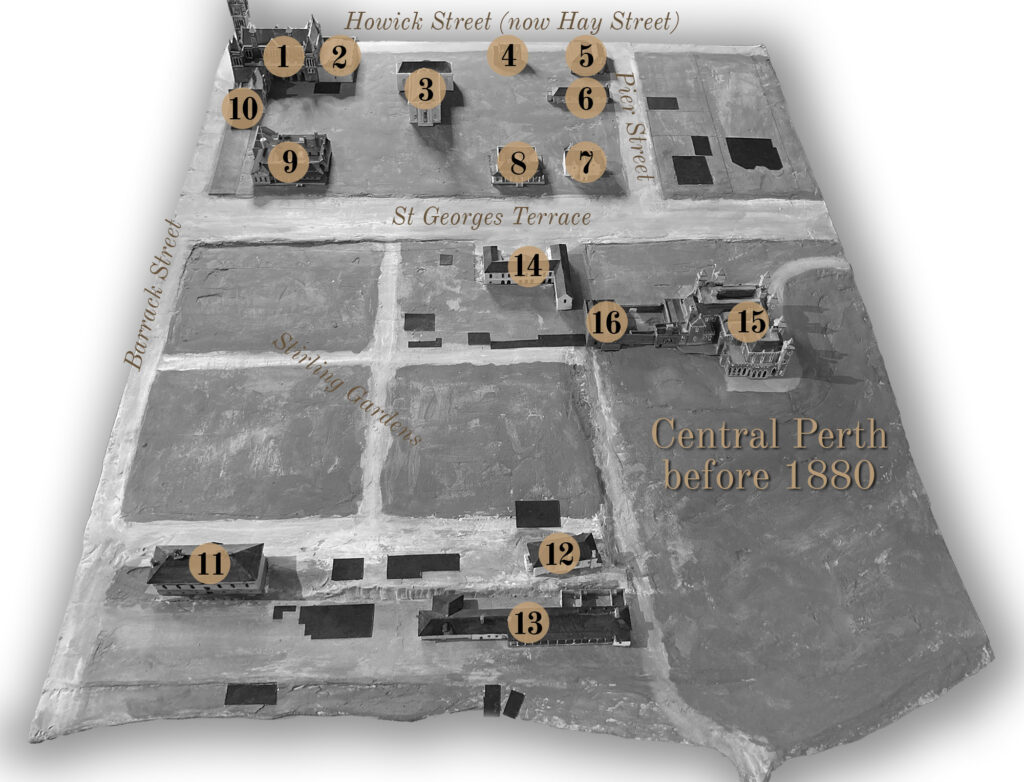

A guide to the diorama of central Perth before 1880 on display in the Museum of Perth

This was the administrative heart of the colonial settlement. Some of the oldest surviving structures in the city are located on this diorama which you might recognise today.

- Perth Town Hall

- Legislative Council

- The Original St George’s Church

- Freemason’s Hall

- Swan Mechanic’s Institute

- School House

- The Deanery

- Officer’s Barracks

- Soldier’s Barracks

- The Guard/Pump House

- Commissariat Stores

- The Old Court House

- Water Police Barracks/ Perth Lock-up

- Government Offices

- New Government House

- Old Government Ball Room

- The black shapes represent other buildings remaining to be added to this representation of pre-gold rush era Perth.

