Family history research led me to hunt for the Sharp family, who were then just one name among many. The count of direct ancestors you possess increases exponentially each generation the further back you go. By the time of your third great-grand parents (GGG grandmother or father), that could be up to thirty-two different family names. Double that number each subsequent generation.

John Sharpe died at his home, “Barvin”, Leviathan Reef, on the outskirts of the town of Maryborough in Victoria, on 17th July 1904 at the age of seventy nine. His body travelled by train to the cemetery in the east of Melbourne where it was buried. He had arrived in Port Philip Bay, Australia, on a ship called the Hibernia, 11 October 1852. Sometime after he arrived in Australia, he added an “e” to the end of his name, presumably just to frustrate future family history researchers. His story in the Australian colonies is still to be properly told. However his daughter, Tamar, left one of the few tangible traces of the Sharp(e) family’s existence for me in the form of her signature on a nineteenth century petition in Victoria calling for women’s suffrage. As she is a direct ancestor, this is an object of very great pride to me.

But it was the location of the family’s origins that attracted my attention. They came from England (as a disproportionate number of my ancestors do), but the Sharps was the first I had discovered who came from Cumberland, an English county on the north eastern border with Scotland. I had visited the region many years ago during my first visit to Britain in 1998. I visited Carlisle, the principal city of the region, and I remembered standing on the walls of the castle, a bleak edifice of red brick, looking across equally bleak country rolling away to the north.

This was both a working castle and a fortress city. Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned here, and the bloody conclusion of the Jacobite rebellion after unification of the two nations, resolved itself here in a pile of gory entrails. I was staring across the land from where the invading Scots army, not once but many times would have emerged. It was still a dozen years before I learnt that it would be perfectly feasible that I might have ancestors both doing the running and screaming with faces blue from woad paint (or the extreme cold), AND also standing on the battlements, voiding their loins in pure abject terror.

When I finally found out something about my ancestry I discovered that once again, I has passed very near a location without understanding any of it’s personal significance to me. John Sharp was born at a place called Cardurnock, a few miles west of Carlisle on the shores of the Solway firth, some time before 15 April 1827, which was the date of his baptism. Why one thing interests me and not another is something I don’t entirely understand within myself yet, but it was learning that John’s father, a farmer named William Sharp, had, after his eldest son had departed for Australia, taken out the lease of a water-powered flour mill in a nearby parish called Allhallows and ended his days at a place called Harby Brow. The more I learned from the English Census records, the more I wanted to see this place.

In October 2015 I finally got the chance. Also to visit the Lakes District, located just south of where the Sharp family had lived. My timing was unusually good. Two months later much of Cumbria, as the historic counties of Cumberland and Westmoreland are now known, were under water from catastrophic winter floods.

From both church and census records, the Sharps seemed to have been farmers or farm labourers in this region since at least the early eighteenth century. I am not surprised I am not able to trace the records any further back, for that was the time when the last lot of invading armies swept through the vicinity and the written records would have made very good kindling. Long part of England’s north western frontier, Cumbria was once with the kingdom of Scotland, and before there was even a concept of England or a Scotland, an independent Celtic kingdom. During the Roman occupation period this was border country — a transition zone between the Mediterranean influenced south and the tribal Picts to the north. Hadrian’s Wall began here, and crawled east, dividing the British island in to two.

The first fort on Wall’s west-most flank was started in a military settlement in what is now the village of Bowness-On-Solway. I caught a bus there from Carlisle. On this flat marshy coast on south side of the Solway firth, a wide flat body of water beyond which which is Scotland, it is not hard to guess where the stones of Hadrian’s Wall ended up. The parish church of St Michael was reputed to be located on the Roman Fort’s granary.

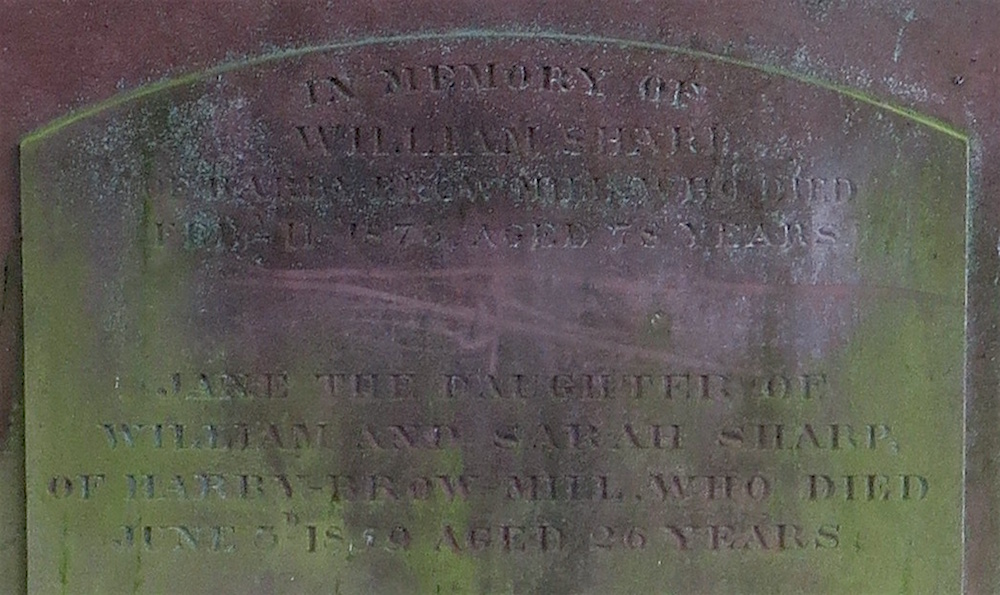

This eight-hundred plus year old building, constructed out of the remains of a eighteen-hundred year old structure, also housed a stone of a more recent date, a mere one-hundred-and-sixty odd years old. The sun was in the wrong direction,

and I could scarcely make out the inscription on the old worn grave stones. It was only when I got back to Australia and was able to enhance the photographs I took that late afternoon, that I found I had been standing before a memorial to Edward and Jane Sharp, parents to William, grandparents to John. They were still alive when he departed for Australia. How close had he been to them? What had it meant to them that now he was gone never to return?

