Not quite a love story yet.

This is the tale of two convicts in Van Diemen’s Land. Their story does not have an end yet: happy, sad or otherwise. Can you help?

The man

Lorenzo Johnstone was an Irishman born around the year 1808. His complexion was brown and his face deeply pitted with the scars of acne or maybe smallpox. A labourer from the village of Muckney in County Monaghan, he may have very soon realised he had made a terrible mistake joining the British Army.

The 1st Regiment of Foot was stationed in Ireland until about the time Johnstone turned seventeen. Then the Regiment was split in two, and the 1st Battalion of the regiment to which Johnstone was attached transferred to Scotland. His first Court Martial for desertion took place on 20 November 1829 in Fort George, Inverness. He served 25 days in the stockade for that infraction. The question that must be raised is whether Johnstone was trying to get back home to Ireland, or he was in dread of returning there — the Regiment was scheduled to return to Ireland in 1833.

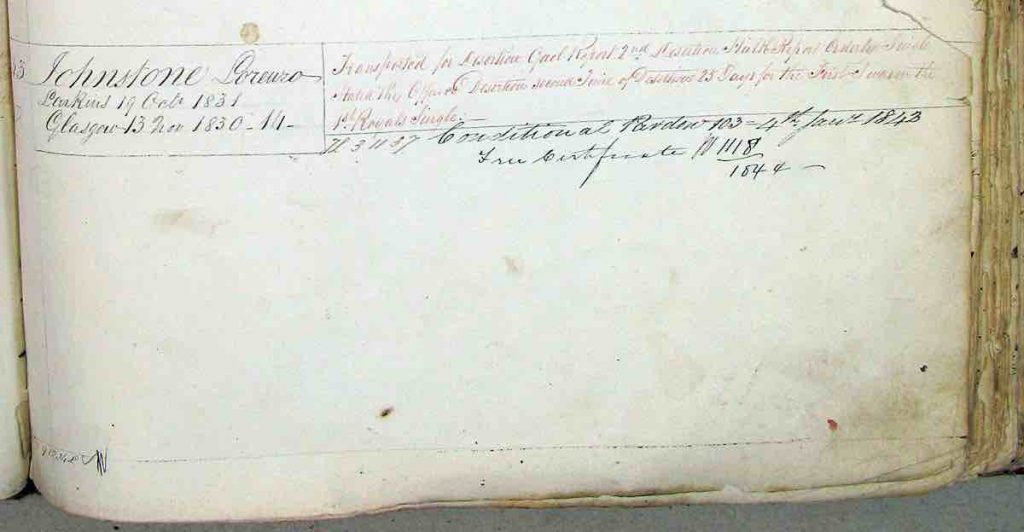

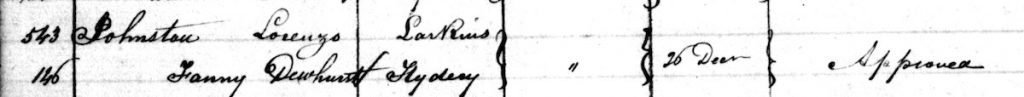

If his hope was to return to Ireland, that wish was to be fulfilled — albeit briefly. One year nearly to to day after he first absconded, His second Court Martial for desertion took place at Glasgow on the 13 November 1830. He was sentenced to fourteen years transportation. His convict ship Larkins, sailed from Downs, Ireland on 11 June 1831, and arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on 19 October. His military career was most certainly over and he seemed destined never to see Ireland or Scotland ever again.

Johnstone is one of those infuriating oddities — an Australian convict with a completely clean conduct record during his sentence. By May 1832, he was most certainly in Launceston (or its environs), for that is where a fellow felon, Thomas Quarrie, was convicted for nicking some of his clothes (to the value of four shillings). He was assigned to someone in the Launceston district on 9 December 1834.