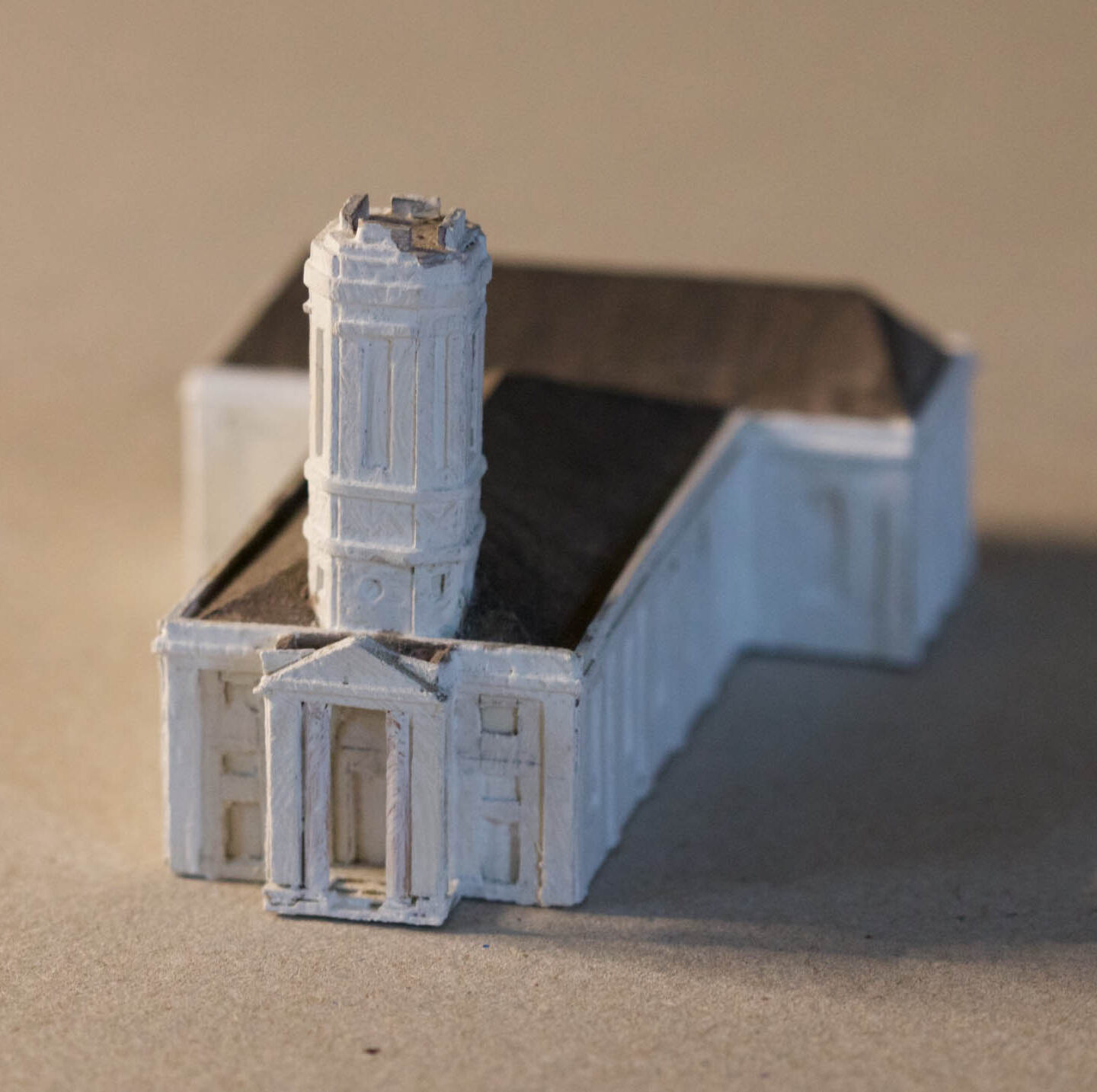

1. Perth Town Hall

Started 1867, opened 1870, and still here today!

A civic centre for the capital of Western Australia was merely an afterthought by Governor Hampton after he had spent most of the imperial funds vested in him to develop the colony, instead blown most of it to finish a flashy new home for himself. A new Town Hall was his farewell gift to his subjects. The citizens of Perth would have no say in any of the design and construction process, all that was required of them was to be obsequiously grateful that they were granted his magnanimous condescension at all.

