I’ve been wading through the history of the Swamp lately. That is — the actual swamp that had Dyson’s name on it — not the metaphorical entity that represents the Dyson family’s life in early colonial Australia. This is the one that is currently known as Lake Jualbup.

Dyson’s Swamp was always Jualbup. Jualbup has sometimes been Dyson’s Swamp. Jualbup was, is, and always will be Whadjuk Noongar boodjar.

Truth be told, everyone’s favourite former Vandemonian convict in Western Australia was not in direct possession of the swamp that bore his name for very long. He wasn’t even the first settler to claim ownership of it — colonial style.

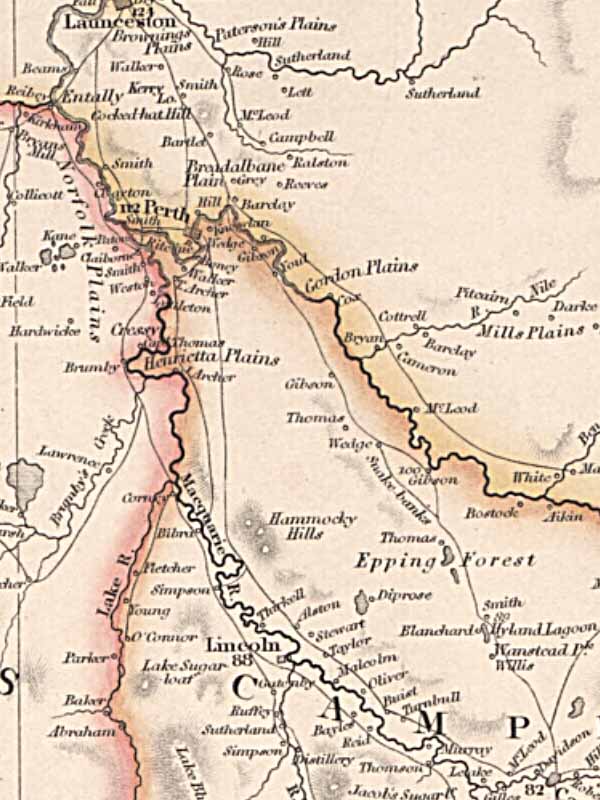

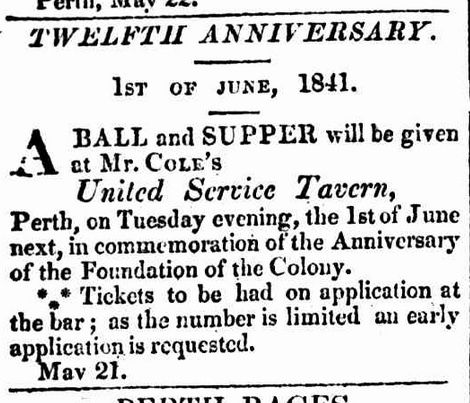

According to Geoffrey Dean in One controversy after another: A chronological history of Lake Jualbup (2011), an agreement to transfer ownership of the swamp from the merchant and chemist George Shenton to James Dyson was first drawn up in the year 1858. The deal was not finalised for another thirteen years — not until the year 1871.

