The more things change, the more they stay the same.

There was no doubt he did it.

Geraldton, Western Australia, January 3, 1876: A man had just murdered his spouse. It was his second marriage, they had two young children together and a third was on its way, but they were far from being a happy couple. His business acumen had deserted him and money was tight. He drank a lot now — and they were packing up to move house yet again. He had been drinking that day and they had been arguing yet again. Then he produced the shotgun. He threatened to shoot his wife.

The removal-man took the weapon away from him, telling him him he “was mad.” The gun was hidden in a locked room and his wife was given the key. How scared she was is not entirely clear: earlier she had dismissed the concern of the removalist by saying “Take no notice of him.” It was probably to the relief of everybody when he went out to the pub.

He returned later in the afternoon and the couple engaged in their last childish argument together over the affordability of a pair of child’s shoes. Bridget Mountain was their domestic servant. For most of that day she had been occupied in the kitchen which was slightly separated from the main house across a court yard. About 4 o’clock she heard her mistress cry “Oh! Bridget! the gun! the gun!” The servant girl ran to the kitchen doorway which her mistress was running toward — then a shot rang out.

The sound drew the next door neighbour outside, and caused the master of the nearby government school to look out his window. Both saw the man in the yard with the shotgun raised to his shoulder aiming at the kitchen door. Bridget saw him too and felt the shot particles that hit her in the leg. The wife cried “Bridget, I’m shot! I’m dying!” as she fell through the kitchen doorway. Bridget caught her and closed the kitchen door. What her mistress did next makes sense only if she realised the eldest of her two children was still outside with the husband who had just shot her. One deliberate minute later she opened the kitchen door and stepped back outside. The door slammed shut and then a second shot rang out. Both the schoolmaster and the next door neighbour witnessed the man raise the gun and fire the shot which killed his wife. He aimed for her head, the top of which he blew off. Also watching as her father murdered her mother and unborn sibling was their two-year-old daughter. When the police constable arrived, the man was holding the child in his arms and was seated next to the body of his wife. “I’ve done it.” he stated. After being allowed to whisper something in the ear of the corpse, he was lead away unresisting to the police lockup.

He had been charged on the spot with murdering his wife. That was also the conclusion delivered by the inquest in Geraldton held the very next day. The man was held in custody in the lock-up until he could be shipped down to Perth for his criminal trial which was scheduled to be held in the Supreme Court in Perth three months later. While in custody he admitted to his gaoler:

“I wish to God this had never happened; for the sake of them that’s gone ; but what’s done can’t be undone.”

The Herald (Fremantle, WA : 1867 – 1886) Sat 20 May 1876 Page 3

No common criminal?