The foundation stone was laid near the corner of Barrack Street and Howick Street (Now an extension of Hay Street) in the year 1867. Only after the handover to the Perth City Council in 1870 were all the aspects of the ornate design that were not properly thought through, laid bare.

The most potentially lethal flaw was the single wooden staircase that was the only way up and out of the great hall above the arches of the undercroft. If a fire had ever broken out, hundreds would have been crushed in the stampede to escape. If the fire came from the stairwell every single person in the upper storey would have died. Such a catastrophe arround that time and place might even have ended the colonial experiment right then.

Governor Robinson, Hampton’s successor, pointed this out after attending one of the first functions held in the hall after it was opened. So, amongst the first modifications to to the original design were the addition of further stairwells located in the otherwise ornamental turrets at the corners of the hall.

Soon after that it was realised that no public lavatories at all had been provided for use in this new centre of the town’s life.

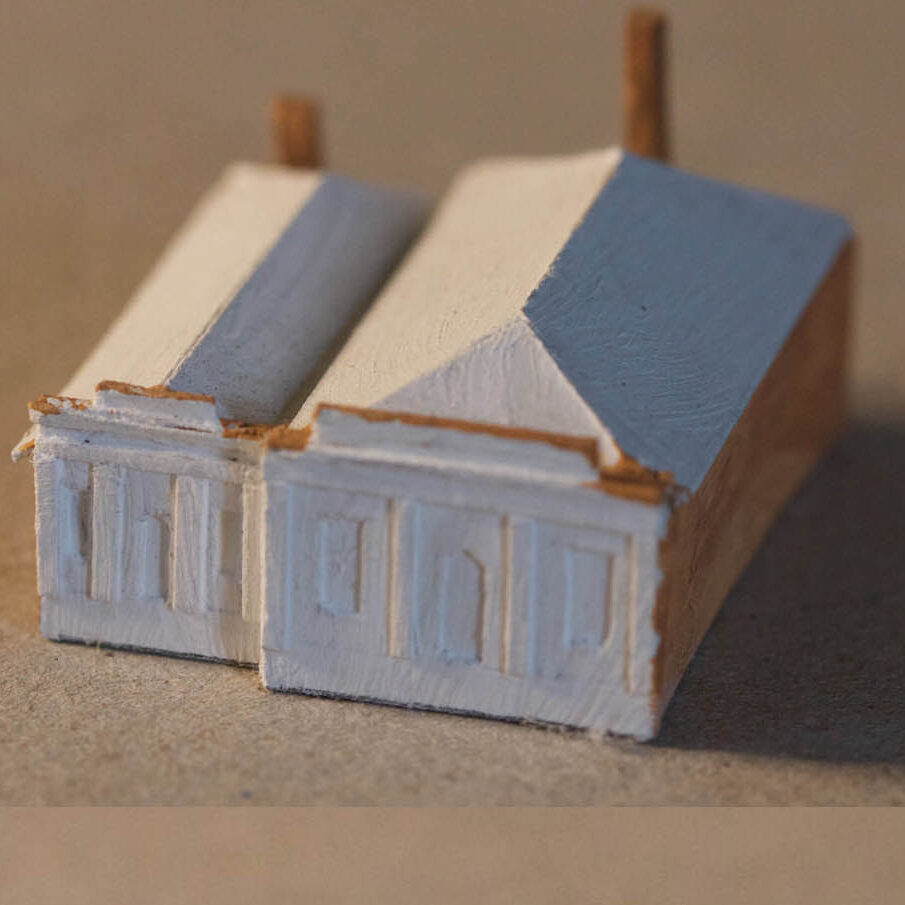

2. The Legislative Council building.

Started 1867, opened 1870, demolished 1968

If the Town Hall itself was an afterthought by a former ruler of the colony, this small hall attached to it was a last minute addition to the plan to house the “gift” of incoming Governor Robinson’s grant of limited representational government. The new Legislative Council chamber was ready for use when the first few elected members took their seats to find they had no ability to influence events. The Governor retained, by and large, the option to rule as an autocrat, whether he chose to exercise that power or not.