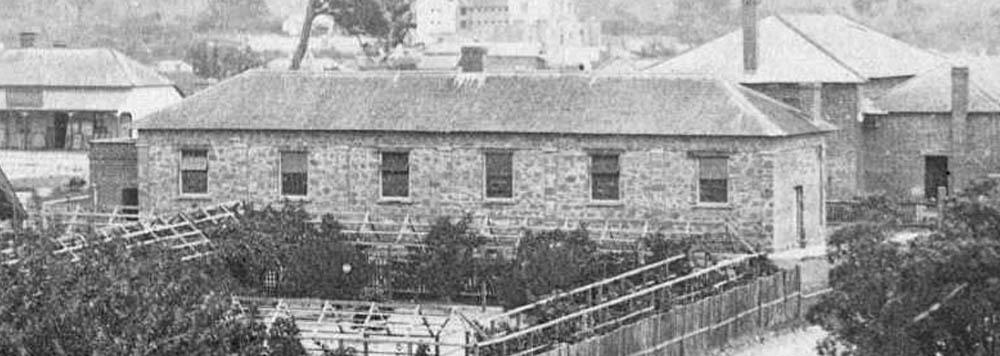

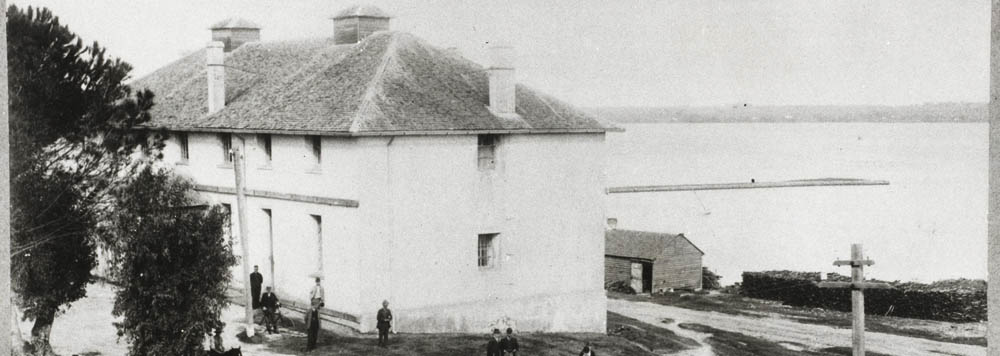

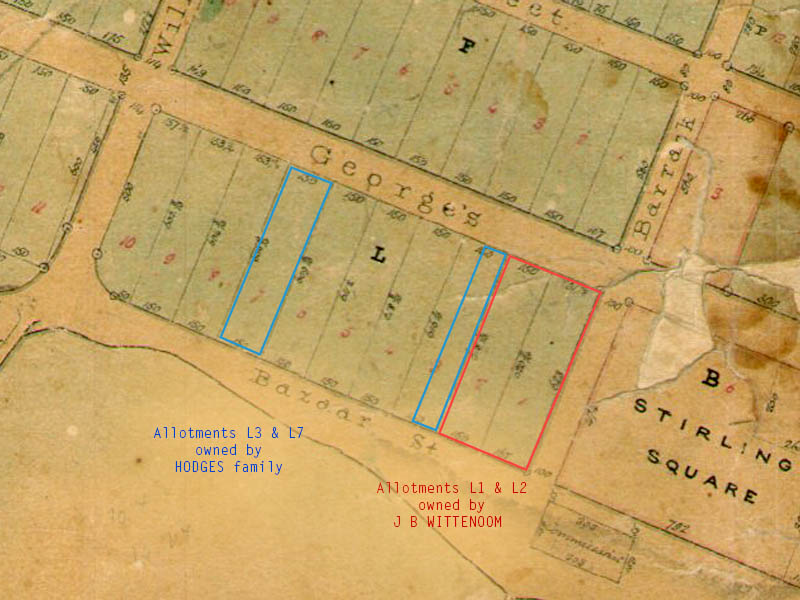

State Records Office WA 1897

As late as 1965, there were still some visible traces of the Swamp as it existed from Dyson’s time. Observe the lone post in the water on the left hand side of the photograph below — this would have been part of the three-rail fence that marked the boundaries between Locations 119 and 118 — the formal designation of Dyson’s Swamp on the title deeds.

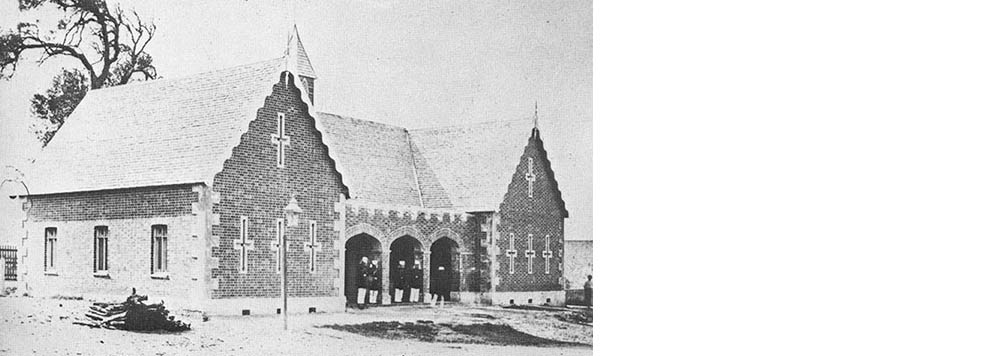

Photograph by Grace Roper

State Library of Western Australia

Dyson’s name was only attached to the title deed for six short years. The Shenton family reclaimed it after 1877. However, until the suburb of Shenton Park swallowed up the bush surrounding the water in the early 20th century, those who actually lived by Jualbup (both Whadjuk and European) carried on their lives as much as before.

