My Favourite Bastard

There is an unwritten law that must be followed when writing about colonial Western Australian history:— It is known as Nairn Clark’s law, and historians ignore it at their peril.

There is an unwritten law that must be followed when writing about colonial Western Australian history:— It is known as Nairn Clark’s law, and historians ignore it at their peril.

A guide to the diorama of central Perth before 1880 on display in the Museum of Perth

There was nothing particularly unusual about the citizens of Perth suing each other in the civil courts during the 19th Century. It was more out of the ordinary not to be embroiled in some sort of legal action at any given moment. On Tuesday, 9 May 1854, it was publican and horse breeder George Haysom’s turn to appear before the Commissioner of court as a defendant.

Much as I would dearly love to visit Tasmania again and wallow amongst the microfilm, that’s not going to be possible any time soon. Then, thanks to a lead not affiliated with any of the “official” sources of knowledge, I learnt that a certain religious sect have in their possession the documents I seek

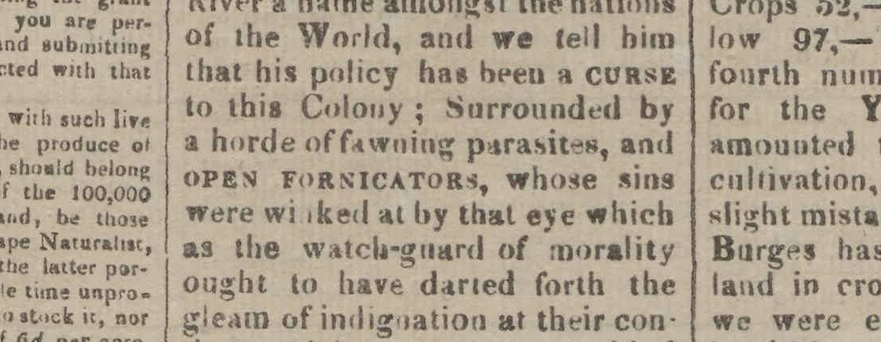

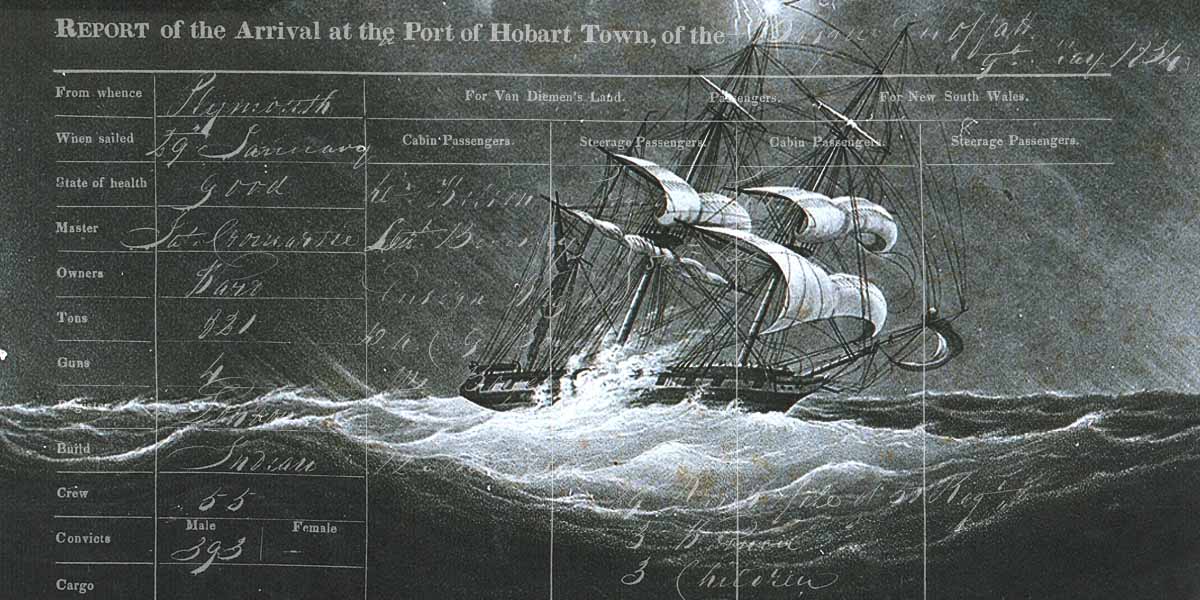

Convict James Dyson was assigned to work for the Van Diemen’s Land Establishment for all of four days between 2 and 5 October 1837. What happened next will not surprise you in the slightest.

Apart from being an inspiration to future Libyan dictator Colonel Gaddafi, there must be a whole lot more to the man than is currently understood.

Van Diemen’s Land settler William Patterson was winding up his affairs in that colony when convict James Dyson was assigned to him about 14 July 1837

The Master of Corra Linn On, or just before 7 December 1837, Henry Nickolls, master of the Corra Linn estate […]