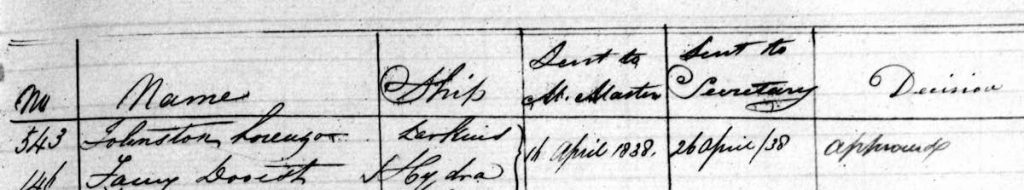

On 3 November 1837, at about the midway point of his sentence, he was granted his ticket-of-leave. This effectively paroled him to work for whoever he chose, or work on his own account. He could even be an employer, or take on apprentices. There were however, stringent restrictions on his movements, who he could associate with, or how late he could be out at night. But Lorenzo Johnstone remained resolutely on the right side of the law. So it was on 11 April 1838 that he submitted his application to the relevant authority for permission to marry. Within two weeks the reply was made via correspondence with the Colonial Secretary in Hobart. Permission was duly granted. Johnstone should have been a very happy man — He owned outright — or at the very least had unencumbered use of — a horse and cart, so he may have felt secure in providing a service that should always be in demand—transporting things from one place to another. He was thirty years old. Maybe for the first time in his life he felt that everything was moving in the right direction. If so it was a sentiment his bride-to-be may not have shared. The wedding date was delayed, and delayed again…

The woman

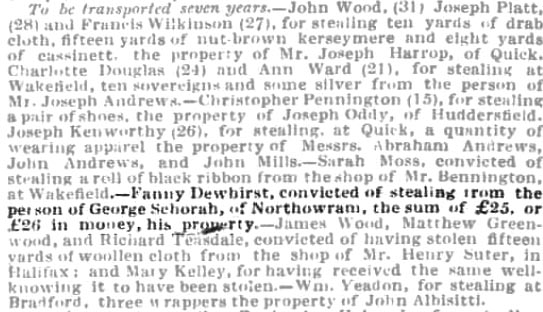

Fanny Dewhirst claimed (or it was estimated) that she was born about the year 1813 — however if her parents were William and Mary Dewhirst and she was baptised in Heptonstall, near Halifax in Yorkshire on 28 August 1808, she was several years older than that. It might be a modern sensibility to hope that the later is true, for if it was the former, she was barely 16 when it was recorded that she was “on the town” a euphemism for having no home or protection, or more commonly — supporting herself by prostitution. At some stage before her arrest in 1832, she lost her right eye.