The independent timber cutters and cow herders leasing their paddocks and huts from whoever demanded rent from them that month, included identities such as—

JAMES MCKENZIE, who described himself as a gatherer of gum and bark, was charged with being drunk on the premises of Mr. Caesar, of the Emerald Isle hotel. The constable who arrested him said he looked like ‘a wild man,’ who had never in his life been introduced to soap and water, much less a razor or a comb. The prisoner himself did no deny the charge, but submitted that there were extenuating circumstances, which the Court might take into consideration. He said he lived in the gay neighborhood of Dyson’s Swamp, and, not being used to indulge in alcoholic beverages, a few glasses of beer had overpowered him. …

“FREMANTLE POLICE COURT.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 2 February 1885: 3. Web. 7 Oct 2024 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2994801.

He had a neighbour out by the Swamp by the name of

James Thompson (no relation).

James Thompson (no relation) had a hut and a paddock somewhere near the swamp during the years 1879 and 1880. He may have been in the district long before (or after) that, but because he did not report a brown pony or a bundle of firewood to the police as stolen in any other year, he remains effectively anonymous.

(The sons of Kain proved to be innocent of this particular misdeed. Apropos to nothing, they were the sons of a pensioner guardsman who came to Western Australia with the first convict ship, the Scindian in June 1850.)

Thompson (no relation), might be the same James Thompson (also no relation) who also worked for Dyson back in 1852, before the latter could even have dreamed of owning a swamp of his own.