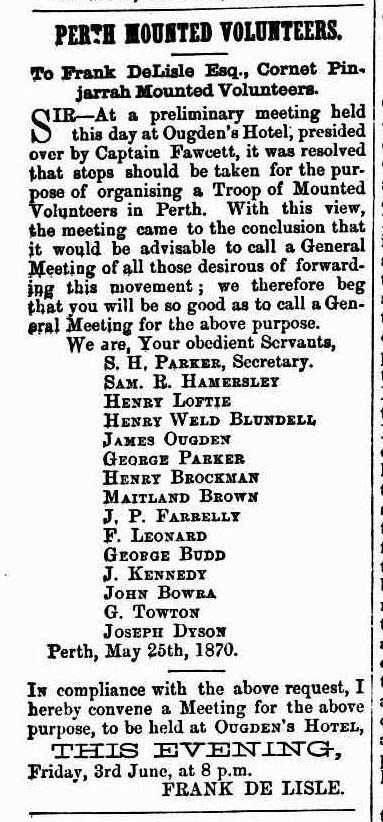

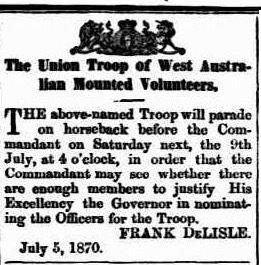

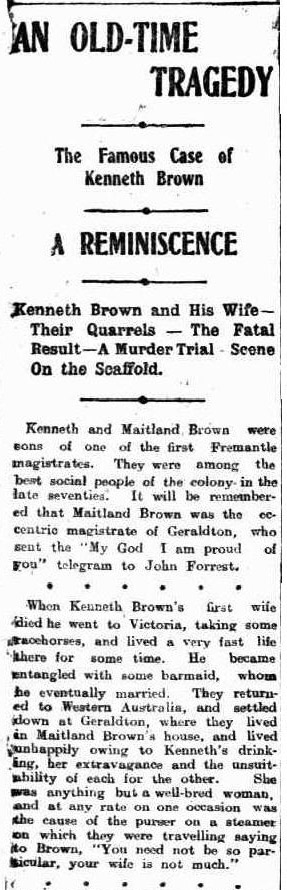

On 10 April 1876, when his first trial began, one thing was never questioned, he had killed his wife in the circumstances described above. But this was a colony where who you were was infinitely more important than the gravity of the crime you had committed. This man belonged to a culture where it was considered an insult to his society for a trained lawyer to mount a defence for an aboriginal prisoner. It had shaken that same society to the core when a white man had recently been found guilty by a magistrate of manslaughter of an aboriginal man and sentenced to a couple of years in gaol (that magistrate was promptly sacked). But the prisoner in the dock was not an aboriginal man, and he had the most expensive legal team a scion of the colonial gentry could afford. Most crucially, the man on trial for his life was called Kenneth Brown and he was the older brother of Maitland — probably the most popular white man in the colony. A verdict of guilty was by no means assured.

Maitland Brown was also a killer — and in open celebration of the blood on his hands he was the undisputed hero to a significant proportion of settlers, particularly the elite property owners of whom he was an exemplar. His reputation was made by the ruthless extermination of a number of aboriginal people he had deliberately gone to their country to destroy. A career in politics beckoned. By 1876 he was virtually a one-man opposition party to the Governor and Government of the day. If responsible government had existed in the colony at the time (ironic, as Brown opposed this system at this stage of his career), he would have been elected unopposed head of that new government. When his brother shot his wife and unborn child to death Maitland was at the apex of his influence. The question was how far was he prepared to leverage his popularity to save his family’s honour (and his brother’s life). The popular perception that Maitland Brown was all powerful in the colony of Western Australia was about to be tested against the reality of that perception.

Among Equals

The legend of Maitland Brown’s omnipotence was very much reinforced by the outcome of the first trial. The jury failed to reach a verdict, a miss-trial was declared when a sole member of the panel refused to go along with the majority’s wish to acquit Kenneth Brown on the grounds of his being of unsound mind. A significant amount of gaming the system had gone into play to engineer this near-win for the defence. The population of Western Australia was still quite tiny, and only a small subset of this population — men with a certain quantity of money or real estate — were eligible to serve on juries. The size of the population was such that everyone in this category would know everyone else — related by family, friendship or business ties. The defence did not leave this to chance — half the names on the roll they objected to, until the only ones left were exactly the subset of the population who would do anything for Maitland Brown, their hero — even pervert the course of justice.

Some of the supposedly confidential deliberations of the jury members were leaked into the public domain during the weeks that followed — and it appears that Maitland Brown’s supporters had overplayed their hand:—

“He was ready to listen to reason [the hold-out juror], but when the leading spirit among the eleven, in a last attempt to convince him said, ‘Don’t think of the prisoner, he is a scoundrel; think of the family.’ He replied, ‘If that is your best argument I have nothing more to say.’”

Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser Fri 30 Jun 1876 Page 4

The names of the twelve jurors are all known, but in the reverse situation of the member of the firing squad randomly given a blank (so as to assuage his conscience that he did not fire the killing shot), the identity of the man with a conscience remains a secret. His name belongs to one of the following: George A. Letch, Dennis Brennan, William Britnall, John D. Manning, James R. Mews, John Allpike, Walter Easton, William Rewell junior, Alfred Minchin, Henry W. McGlew and James Manning. Captain George F. Wilkinson was foreman of the jury as well as being a foundation member of that exclusive Perth club for gentlemen: The Weld Club. Maitland Brown was also a member, as was an unidentifiable member of the second jury who was on record bloviating at the bar or at the billiard tables:

“… He would not agree to a verdict of guilty, whatever might be the evidence…”

Gippsland Times (Vic. : 1861 – 1954) Thu 29 Jun 1876 Page 4

The jury of the second trial comprised Selby J. Spurling (foreman), Thomas Connor, George W. Smith, James Allpike, Thomas Jones, E. W. Haynes, William Coombs, Henry Caphorn, William Smith, Alexander Cumming, Charles Watson and Reginald Hare. It may have been more than just the failure of the previous trial that spurred the prosecution to make their case out more aggressively — In the intervening month, six Fenian political prisoners had broken out of Fremantle Gaol and made good their escape by sea on an American-flagged ship. A colonial vessel hastily commissioned as a gun boat gave chase, but when reality dawned that recapturing the escapees would also start a war between Great Britain and the US, the colonials backed down and the prisoners got away. There might have been a begrudging acceptance before this that the brother of Maitland Brown might be allowed to get away with murder. — but now a second public official humiliation could no longer be stomached.