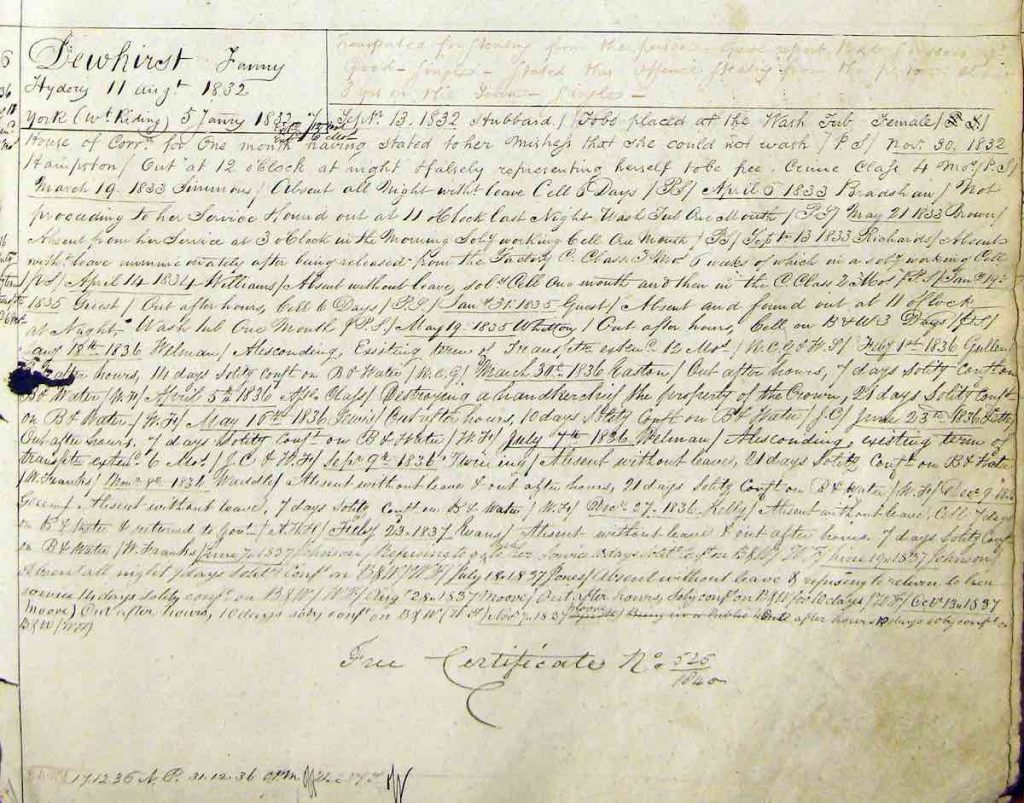

On a winter’s day 5 January 1832 she was sentenced to seven year’s transportation for the theft of a very large sum of money from a man publicly identified as a Mr George Schorah of Northowram (a location a mile or so north-east of Hallifax town centre). £25-£26 was a vast sum of money for the time, and the sentence handed down at the West Riding Christmas General Quarter Sessions in Wakefield seems almost lenient until it is understood that Mr Schorah was most certainly also Fanny’s customer and the chairman of the court was a Reverend. Fanny Dewhirst was imprisoned at York Castle until March when she was transported down south to Woolwich, near London, then cross country west to Plymouth in Devon, where she would board her transport vessel to Van Diemen’s Land. The convict barque Hydery departed England on 11 April 1832 and arrived in Hobart Town on 10 August 1832. Within a month she was sent north to Launceston, and assigned to work as a domestic servant for someone named Hubbard. On 13 September 1832 her extensive bad conduct record gained its first entry.

She refused to do the laundry as ordered to by her mistress, so Fanny began the long relationship with the house of correction for female prisoners back south in Hobart Town — at the Cascades Female Factory where she served a month at the wash tub. It was the first of many sentences for a multitude of infractions of the rules. These included:— [being] out after curfew and falsely representing herself to be free; Absent all night without leave; Absent from her service at 3 o’clock in the morning; Absconding; Destroying a handkerchief (property of the crown); Refusing to go back to her service; Being in public (out after hours)… etc. This is only a small sampling of the cause of her subsequent punishments. “Being out after hours” is by far the most common offence for which she was charged (16 times) but “being absent without leave” (12 times) comes a close second. There were more than a few occasions when she could be found guilty of both at the same time. The usual punishment was solitary confinement on bread and water. It has been calculated that she spent 176 days (nearly six months) this way.

One of her masters was Major Wellman of the 57th Regiment. He was stationed in Launceston and was assigned lands at Norfolk Plains (both locations associated with Fanny Dewhirst). Whoever he was, she must have detested this soldier or his family with a passion, for two times during 1836 when assigned to him she ran away. For the crime of absconding, her sentence of transportation was increased by eighteen-months.

On 17 November 1837 she was sentenced to ten days of solitary confinement on bread and water for being out in public after hours. She was employed by someone called Moore who resided Launceston. This was the third time she had received the same sentence for the same crime while in Moore’s service. It was to be the last offence she was charged with for the remainder of her time as a transportee, now due to expire in July 1840. Then on 11 April 1838, Lorenzo Johnstone applied for leave to marry her. The government had no objections, but did she?

Fanny Dewhirst could neither read or write. Those life skills she had acquired she had learnt the hard painful way. According to the conventional morality of the day she was supposed to just curl up and die when her situation failed to match the expectations of those who made the rules. If her life in Van Diemen’s Land and her life before that in Yorkshire suggests any thing it was that this was a person who would fight passionately to survive in the moment, regardless of the long term consequences. If survival was a moment by moment affair, then so would be pleasure. If she lived by the minute then Lorenzo Johnstone gave every indication of being someone who played a long game in life. A soldier’s life had taught him discipline, but she had already run away from one soldier. Did she really want to spent the remainder of her life with another?