It was not until 1890 when responsible government was granted (and the dictatorial powers of a premier supplanted those of a governor), that the Legislative Council moved down the road into the old 1837 Government office building on St George’s Terrace while the new second chamber of the Legislative Assembly replaced them in to the Howick Street chamber. After the two branches of the legislature were reunited up on Harvest Terrace after 1904, the redundant chamber was sometimes repurposed as a government bank, but was finally demolished in 1968, only two years shy of the centenary of its construction.

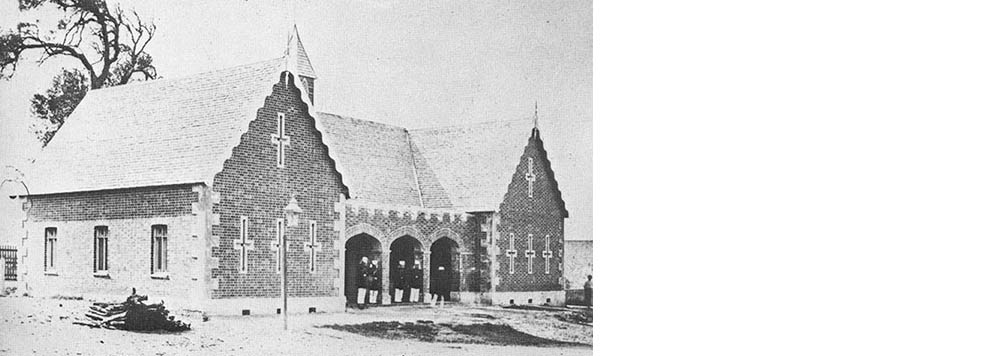

3. St George’s church.

Started 1841, completed 1845, demolished c. 1890s

When what became St Georges Terrace was first surveyed out in 1829, it was listed on the map as King George Street. Then King George IV dropped dead a year later, and there was no reason left to pretend anyone had liked him. The words “King” and “Street” were discreetly erased and substituted by “Saint” and “Terrace” instead. When the adherents of the Church of England finally got sick of time sharing their existing place of worship with local court cases and school classes, the proposed St George’s Church was named after the street it overlooked, rather than the patron saint of ye olde England.

After three years of fund raising, the ruling class of Perth had raised just enough for a foundation stone to be laid in 1841. But by then the alternative Wesleyan Methodist sect had long ago opened their first chapel in town and laid the foundation stone for a second later that same year. It was possibly not now the best of times for the Colonial Chaplain Wittenoom to have a brain-snap and denounce his co-religionists as schismatics and dissenters.

Not only had many prominent Wesleyans donated to the Anglican church building fund (just as many Anglicans had contributed to the first Methodist shed), they also counted a disproportionately high proportion of the town’s sawyers and carpenters within their comparatively tiny congregation. Maybe it was not that that much of a coincidence that the church builders’ budget flew out the windows they could no longer afford to build when all the sawyers of the town colluded to suddenly raise their prices.

The barn-like St George’s Church was eventually completed in 1845. It took another three years for the bishop of the local diocese to make it over west from Adelaide to actually consecrate the place for worship.

Perth was next informed during 1856 that their very small town was henceforth a cathedral city. Part of that newfound status involved rebranding the church as Cathedral. A rectangular extension was tacked on to the north end of the structure a few years later to form its final, awkwardly proportioned, T-shape profile.