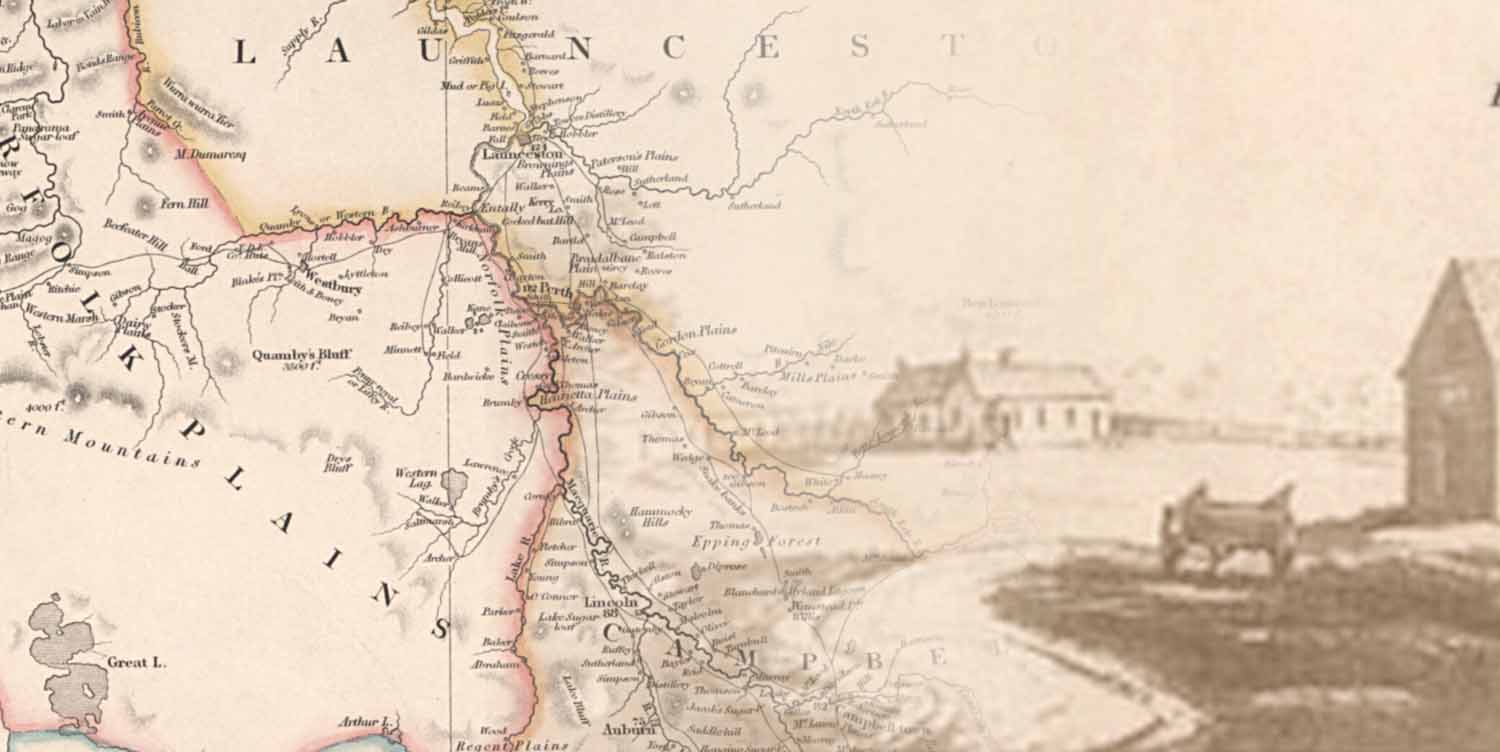

James Thompson, Convict number 1184, arrived in Fremantle on 30 January 1852 per the Marion, the sixth convict transport to be sent to Western Australia. He had already served four years of a ten year sentence for burglarising a house in Coventry, England, so he was granted a ticket-of-leave the day after his arrival.

Dyson employed him from 30 August 1852 for seven months until the beginning of November that same year. It is only guesswork that Thompson (no relation) was one of Dyson’s pitsawyers, or if he had been employed back then anywhere close to his master’s future swamp.

