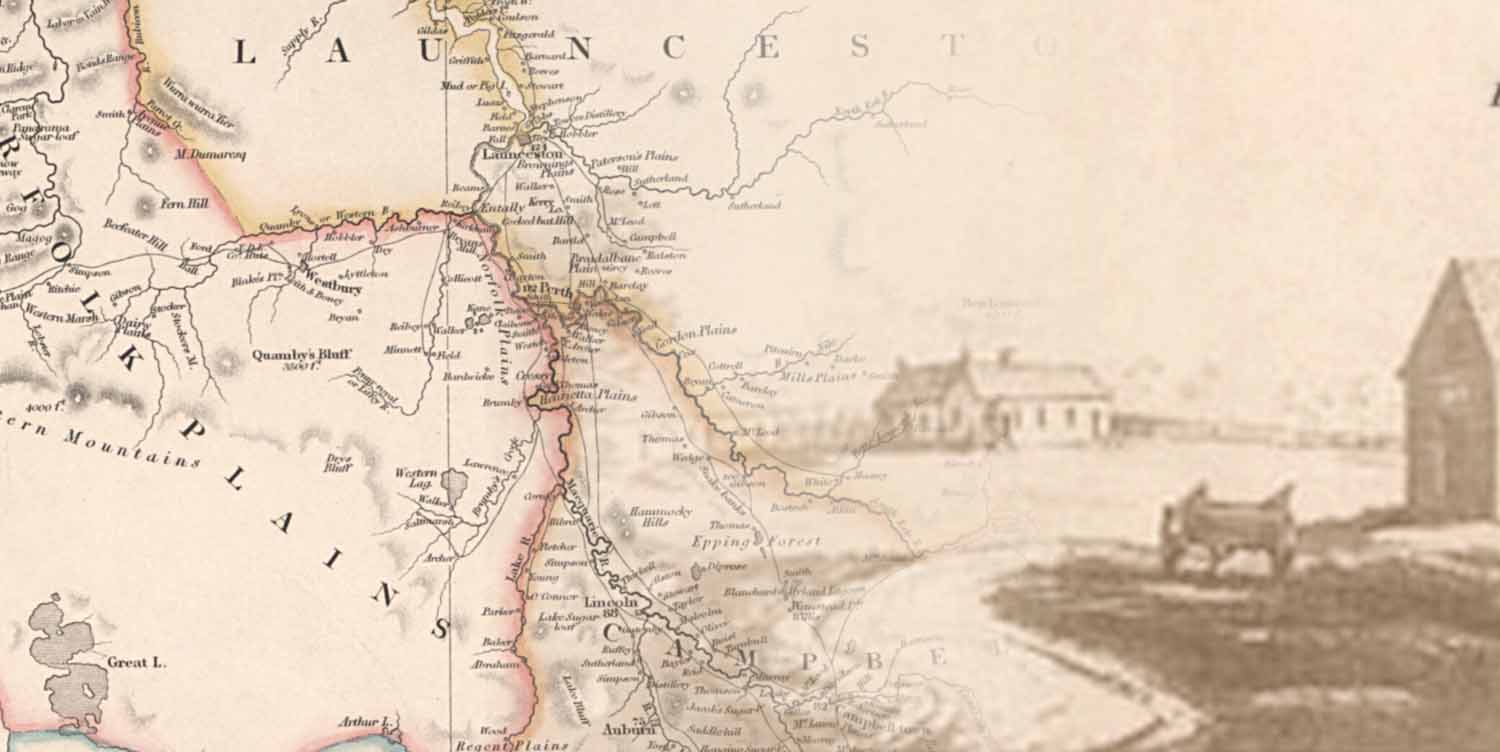

The Napoleon sailed from Fremantle in February 1841 and arrived in March at Launceston, Van Diemen’s Land. There she underwent re-fitting to be a whaler and sailed back to Fremantle in May, arriving on the 12 July 1841.

There was a man called James Dyson then living in or around Launceston in what is now known as northern Tasmania in 1841. Furthermore, there are distinct records of a young man called James Dyson who departed from England in January 1834 for the prison colony of Van Diemen’s Land. This James Dyson did indeed depart from Lancashire in 1833, never to return.

The circumstances of his departure were no doubt a massive embarrassment to his family, and more than enough cause enough for his father to wipe him out of the family inheritance, however his ancient cattle rustling antecedents may well have nodded with approval.