On a Roll

Was your ancestor a member of the Sons of Australia Benefit Society (1837-1897)?

Television and photo-plays have theme tunes. Nation-states have theme tunes which they call National Anthems. For most of Australia’s past […]

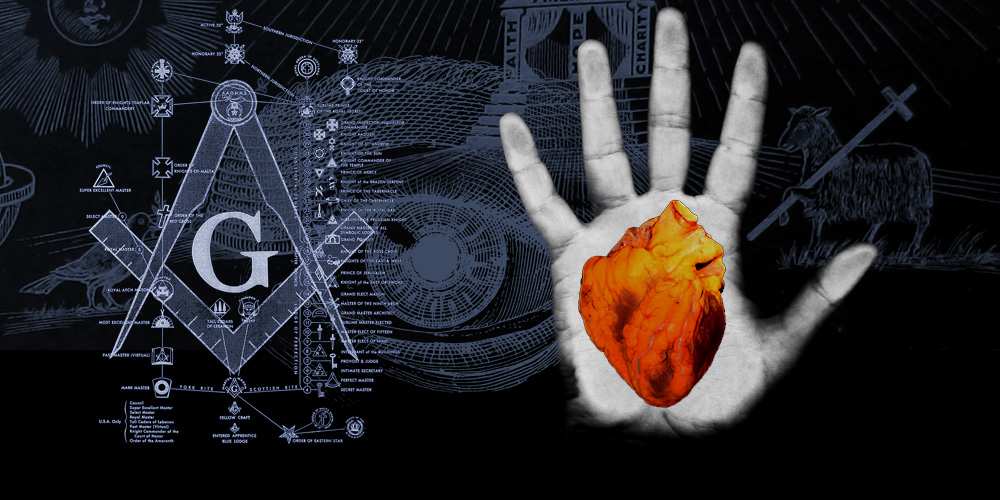

Sometimes its just a name that piques your interest. Sometimes names are all you have. The Sons of Australia Benefit […]

It seems like there was nothing the average man in Australia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries enjoyed more than […]