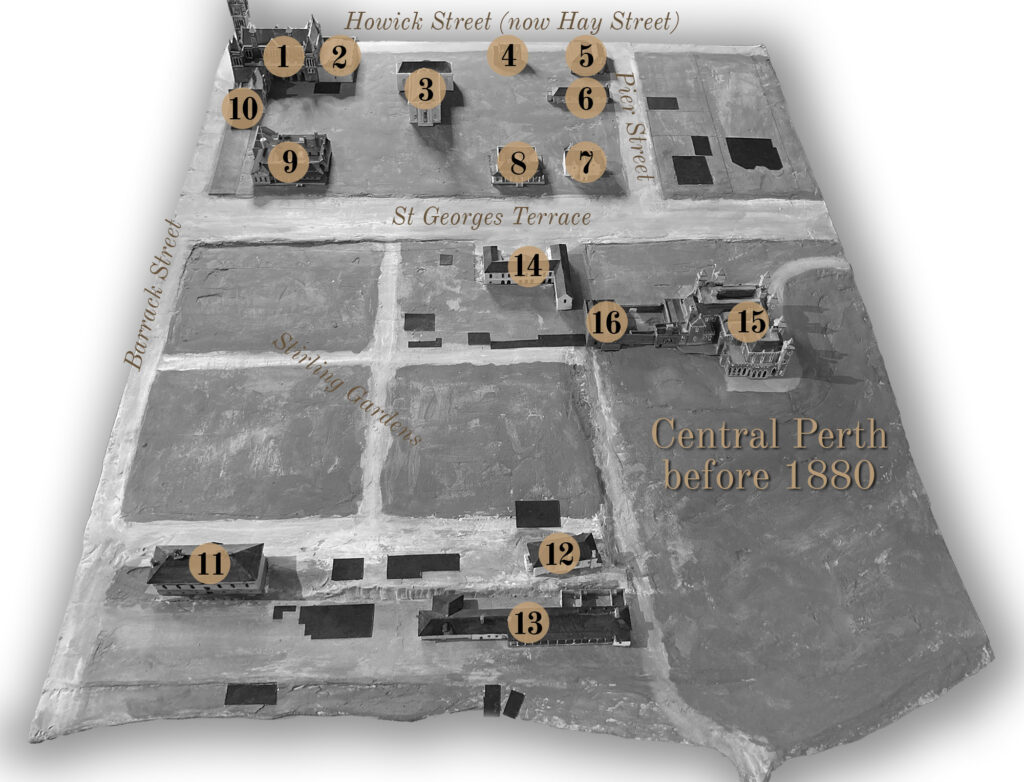

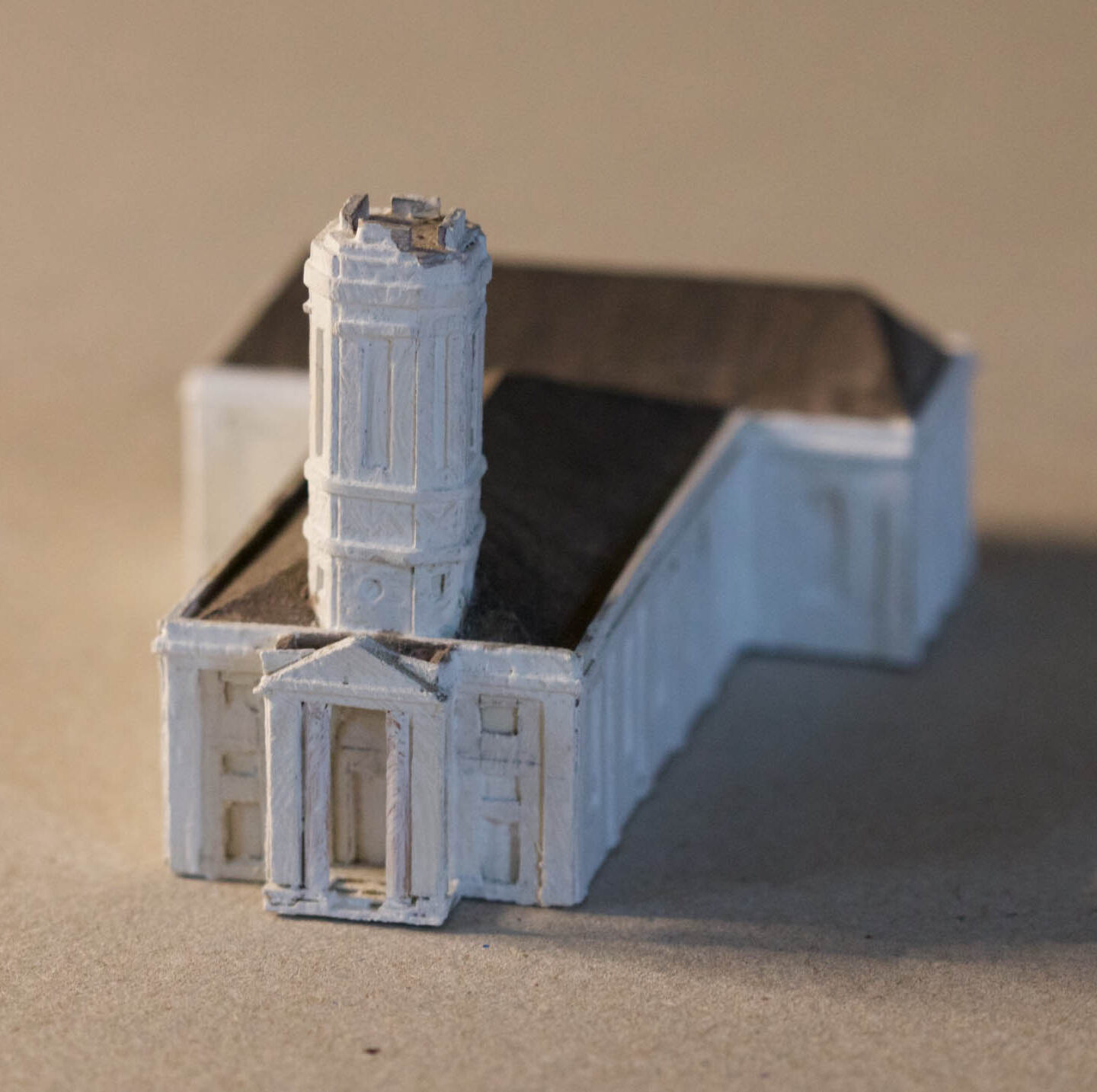

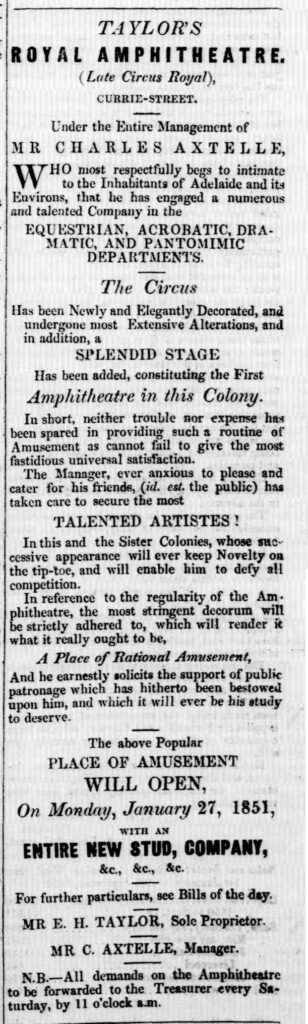

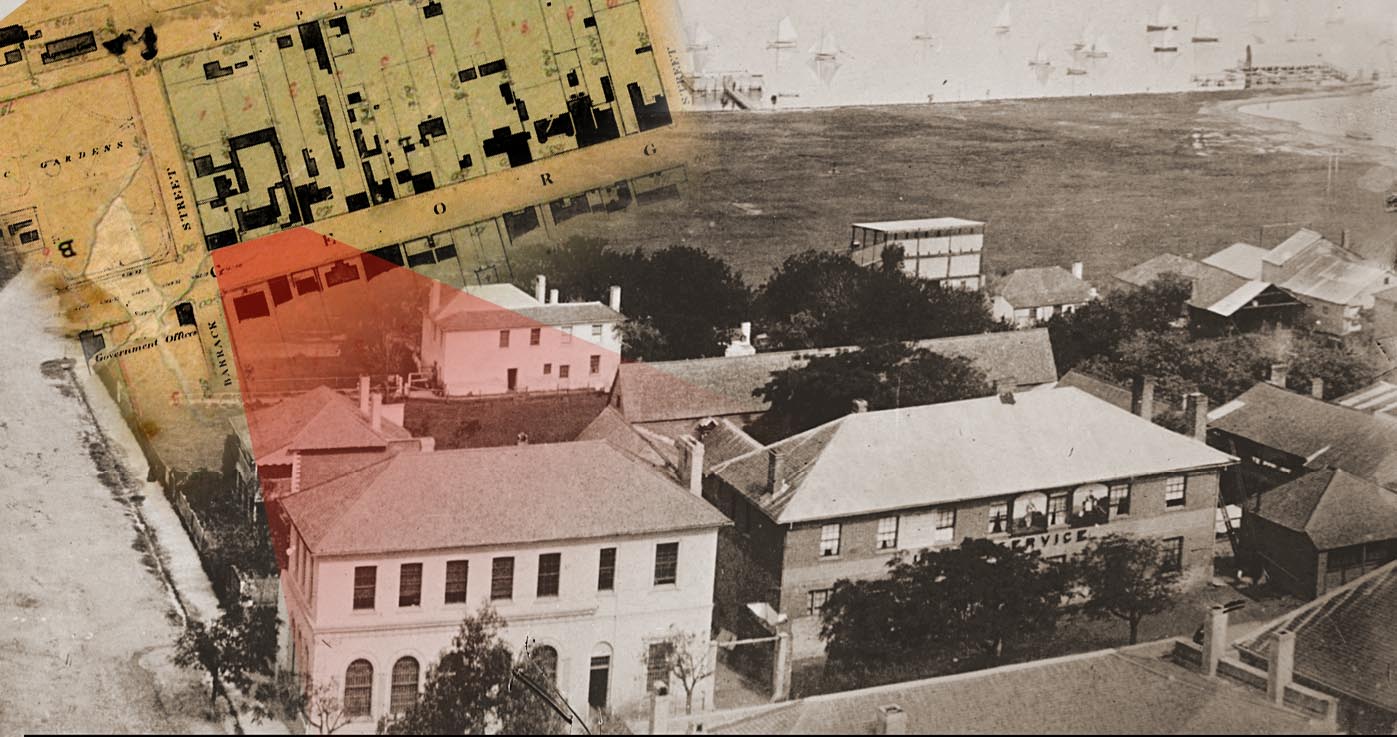

At the time, Dyson had a contract to supply timber for the new colonial hospital down the other end of Murray Street (then Howick Street). Dyson was then living on the corner of King and Murray streets on the other side of town. His marriage had just disintegrated and his first wife had herself committed to the local lunatic asylum.

Against this backdrop, when Thompson finished his time with Dyson in November, he next worked for a baker named Joseph Freeman. His new employer was also a ticket-of-leave convict, but one permitted to run his own business. The address of that business just happened to be nearly next door to the Dyson family home on King Street in Perth.

By 1855 both Thompson (no relation) and Freeman had their conditional pardons, so they were both free to leave Western Australia … almost.

£5 REWARD.

“Advertising” Inquirer (Perth, WA : 1840 – 1855) 12 July 1854: 1. Web. 1 Oct 2024 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65742300.

