Dyson’s Corner (the Second)

Joseph Dyson became a husband and a father (though not necessarily in that order) during the year 1872. It was time for him to strike out and get a house of his own. Thus the second Dyson’s corner was formed.

There were many of them. These are the son and grandson of James, not his father.

Joseph Dyson became a husband and a father (though not necessarily in that order) during the year 1872. It was time for him to strike out and get a house of his own. Thus the second Dyson’s corner was formed.

There is currently no known authentic likeness that exists of James Dyson. He was a prominent man of his time— […]

The story of the corner of King and Murray Street in the city of Perth, Western Australia, continued.

Sometimes its just a name that piques your interest. Sometimes names are all you have. The Sons of Australia Benefit […]

It seems like there was nothing the average man in Australia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries enjoyed more than […]

The fairly grand former General Post Office building on the corner of St Georges Terrace and Barrack street, the the exact site of which had once been the original soldier’s barracks for Perth, Western Australia.

…About half-past nine last Friday night, my attention was attracted by a number of persons standing in front of prisoner’s […]

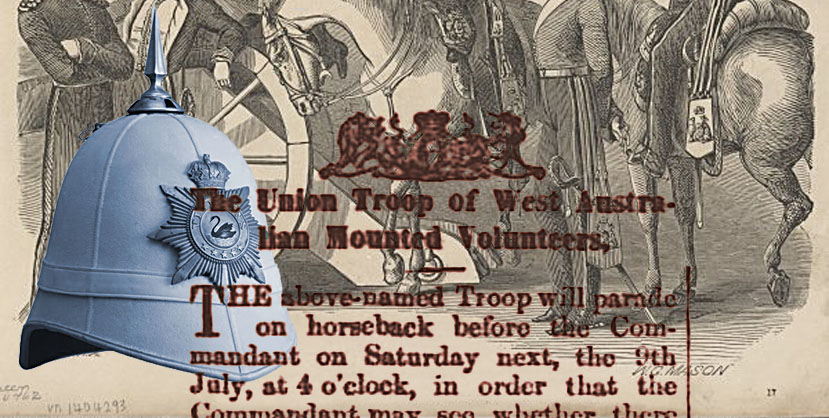

Silly names, even sillier hats, a missing Army rifle and a shotgun wedding?

Dorothy Dyson was the youngest daughter of Joseph Dyson junior and Jessie Christisen nee Strutt.

His older brother was dead, his younger brother was mad… It fell to Joseph’s lot to be his father’s heir.