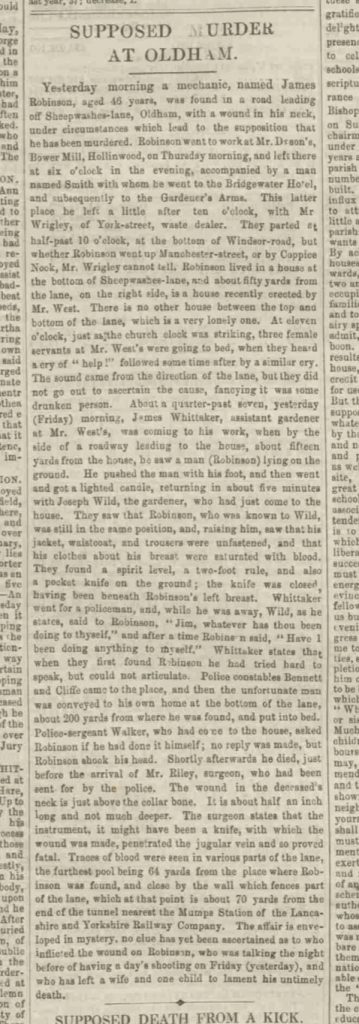

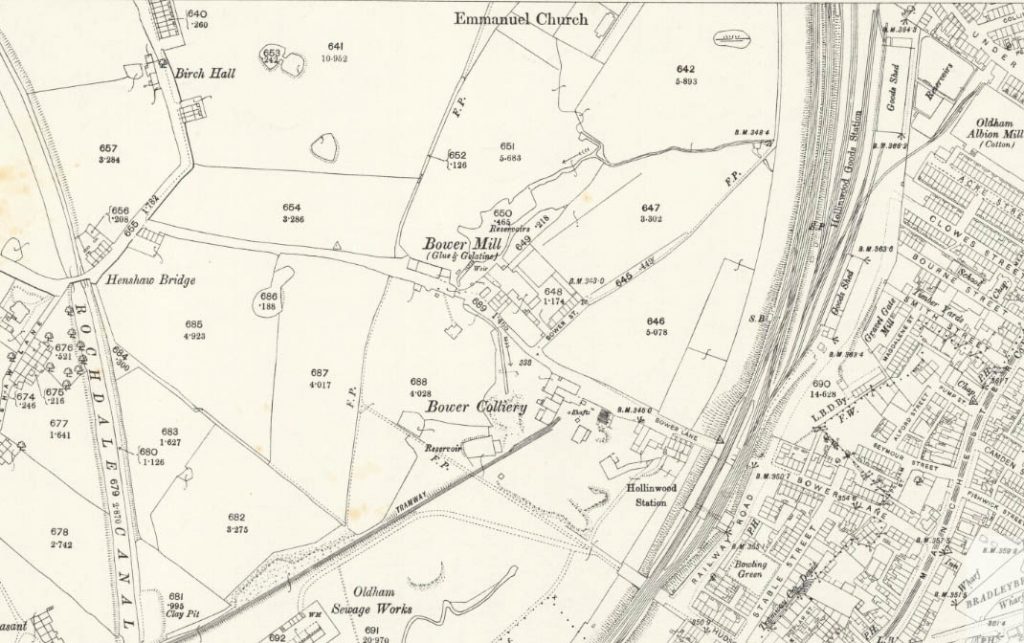

Birchen Bower in Hollinwood, Lancashire.

I could not believe my eyes when I first read about Hannah Beswick of Birchen Bower.

It was not that I could not believe in a ghost story — although that part of the legend I still find challenging — but that I could find a tale with so much in it: haunted houses, buried treasure, invading armies, a real-to-death mummy in the attic, AND find out I had an actual family connection to it all. That was the good news. More disappointing was attempting to investigate further and finding so few primary sources to draw upon.

The least suprising aspect of this tale was that there was a Dyson component to it. If any family was going to have a haunted house associated with them, it was going to be these Dysons of Lancashire, the siblings of the same James Dyson who was contemporaneously creating a new life for himself in Western Australia during the middle of the nineteenth century.