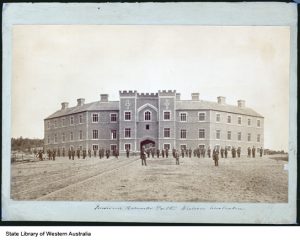

This time the attorney general explained in great detail how the evidence raised could not excuse a murder and called further witnesses attesting to Kenneth Brown’s sanity. The defence likewise upped the ante. They called the aged mother of Kenneth and Maitland to the stand. The palpable embarrassment leaps off the page of the court transcripts as she testified that madness ran in her family and that her own mother allegedly tried to kill someone. Expert witness after expert witness was called to confirm this assertion, even Maitland Brown himself took the stand. In 1876 the Supreme Court occupied a barn-like structure on the same site as the building that replaced it at the beginning of the 20th century. It was formerly the government commissariat for Perth, but where the sacks of corn or gunpowder were once stacked, as many members of the public who could cram the galleries were there to watch their justice system in action. It may be that an increasing number of them did not like what they heard. Maitland Brown, even on the witness stand, was consistent in his guileless honesty (or gobsmacking hubris, if you prefer). He (in rather more words than less) attributed his brother’s mental decline to the fact that he had made a match with someone of significantly lower class than himself. The weekly newspapers covered both trials in minute (to the point of being libellous) detail. That was the contention of the defence who attempted to bring writs of contempt of court against a couple of them. The judge dismissed this action.

After three days of evidence and a careful summing up by the judge, the jury was sent into isolation to consider the verdict. A few more days later and it was clear that this jury was not going to come to an unanimous verdict either. As was the case with the first trial, the defence had made any number of objections against potential jurors who might not have taken to heart that Maitland Brown was their peer as much as his brother was. It was a successful strategy (in the short term) for it bought the defence time. By the end of the sessions the list of suitable jurors on the roll had been exhausted and ordinarily wouldn’t have been regenerated until the next sitting of the court — in another month’s time. But rejecting jurors wholesale who didn’t meet the defence’s criteria of “friendliness” carried with it an increasing risk the more times a conclusive victory eluded them. The same family, friendship or business ties that bound those they had accepted were near identical for those they rejected — those who now realised that the family of Maitland Brown who heretofore they may have admired, or at least been neutral towards, had as good as said they were not to be trusted. Then there were those members of that class Kenneth Brown’s late wife belonged to. Ordinarily, they would not have been called to serve on a jury, but they were present in the gallery in great numbers.

The judge called for a third jury to sit in a trial that would start the same day the old one closed. The defence challenged the remaining dozen men in the juror’s-book and when it was over only ten had passed muster — too few for a trial. It seemed that it was all over for another month. The attorney-general made a suggestion. The Judge concurred. The doors of the courthouse were shut, so as not to allow any of the gallery visitors to escape, and officers of the court also headed outside to sweep the nearby docks. The judge was Sir Archibald Burt, chief justice of the Supreme Court. He may have been a fellow member of the Weld club, drinking along side Maitland Brown and any number of the jurors called to date, but he was also a lawyer, and one thing no member of that profession can ever tolerate is having the piss taken of their office. An ancient ritual called a tales was called.

Telling tales

Two special jurors were sworn in by the court — then in turn, they called members of the public in the courthouse (or just passing outside) to the stand, and questioned them rigorously as to whether they were eligible to be a member of a jury. Each of the tales, both of them, was a miniature trial in its own right, with cross-examinations by the defence, prosecution and the learned judge. By the end of the process the full jury compliment of twelve were empanelled. They were Rice Saunders (foreman), Michael Benson junior, James Green; Harry Williams, Frederick Tondout; John Urquhart, Sydney Chester, Francis Armstrong junior, Frederick Platt and Alexander Halliday; with John Summers and James Snowball the two dragged in off the street.

The evidence of the third trial was a carbon-copy of the second. The conclusion of the jury was not. Kenneth Brown was found guilty of wilful murder by unanimous decision. He was promptly sentenced to death.

