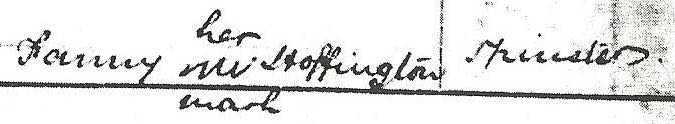

When I started writing my book on the Dyson family, very little was known about James Dyson’s first wife Fanny nee Hoffingham. They married in 1842, they had four children, the last of whom was an infant daughter who died in 1849, a year before Fanny herself (supposedly) died. The best guess as to the cause of death being complications arising from that last birth. There is no official death certificate.

Of her origins before their marriage there was no information whatsoever. The life and death of Mrs Fanny (or Frances) Dyson seemed set to be a sad paragraph in-between her husband’s convict past and his turbulent and drama rich second marriage to Mrs Jane Edwards, nee Devling. Her sole legacy might have been a trace of DNA passed on through the only one of her children to have a family of his own. Her life was anonymous. Only her passing was noted.

About a year after a television programme went to air in Australia stating that the first Mrs Dyson probably died (anonymously) of puerperal fever or some other common disease of the time, I was doing some research in the State Records Office in Perth, probing the police records in the hope of uncovering a bit more context to the frequent run-ins with the law a supposedly grieving widower Dyson was embroiled in during the early years of the 1850’s.

What I found left me stunned. Fanny Dyson was very much alive after the year 1850. She had left the family home and was incarcerated for a time in the Perth Lunatic Asylum. Her husband was being taken to court, for – among other matters – refusal to pay for her upkeep while in government custody. She in turn, refused to return to him while that seventeen-year-old girl who would eventually be his second wife was living under the same roof as her husband. It was a ghastly situation to which there might have been only one inevitable outcome: At some time in mid 1854, Fanny Dyson took her own life.

But the question as to who the former Fanny Hoffingham had been remained.

The servant class of early Western Australian colonial history were simply not talked about unless they did something dramatic (and/or illegal) to draw attention to themselves. They would not necessarily be mentioned by name, or at all, on the manifests of the ships they arrived on, being considered merely as baggage for their masters – or husbands.

I considered whether Fanny could have been one of the teenage orphan immigrants sent to Western Australia to fill the dearth of female domestic servants by The Children’s Friend Society at about the right time in the colony’s history. In the person of Frances Massingham, I though I might have found a match, but it did not take too much further research to disprove that theory. It was a fun theory while it lasted.

Then I discovered the existence of James Dyson’s outrageous fellow convict, granted her freedom the very same day in Launceston as he: The one-eyed former sex-worker with a conduct record that made Dyson seem worthy of a sainthood by comparison – Fanny Dewhirst. Also the man she was married to at the same time she married James – fellow convict Lorenzo Johnstone.

I dared not believe I had uncovered James Dyson’s first spouse’s true identity for a long time. Eighteen months of research later, I had the one thing I don’t have even for James Dyson’s convict past (Which now seems to be accepted by most as a proven fact.) – Two documents that independently connect the VDL convict with the Western Australian colonist. In common is the name “Overton”. As a name, it is found in relation to Fanny in a transcription of a Dyson family bible. There is no context for this. There is, however, a village in west Yorkshire called Overton. It is located within the Yorkshire parish of Wakefield. Wakefield just happens to be place the convict Dewhirst said she was from when interviewed on arrival in Van Diemen’s Land. This for me, was one coincidence after many that convinced me I had found the correct person.

There was also a faint trail of DNA connecting Fanny Dyson’s GGGG grandson to a branch of the Dewhirst family located in the right part of the world and from right time period. I personally distrust DNA matches extrapolated this far into the past, but it holds the hope of something approaching scientific certainty might still be arrived at, someday.

I’ve continued looking for that one fact that would conclusively prove Fanny Dewhirst was not Fanny Dyson. I’ve always known it would only take one piece of firm evidence to demolish the whole baroque structure of her story as I’ve reconstructed it. I was always prepared to be proven wrong. I still am, even after the following finally was made aware to me.–

Now, this might be true. If this claim can be proven, I’ll regard the Dewhirst hypothesis in the same light as the Massingham one. Yes, I’ll be annoyed at the book chapters I’ll have to re-write yet again, but I will regret nothing of the journey that left me much smarter than when I started it.

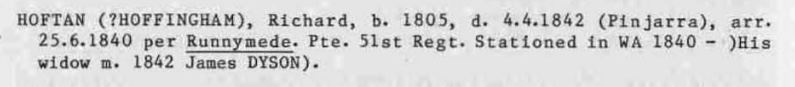

At this precise moment, as with my previous theory, I can neither conclusively prove nor disprove that the widow of a young soldier from Cheshire who was stationed in VDL as a prison guard before sailing to Western Australia, is the first wife of James Dyson either. The Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australia’s claim is not correlated in any documentation I have had access to so far.

To date, my instinct is that this is not James Dyson’s future first wife and I got it right the first second time. My perverse justification for this opinion is that while a number of falsifications on existing documents are needed to accept the Dewhirst/Dyson union as a viable proposition, the prospect of a charge of bigamy is a good an incentive as anything else. On the other hand, no good reason has so far emerged for a widow of Private Richard Hofton (or Hoofton, as his military record sometimes has it) to claim she was a Spinster on her marriage certificate when she was not.

Also when Hofton’s death was recorded in his Regiment’s pay book, the only next-of-kin in line to receive the balance of his salary was his father, also named Richard, thought to be living in Warrington, Cheshire. No mention at all of him being married, which I find suspicious.

I remain prepared to be proven completely, utterly, and majestically wrong about this, and everything else.

P.S.

In the course of the ongoing research into Richard Hofton, I stumbled onto this quite wonderful website concerning the first soldiers based in Western Australia. Unlike a certain highly esteemed reference book, it actually contains references.

Redcoat Settlers in Western Australia 1826-1869

P.P.S.

Expect my book to be delayed by at least another year..

P.P.P.S.

According to wikipedia, the first volume of what became the Bicentennial Dictionary of Western Australia was developed from a card index catalogue developed by the mother of the person who happens to be the one who says on television that Fanny Dyson probably died of puerperal fever. F.F.S.

Leave a Reply