A DISMAL autumn evening. The mist hangs heavy on the silent landscape, and wreaths in ghostly folds above the stream. Along the highway rides carefully a man of sober garb and mien, who, passing the ancient Bower House, continues his way to a smaller residence by the river side of Birchen, Lancashire. “So she has left it,” he mutters as he glances back at the ancient residence, now but faintly outlined in the mist. “A goodly property ; and she fears the grave. Ha! who will inherit it, I wonder? And her money ? If rumour speaks truly, she has buried it.”

“Haunted Ancestral Homes” Illustrated Sydney News, Sat 1 Oct 1892 Page 12 (Trove)

If an army of hairy Scotsmen were descending towards you in the November of 1745, you would have buried your gold too (and maybe yourself as well, to save time) — you had only to look to history of how the Jacobites treated their own countrymen that last time, to know that no mercy would be shown to a rich Sassenach couple. But spinster Hannah Beswick and her bachelor brother John did survive Bonnie Prince Charlie’s invasion of Manchester with their property unravaged. John had— apparently— almost been buried alive; but his eyelids flickered just as they were about to close the coffin lid. He still predeceased his sister though, leaving her the manor house and farm of Birchen Bower in Hollinwood.

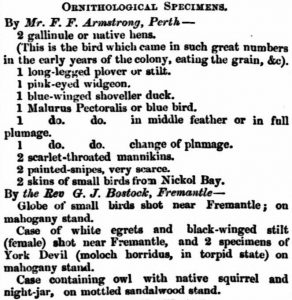

When she died, so the legend goes, she specified she was not to be interred. So her medical attendant (who did quite well out of her will, thank you very much), embalmed her instead. Dr Charles White was not one to let a good thing go to waste, so he put the old lady on display at his house in a clock case (to be seen for a fee, no doubt). Later on she ended up an exhibit in the Manchester museum. Late Victorian squeamishness eventually saw the poor old mummy buried in an unmarked grave in 1868. She had been above ground for 110 years.

These Beswicks died during the eighteenth century. The Hollinwood manor (but not the farm) passed out of the family’s descendant’s hands during the following century in November of 1834. The next owner (or maybe a tenant) of the manor building was Mr Samuel Wolstenholme, but he was declared bankrupt in March 1836.

A wing of the house was demolished, and the remainder was subdivided into tenements for cotton-spinning workers. When you consider all the old Lancashire cotton mill buildings now being transformed into supermarkets or luxury apartments during this twenty-first century, you will realise there is nothing new about this form of recycling.

Almost as soon as the old lady had been embalmed, reports of her ghost had began to be recorded around the old manor house and the adjacent farm. It was part and parcel of the legend of course, that her gold was never officially recovered. Unofficially, some items were recovered by various tenants over time, but none of them seemed to have got rich… or did they?

Enter the Dysons. James Dyson is out of this story. By the time Mrs Robinson, a descendent of Hannah Beswick on her mother’s side, sold sold the last of the property — James was on a convict ship to Van Diemen’s Land.

Then during 1839, the same year James’s father Joseph died, there were worrisome reports that Chartists were drilling in the fields outside Birchen Bower. It seemed revolution was in the air.

Fast forward a decade, and it is pretty much obvious that the world did not end in 1839 and at some point between the years 1843 and 1851 Andrew and Joseph Dyson, older and younger brothers of James Dyson respectively moved into the district and operated a cotton spinning establishment named Bower Mill. Andrew, his unmarried sister Mary and her two illegitimate children John and Edwin had taken up residence of Birchen Bower. The codicil to Andrew Dyson’s will made just before his death in 1880 gives a strong indication that he owned the whole place and the Mill as well. Although they had dissolved their partnership a decade earlier, Andrew left the property to Joseph. After that the trail has not been pursued…

So did the Dysons mine gold as well as spin cotton? Probably not. But it is fun to speculate. In the late nineteenth century Birchen Bower was demolished to make way for the Ferranti factory (now also demolished.) Bower Lane and Bower Mill were likewise flattened at a later date and a major free way dug across the site.

It is frustrating that I have been unable to locate an image of Birchen Bower in any form, or of Hannah Beswick herself (stuffed or unstuffed). It was ancient and had a whitewashed exterior according to an article dating to 1953 (the house, not the mummy). It is curious that while there were ghost sightings of Hannah during the Ferranti factory days, there don’t seem to have been any on the motorway. How odd.

There has been at least one book published on the mummy of Birchen Bower.