They also farmed at Cardurnock, to the west of Bowness-on-Solway. I tried to walk to there but the hour of the last bus back to my accommodation in Carlisle defeated me. I did, however, get to experience what the surrounding land felt like.

It was stark flat, beautiful country, still farmed today for dairy cattle, also a wildlife reserve, and a place of natural beauty. I believe the British government want to erect a Nuclear Power plant on the site. In Scotland across the water, I could see the decommissioned bulk of an older nuclear plant amid a sea of wind turbines.

Harby Brow is south west of Carlisle, half way to Keswick in the famous Lakes District. It is roughly due south of Bowness-on-Solway. William Sharp and his family did not take possession of the mill until some years after his eldest son John departed for Australia. I wish I knew on what terms they parted. William was born in Cardurnock, but farmed and raised his family in a nearby hamlet called Blitterlees. I did not visit Blitterlees as I have no record of which property they may have occupied in the region. Passing nearby in the bus, it all seemed very similar to the flat country around Cardurnock. Allhallows, the parish where Harby Brow mill was located, was in somewhat different country. It was hilly, but not mountainous. There were dense thickets of trees amid the ploughed fields and tall and thick undergrowth straddled the public right of way along which I walked from the village of Mealsgate to where I hoped my destination would lie.

On my way along, I passed a tiny and ancient stone church, all but strangled by the vegetation, the odd gravestone extending from the foliage like the grin of a gap-toothed hag. I paused, took a photo, and moved on. I passed modern farmsteads on the hilltops, contemporary operations on an ancient template. Avenues of trees lead me to the head of a freshly ploughed meadow across from which I finally saw my destination. This was the manor of Harby Brow, and I knew nearby, had to be the mill.

The manor farm was mostly a nineteenth century collection of buildings that the heritage report rather sniffily states “are of no interest.“ (Sorry, but I beg to differ.) The whole reason that this site has a heritage report at all is due to the pele tower that is attached to one corner of the complex. A pele tower is sort of a mini-castle you have when you don’t have a full-on castle such as they have back in Carlisle. In the millennia after Hadrian’s Wall, such a structure was essential as a place of safety against the constant low-level warfare that jagged to and fro across the uncomfortably nearby border. Soon I would learn that the field I was about to tramp across, legend said, was the site of the very last border raid from Scotland into England, and a battle had taken place on this spot. I would very much like to find some corroborating evidence for this. Also, back in the ancient period, a Roman military camp was sited near here, to guard the river crossing that which Harby Brow would centuries later control, and provided the power for the Mill, now just a short distance away.

Crossing the battle field (as I have christened it) I encountered the farmer whose land it was, and after apologizing for trespassing (for I had veered off the path of the right-of-way) and explaining what I was looking for he pointed me in the right direction.

I stood outside the Harby Brow manor with it’s splendid tower, then walked down the short laneway to the Mill. I knocked on the door but there was nobody home. When I had searched on the internet a few years ago I had learnt that the mill had been renovated as holiday accommodation, but that web site has since vanished so I can only assume it is once again a private family home. It has long since ceased to be a mill. I took a quick look around the side to see where the water wheel was once fixed and departed, not feeling comfortable being a trespasser.

When I returned to the top of the lane between the Mill and the Manor, I met with that farmer again, who not unreasonably, was checking to see this stranger was not getting up to no good. We talked for a while, and perhaps after I had convinced him of my genuineness, he opened up and started to tell me the area’s history — that is how I learned of the last battle and of the Roman fort. It was obvious he loved his home and its heritage and he told me how they had restored as much as they could of the ancient church of Allhalows, the one I had passed earlier. Then he dropped a bombshell. When I mentioned my family name from this area, he told me he remembered seeing that name on a headstone in the overgrown church yard.

I retraced my steps. I walked though the arch into the church yard. Weeds towered over the creeper-strangled stones. The ruins that surrounded it mocked the stout locked wooden door of the restored portion of church. I was resigned to the fact that the knowledge that my forebears had been here and were still remembered would be the extent of the memory I would take away from this place. Then I found it.

Moss green, and dappled in the filtered light of the overhanging branches of a great tree, it stood in splendid isolation and near perfect condition. It stood where it had been since 1876, the tomb stone of my great-great-great-great grandfather William Sharp, the Miller, marking a plot he shared with his daughter Sarah, who died aged only twenty six, who waited in the earth to be reunited with her father for nearly twenty years more.

I stood before them both and contemplated the tangled web of luck, coincidence and unlooked for kindness that had brought me from nearly the other side of the planet, to here, where one tiny sliver of my identity was formed.

Postscript

In February 2017 I visited eastern Australia and was finally able to visit the grave of John Sharpe himself in Melbourne. On visiting the town of Maryborough, some tantalising clues as to his life in Australia presented themselves and I hope to some day write an account of his story as well.