The writing was on the wall metaphorically if not literally for the old St George’s Cathedral from the late 1870’s onwards when work on a replacement began immediately to it’s east. After a decade of construction work, the two structures existed side by side for a short time until the old church was torn down during the early 1890’s

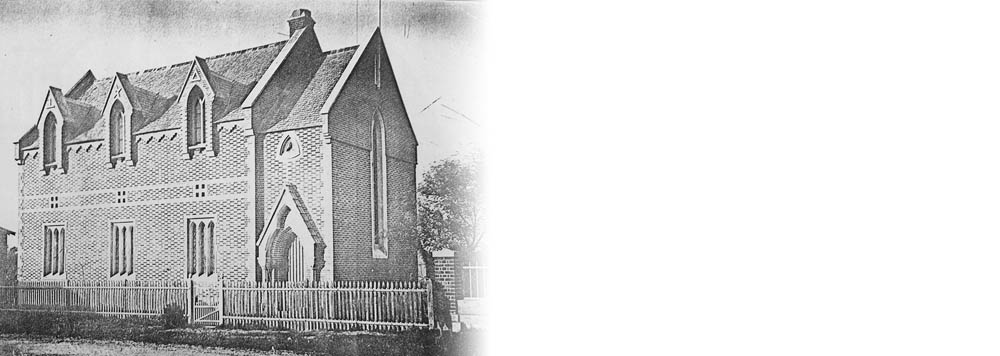

4. The Freemason’s Hall.

Built c. 1866, demolished 1970s.

After their first club house was erected on Howick Street in about 1866, the lodge members of the Freemasons no longer had to fraternise in public houses along side to common hoi poli in such locations, as say — “The Freemason’s Arms”? Their club house was later extended, but this is the earliest iteration. The lodge members moved to a different location entirely during the 1890s, so their old hall was reused by various government departments, the R&I bank, and finally the Public Trustee Office before it was knocked down in the 1970s.

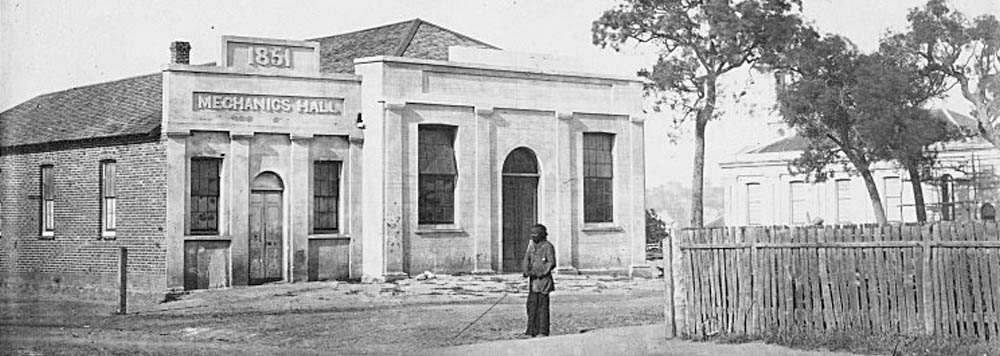

5. Swan Mechanics Institute.

Built 1853, demolished 1897.

The oldest part of this structure, located on the corner of Howick and Pier Street, was constructed in 1853 — The 1851 sign on the frontage denoted the year the society that operated out of this building was formed. Further wings were constructed westwards until room on the block ran out, by then it consisted of hall space, meeting rooms, a lending library and a display of curiosities that was the origin of the WA museum’s collection. This was also where the council for the City of Perth held their meetings before the construction of the Town Hall. It was one of the few spaces outside a liquor vending establishment or a private home where a quiet meeting could take place on somewhere other than government property.

Re-branded as the Perth Literary Institute, the original buildings were entirely replaced in 1897 to make way for a far grander structure that also failed to survive until the 21st century.

6. Government School.

Built 1854, demolished after 1930.

This was erected about the same time, or only a couple of years after, the Old Boy’s School was built away down on St Georges Terrace in 1854. This was the classroom for the girls. Somewhat less money and effort was spent on this school building, although the ventilation was certainly better that the earlier effort. At some indeterminate date it stopped being used as a school and was occupied by a government department related to the land and surveys office. The government lithographic office reproduced maps, plans and other printed documents as needed. After a government print works was finally set up across town, the site was leased or sold for the strangest change of use yet. Before it was torn down sometime after 1930, this was the disreputable location of Perth’s public bath house.