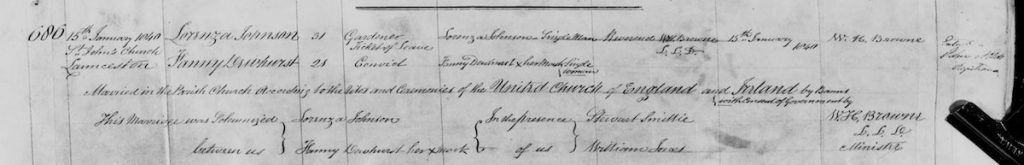

Something strange happened on 28 November 1839. Lorenzo Johnstone applied a second time to marry Miss Fanny Dewhirst. Why he needed to apply to the authorities again is not remotely clear. Maybe too much time had elapsed between the first permission and the wedding ceremony? Once again, the Lieutenant-Governor initialled assent to the lawful and permanent union of the two convicts, which was communicated back to the parties on 26 December 1839. On 15 January 1840, Lorenzo Johnstone, aged 31, was married to Fanny, who gave her age as 21 (pull the other one), according to the rites of the Church of England in the Launceston parish church of St John. Lorenzo listed his trade as a gardener, but he would not have owned his own farm. He could not legally own land — yet.

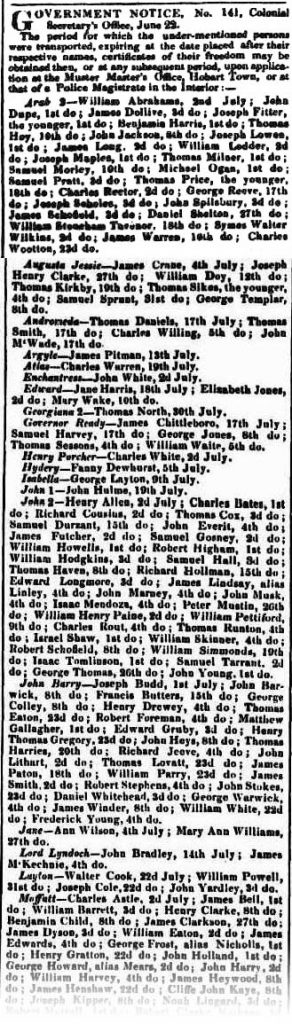

For Mrs Lorenzo Johnstone, there was one final hurdle to overcome before her past as Fanny Dewhirst was definitively behind her. The moment came six months after her marriage on 5 July 1840 when she granted her Certificate of Freedom. She was free by virtue of servitude — She had served every hour, every day, every month, of her eight and a half year sentence. Now she was utterly free to go where she wanted to, live the life she chose. It would be a fair guess she hated Van Diemen’s Land and would want to get away from that island as soon as she was able to. But of course, she wasn’t free. She was married to Lorenzo Johnstone and he was still a Ticket-of-Leave convict. He had four years left of his sentence to serve. Here was the bitter irony — She had never conformed to the rules — she had flouted them at every opportunity (and paid the price). She was never granted a Ticket of Leave, much less a Conditional Pardon which was the next reward for good behaviour — yet even with an extension to her sentence by eighteen months, she now had more legal rights than her husband — who had started his sentence three years before hers — had a spotless good behaviour record, but could not legally leave the Launceston district.

In the circumstances, it reads like a cruel joke that Lorenzo Johnstone’s conditional pardon mooted as early as January 1842 but not valid “until Her Majesty’s pleasure be known” was finally promulgated on 31 August 1843, for the following cause:—

“Having served ten years in the Colony without a charge of misconduct”

On 30 November 1842 Johnstone had been fined by a magistrate for a trivial cart-riding offence. Maybe that had been enough to delay his Conditional Pardon? He received his Certificate of Freedom by servitude in 1844. Now he could own land or leave the Colony anytime he chose — or was able to. In previous eras expired convicts were granted free land to work, but those days were long past. But had he time left to save his marriage?

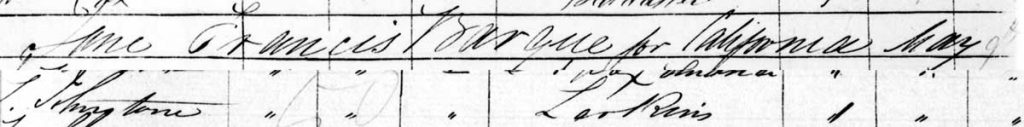

It took six more years before he finally departed from Van Diemen’s Land. Gold had been found across the Pacific Ocean in California, USA, back in 1848, and on 9 May 1850 he sailed from Launceston on the Jane Francis bound for San Francisco. Being who he was, he dotted all the “i”s and crossed all the “t”s on the paperwork. This is how we can be fairly certain that his wife, Fanny Johnstone did not sail with him on that vessel. This is the last verified record of Lorenzo Johnstone and (in the negative) his wife. There are any number of unverified sightings. Here lies the point of danger in concluding this story…

In Pennsylvania USA, in the year 1995, a man named Lorenzo Johnston was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. After seventeen years behind bars he was freed by a higher court on the grounds that he had been falsely convicted due to insufficient evidence. Four months later, yet another court sent him back to prison to resume his original sentence. As of today (April 2019) Lorenzo Johnson was a free man living with his family in New York. He spent twenty-two years of his life behind bars for a crime he most certainly did not commit.