WHEREAS some anonymous writer has, within the last few days, sent letters to the several Storekeepers of Perth, setting forth that I, Joseph Freeman, Baker, of Dalton’s Terrace, Perth, was about surreptitiously to leave the colony for Melbourne, which slander has had a tendency to do me some degree of harm; I hereby offer the above reward of five pounds to any person who shall render such authentic information as will unmask the cowardly informant with a view to his prosecution; and I here also give notice, that all persons indebted to me, do forthwith settle their accounts; and to request that all persons to whom I may be indebted may furnish to me their accounts on or before the 20th of July next, that they may be examined and liquidated.

JOSEPH FREEMAN,

BAKER, PERTH.

Both made their way (eventually) to South Australia, which was about as far as it was safe for them to travel as the colony of Victoria had enacted some hideous laws about expirees attempting to enter that jurisdiction.

According to the laws of Victoria, any person once convicted of a transportable offence, and found residing in Victoria within three years of the full expiration of his sentence, is liable to penal servitude on the roads, either in or out of irons, for the space of three years. If, after undergoing this sentence, he remains in Victoria three months longer, he is liable to a repetition of the former sentence; and so on, as long as he lives. All property found upon him is confiscated. Any constable who “suspects” that a person resident in Victoria was sentenced to transportation, and had not, three years previously, completed his term, may apprehend him without warrant, and the burden of exculpatory proof is made to rest upon the person apprehended.

“SWAN RIVER CONYICTS.” Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 – 1904) 26 April 1856: 6. Web. 1 Oct 2024 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article161258488.

This debate in South Australia about how to treat former prisoners was ignited by the arrival of James Thompson (no relation) and others into their polity. He had been arrested for wandering the streets of Adelaide very early in the morning with no good excuse.

ADELAIDE: TUESDAY, APRIL 22.

“ADELAIDE: TUESDAY, APRIL, 22.” South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900) 23 April 1856: 2. Web. 1 Oct 2024 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49747827.

[Before Mr. C. Mann, Stipendiary Magistrate.]

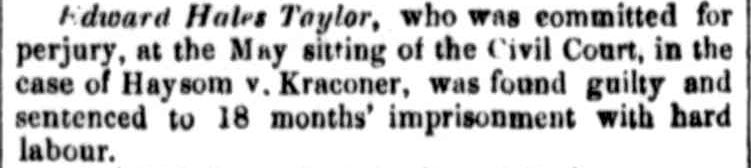

“CONDITIONAL-PARDON” MAN.— James Thompson was charged with wandering about the streets at 1 o’clock in the morning, and not giving a satisfactory account of himself. Sergeant Badman deposed that he stopped the man and his companion in Light-square, and on his refusing to give a proper account of himself, he brought him to the Station-house, as he had watched him ever since his arrival from Swan River, about seven weeks ago, and observed him under suspicious circumstances several times. On searching defendant a conditional pardon was found upon him. There were no fewer than 20 or 30 of them about the streets, and doing nothing (as far as could be ascertained) for a subsistence. The prisoner’s wife said they brought a good deal of money with them, and she had taken in washing, and her husband was going to work that very morning. She then pleaded for him, and hoped His Worship would look over the matter, as it was the first time. His Worship said he had a duty to perform. He must commit the prisoner for a week; for though it was the first time that he had been brought before the Court, the police had watched his motions for the last few weeks, and the course now pursued was necessary for the protection of the public.

Only twenty five years before, the good burghers of Western Australia were complaining about exactly the same thing concerning riff-raff from Van Dieman’s Land and NSW.

It entirely possible that this James Thompson (no relation), who is definitely the same convict formerly employed by James Dyson, is not the same individual who returned to Western Australia at some date afterwards and worked by his former master’s swamp.

Let’s now take it as read from now on that any time I invoke the name Thompson (or any of it’s variant abominations), the suffix “(no relation)” can safely be appended to it.

There were thirteen transporteés sent to Western Australia named James Thompson and four were James Thomsons. After a time, none of them are readily distinguishable from the other James Thompsons who were born free and stayed that way even if maybe some of them shouldn’t have been.

In conclusion, I have no idea who James Thompson with the paddock near Dyson’s Swamp during the 1880’s was. I don’t know his backstory, or family, or whether any of his descendents still live in Western Australia. I only know he’s not related to me.