7. The Deanery.

Built 1859, still standing!

Formerly on this site stood the original Perth lock-up. It was not for long-term prisoners — they were sent to the Round House in Fremantle. However, in a moment of official panic, the first quasi-judicial execution in the colony took place on this spot.

When the lock-up was moved down to the waterfront into the newly built Water Police Complex, and the Army moved away from the original barracks next door, this site of evil memory was marked for a touch of 19th century gentrification. On this spot, a genteel residence for the churchman who was to look after the newly upgraded Cathedral was constructed, complete with gardens and trellises hung with grapes surrounded by a picket fence.

8. Officer’s Barracks.

Erected early 1830’s, demolished 1917.

There were two barrack buildings that made up the British Army establishment that gave nearby Barrack Street it’s name. One was for the regular soldiers, the other housed their commanding officers. They were both completed very early in the Swan River Colony’s history, with the Officer’s barracks at least, in use by 1834.

Both barracks were roughly of a similar layout and covered about the same surface area. Obviously there would be considerably more comfort for one group than the other as there were many more regular soldiers (with their wives and children) than there were of the men who commanded them to fit into one of those spaces. Obviously enough, the officers of the Swan River Colony were always going to get the better deal of it.

However, when Governor Sir James Stirling returned to his capital in 1834 after a two year absence, he compared the rude shack he would otherwise be returning to, with the solid Officer’s barracks constructed by architect Henry Revelley during his absence. Quite where his officers had to bivouac while the Governor appropriated their gaff until his new house was completed, is not spelt out in the records. RHIP – Rank Has It’s Privileges.

After the British army were replaced by pensioner-soldiers during the convict era, the fine officer’s barracks structure was repurposed as a police station. After a local Worthy’s son died on a distant battlefield during 1917, his grieving father decided to salve his loss by having what should be the earliest surviving colonial landmark in the city replaced by a murky grey red brick hall.

9. Soldier’s Barracks

Erected early 1930’s, demolished late 1880’s

No architectural plans or photographs exist of the totality of the structure where the regular rank and file were housed in Perth before the early 1850s. Only a pencil sketch dating to 1841 and some other distant depictions of the barracks within the town from across the water on Mt Eliza suggest that its initial layout was very close to that for the officers. What is clear is that the soldier’s barracks were both expanded and remodelled over the years as, up to the time it became the nucleus for the latest expansion of government offices during the 1880s. For at least two decades before that date, the former military establishment was entirely obscured from the view of the street by densely planted trees. Only a field canon pointed across the road towards Stirling Square provided any clue as to what lay behind foliage.

A ground plan of the complex does survive from the early 1860s. It does show the expansion of the original form to cover all the ground on the site. What these extensions looked like remain mostly in the realm of educated guesses. One of the more researchable of the features that may or may not ever have been constructed were the fives courts. This was a handball game similar to squash played in special designed three-sided ball courts. The game is still played in certain elite British Public (i.e: private) schools.

The end of the soldier’s barracks came as the old structure was slowly surrounded by the two storey (later increased to 3) office block erected on the west side in the late 1870s. A second wing of this new office block was later built on the east side. When the two wings were connected, the last traces of the old barracks vanished underneath the new colonial General Post Office. Today this new structure is better known as the Old Treasury Buildings.

10. The Guard House.

Built c. 1855, demolished c. 1910s

Also known as the Pump House, and later modified to include a court room for the Police magistrate to do his work, the Guard House was erected about the same time as the pensioner barracks on the west end of the ‘Terrace and in a similar corporate style. Neither were part of the original British army complex that gave Barrack Street its name.