Twelve days later behind the walls of the Perth Gaol, Kenneth Brown was hanged. His brother Maitland stood by him on the scaffold while he died. From the moment of the “guilty” verdict onwards, legend supplanted fact as far as the fate of Kenneth Brown was concerned. Such was the influence Maitland Brown was supposed to exert that the prison guard was doubled around the gaol in the days up to the execution lest the wardens could be simply bribed to let their prisoner go. Maitland himself was only supposed to have been allowed to see his brother before the end on giving his personal word of honour to the Governor (of the Colony of Western Australia, not the governor of the gaol) that he would not aid his brother’s escape. Even so, long after the body of Kenneth Brown had been returned to his family for a private inhumation, the story arose (and was believed to be true by even Kenneth Brown’s own descendants) that he escaped the gallows with his brother’s help, and made his way to America, much as the Irish political prisoners had so recently successfully done.

In reality, Maitland Brown’s fortune had been largely spent by the time of the conviction on exorbitant legal bills accrued by the defence. Politically, he was now damaged goods and he resigned his place on the Legislative Council after the third trial. He would return to politics in future years, but he was no longer the universal hero of the colony he once had been. He never stood for office once responsible government was introduced a decade-and-a-half later. The affair publicly revealed the fault lines in Western Australian colonial society that had been baked into it since it creation nearly half-a century ago, but maybe this was something that could only be discussed openly in a neighbouring colony —

“[…]‘trial by jury was on its trial in this colony.’ It is almost impossible for any one who has not resided here to understand how the small population of this place is united and connected by relationships or by mutual interests, how little public feeling there is, and how greatly private feelings or interests guide the actions of people in matters great and small. The country wants new blood and increased commerce with the outer world, from which it has been so long excluded […]”

The Argus, Tue 27 Jun 1876 Page 7

However, in the Fremantle Herald, a local paper despised by the local elites for if no other reason than it was founded and written by expired convicts (the very bottom of the heap) felt confident enough to editorialise —

“Public feeling, which in the first instance was quiet, was roused by the challenging of the jury and the extravagance of the defence; […]”

The Herald, Sat 17 Jun 1876 Page 2

Crime and retribution

One member of the public so roused, was so indignant that the legal system of his home town was being subverted, made his opinion known to the world at large, and if the following memoir of him can be believed, influenced the court on the course of action that they followed in the third trial —

“Dyson pere it was who was so insistent, during the trial for wilful murder of the scion of a celebrated W.A. family, that some of the first and second juries which had disagreed had been got at, that when a third trial was about to commence the judge suddenly issued an order to police and warders to go out into the public street, preferably down towards the waterside, and bring in a dozen working men in their shirt sleeves for choice to act as a jury. This was done and the accused man was promptly found guilty deservedly and executed.”

Sunday Times, Sunday 24 April 1927, page 14

This Dyson pere is, of course, James Dyson, until recently Perth City Councillor and still an elected member of the Perth Road Board. There is no contemporary evidence of him ventilating his opinion at this time, but seriously — knowing what is known about his character, what were the chances of him remaining silent if his temper was riled? And James Dyson had cause to have the judicial system fresh on his mind. His son had just been gaoled for theft. Andrew “Drewy” Dyson had a somewhat unique vantage point to observe what subsequently unfolded while he served six months hard labour in Old Perth Gaol. Drewy might not have heard his father speak publicly on the subject — but he might have heard Maitland Brown and the defence team discussing his father… If James Dyson had so publicly set himself against the family of Maitland Brown and his influential friends what then were the consequences?

One year later, first Dyson’s Corner then Dyson’s Swamp, the bedrocks of his family’s economic security, went up for sale. James failed to be re-elected to the Perth Road Board, thus ending his civic career. His marriage failed and the husband of one of his daughters repudiated their marriage. He was forced to move into the residence of his eldest son Joseph.

Fifty years or more after the trial and execution of Kenneth Brown, the tale of Dyson’s alleged influence on the proceedings was published. It came to light during reminiscences on the occasion of death of James’ most famous son Drewy. The Sunday Times article is uncharacteristically coy about the identity of “the scion of a celebrated W.A. family” who his late father helped send to the gallows. Something else was going on at about the same time.

A child of Kenneth Brown, a daughter from his first marriage to the daughter of the Colonial Chaplain, Frederick Wittenoom, was attempting to run for the WA parliament for a second term. She was not successful in that year, 1927, nor would ever succeed again. If the coded message of her family’s shame in Drewy’s obituary was a bit of political gaming and did influence the vote in anyway, it would be the second time a Dyson had interfered with the political fortunes of this influential family. Edith Dircksey Cowan (nee Brown)’s place in Australian and Western Australian history was assured in any case. She was the first woman elected to any parliament in the Commonwealth. She has a university named after her and her face is on the Australian $50 note. She was also a founder (in 1926) of the Royal Western Australian Historical Society.

Is it any wonder the Dysons were effectively wiped from the living memory of Australian history?