Now it should be fairly self-evident that Lorenzo Johnson and Lorenzo Johnstone are not the same person (Nor is it slightly feasible that one could be the great-great-great-great grandparent of the other). The stakes for me in a theory I have about the fate of the nineteenth-century individual after his wife’s freedom was granted in 1840 are immeasurably lower than that of a man wrongly convicted of a capital offence on circumstantial evidence and prejudice against him for the colour of his skin. I’m not going to state my theory here (though it shouldn’t be too hard to work out my line of reasoning from other articles on this site) because the case of Lorenzo Johnson — the one who had the misfortune to be in the wrong place at the wrong time and not be a pitted-faced Irishman — should be a warning about leaping to conclusions without being in possession of all the facts, or any proof at all. At the moment, all I have are coincidences — as did the jurors at Johnson’s first trial. The result was a gross miscarriage of justice.

The dilemma…

Herein lies my problem: I have a theory about this couple. However I cannot prove my theory, but I cannot conclusively disprove it either. Conclusive facts that would disprove my case would be records of husband and wife together after the year 1840, or records of Mrs Fanny Johnstone after that date living a life away from her spouse. There is some evidence in Tasmania that the latter is what might have occurred.

Unfortunately Johnstone and its variants Johnson or Johnston are all too common as family names. Lorenzo Johnstone (the Irishman) was recorded as being capable of being able to read and write, so while others might have misspelled his name (and did) we can be reasonably certain that Johnstone is the variant that he prefered. There are records of a Fanny Johnstone having involvements with the law in Launceston between the years 1863 and 1871, However in only the earliest instance was she actually found guilty of something (fined 6 shillings for disturbing the peace with one Thomas Crawford) (In the last recorded, she was employed as a sick-nurse for the family of a police constable). The difficulty is that there were other families of Johnstones in that town during the era, and of that subset of the population were a number of other women named Fanny — both of the Mrs and Miss variety. I cannot prove the Fanny Johnstone I wish to trace is one of the above — nor can I disprove it yet. There is no death or burial record that I can identify for Fanny Johnstone that plausibly fits the former Miss Dewhirst, nor can I find evidence that supports her remarriage.

As for Lorenzo Johnstone, his movements after 1850 are similarly hard to interpret:—

- In October 1852 a Mr Lorenzo Johnson [sic] aged 37, sailed from the colony of Victoria to Launceston on a vessel called the Launceston…

- But a Mr L. Johnson [sic] and wife sailed from San Francisco to Port Jackson, New South Wales on the vessel Abyssinia in the year 1853…

- In 1876 an occupant of the Victorian goldfields named Lorenzo Johnson [sic] died, but according to his death record he was only a young man of 25 years. If this is correct, he was born sometime about the year 1851. The names of his parents are unrecorded and no record of his birth has yet been found.

… So the fate of Lorenzo Johnstone remains as uncertain as that of his wife and for much the same reason.

In Summary

Can you help? Are you a researcher or even a descendant of Lorenzo Johnstone (or Johnson) born Muckney, County Monaghan, Ireland about the year 1808, or Fanny Dewhirst (or Dewhurst) born Halifax, the West Riding of Yorkshire, England about the year 1813 (or as early as 1808)?

If you have come across stories concerning either of these two convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, or are connected to either by ties of family, I would love to hear from you and complete their story. If you know Lorenzo and Fanny are your ancestors or you wish to claim them as your own, please make that claim. That is what I would be doing… if I had the evidence.

References

Convict records for Lorenzo Johnstone at Libraries Tasmania

Convict records for Fanny Dewhirst at Libraries Tasmania

Fanny Dewhirst’s convict record has been completely transcribed by the Female Convicts Research Centre. Registration is required to view these transcriptions, but I can’t overstate how useful access to this database has been. https://www.femaleconvicts.org.au/

Leave a Reply