It’s possible the pumping house part of this building’s design was one of the reasons the decision was taken to house Perth’s first fire fighting appliance in the understory of the Town Hall immediately next door from 1878 — but this is just idle speculation.

At some date during the early 20th century the Guard House was replaced by a nondescript two storey structure that did service as the Government Tourist Bureau, until it was in turn replaced by an anonymous concrete box (also since demolished). An anonymous glass box now occupies the site. It does, however, contain a court house once again.

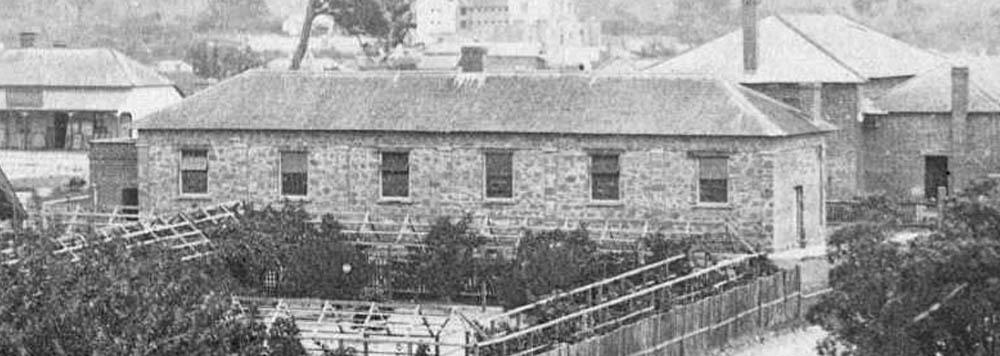

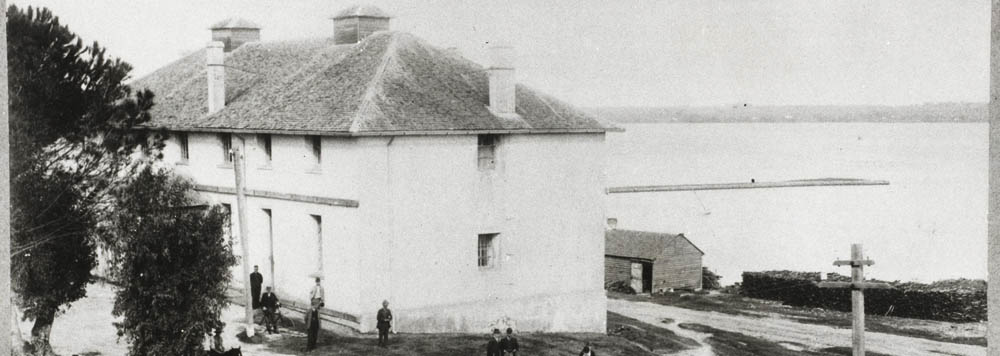

11. Commissariat Stores

Built 1837, demolished by 1902

The British army’s supply depot or Commissariat was was once all that stood between the settlers, one bad harvest, and starvation. It was built close to the water front, near the Barrack Street jetty, for easy transit of stores. After this three storey warehouse was no longer required for its original purpose after the last British regiments were removed from the colony, it saw out the remainder of its lifetime as the Supreme Court building for the colony.

By the end of the 19th Century the former Commissariat Stores lay marooned far inland from the reclaimed shore line. It was then replaced by the vast new Supreme court complex still on the site.

12. The Old Courthouse

Built 1837. The oldest surviving European structure in Perth city.

It was built to be used as a public hall, court house, school room, and Anglican place of worship. While there is marginally more space within than appears from without, The Old Courthouse is known as the Old Courthouse because that was the last original purpose it was still used for. Today it is a law museum.

Look at the strange alignment of the Old Court House on the diorama. The model has not been bumped out of place by accident. The foundations for this building must have gone down in 1835 before the re-alignment of the street plan for the town was completed by the survey department.

13. Water Police Barracks/Lock Up.

Built c 1850, demolished by 1902.

Beneath the limestone cliff underneath the Old Court House was a long complex of buildings the made up the residence of the Water Police. From it’s erection soon after the dawn of the convict era in 1850 to it’s demolition beneath the edifice of the 1902 Supreme Court building, for most of that time it was the centre for law enforcement duties across much of the city. The lock-up cells saw far more business that those at the Perth Gaol on the other side of town. The only holding cells specifically for women were located here. Among the other buildings about the place lay boat sheds, stables, and store rooms.

14. Government Offices

Built 1837, demolished 1861.

The city of Perth has been home to many office buildings, but this was the the first constructed by the Government as part of a suite of new architecture that included a court house, church and school room (all one building) and the commissariat store. This was where the post office, survey department, and Records office (among other functions) were going to be housed.

The structure was too small almost the moment it was completed and a wing was immediately extended out one side of the rear to form a lopsided Y shaped structure down the side of the slope towards the river front. What made the design so interesting was the way different levels evolved as the building extended. One side was a maze of walkways and stairs. It looked great, but was hell to work in. After “responsible” government arrived in 1890, the Legislative Council moved in to these old offices. The building was then reprieved for a few decades more when the recommendations of a royal commission to build a unified Parliament house on the spot was over-ridden in favour of a site on Harvest Terrace.

It was eventually flattened in 1961 in favour of the current Council House.

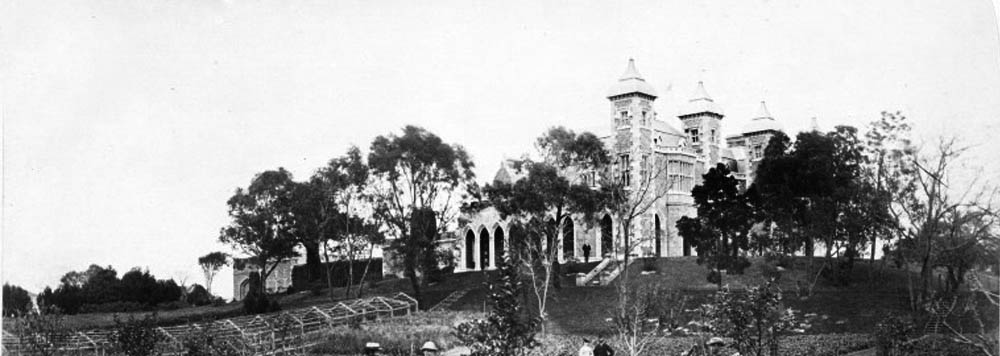

15. New Government House.

Built 1857, still here.

In the opinion of the Governors who ruled Western Australia during the height of the convict era, the sarcastic observer who described the old Government house built for Stirling by Revelley as resembling more a lunatic asylum that the residence of a head-of-state— was entirely on the money. Speaking of money, Governors Kennedy and Hampton both had a lot of it courtesy of the revenue from the Imperial Government for the maintenance of the Convict establishment. They could have invested those funds in roads and bridges, or removing the impediment to navigation on the Swan River. Instead they blew most of it on a grand new gaff for themselves. Kennedy started the work in 1859. Hampton arrived as construction was nearly completed, decided he didn’t like what had been done and ordered hugely expensive alterations so work was not complete until 1863. Maybe it was as a sop to his more observant critics that he “gifted” his city a new Town Hall as a present.

16. The Old Government Ballroom/Banqueting Hall.

Built by 1867, replaced 1890’s.

This was a modest appendage to the New Government House. It lay half in the Governor’s domain, and half in the Government domain- to make a distinction between the two. The public entrance to the ball room lay on the public side of the border, so the Governor need never have to tolerate undesirables turning up his driveway. The Old Ball Room was eventually replaced by a monstrously scaled New Government Ball Room. By this date in the late 19th Century, the power of the monarch’s representative in this colony, now a state, was much diminished.

Leave a Reply