(or Orphans of a Perfect Storm)

a more worthless set of men he had never before sailed with.”

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954) Sat 11 Jun 1853 Page 4

…Captain Benjamin Avery stated, as he stood once again before the magistrate in the Water Police Office and denounced nearly half his crew now paraded before him in the dock. Seventeen large and aggressive men shouted angrily as they were, as one, sentenced to twelve weeks hard labour in prison. They cursed their Captain in the vilest language and their threats grew louder and more violent. They had, after all, been found guilty of disobeying his orders, and one had even stuck the master and started to draw a knife on him. In a military service such as the Navy, they would have all been hanged—if they were lucky. But this was a civilian court and the three suddenly very civilian-looking Police Constables on guard duty that day began to realise that if the prisoners chose to act on any their blood-curdling threats, there was very little they could do to stop them…

What Mary Chapman, spinster, twenty-six years of age, from Carlow, in County Carlow, Ireland, thought about this ugly sequel to her journey to Australia, on the sailing ship Australia—we have no record at all. Had George Astley (her beloved) been down there waiting on the docks for her, waiting to catch sight of the lass he had not seen for two long years? He had part-paid for her passage to join him, so it would be more than slightly odd if he had not. But both would have been disappointed on that day.

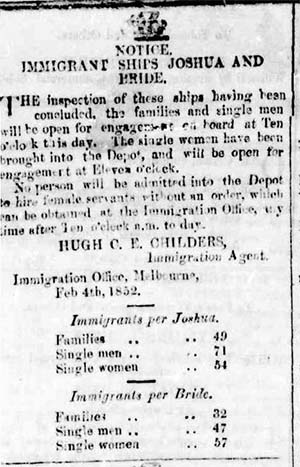

8 June 1853, as the ship Australia hove into sight of the harbour, that was the final spark which Captain Avery was unable to keep clear of his powder keg of a crew. They had been at sea for one hundred days. One hundred days during which they had been expressly forbidden from even speaking to their cargo of one-hundred-and-forty-four young, nubile, single, Irish maidens…

James McCloud was the ringleader, it seems. He struck the Captain and was about to draw his knife when his limited powers of self-preservation (perhaps) exerted themselves. The crew (not quite to a man) refused any further orders from the Captain and sat down. They hoped this would induce the Captain to dismiss them so they could jump ship and head to the gold-diggings which had probably been their plan signing on to Avery’s vessel in the first place. The Captain had soon realised that only seven out of his crew of thirty-seven were real sailors, so the remainder probably had no idea how this scheme of theirs must inevitably play out. One would suppose, so close to their destination, that all the immigrants who were able to would have crowded on the top deck for their first proper sight of their new land. Presumably they would have seen what was going down—namely their Captain and protector from the lascivious gaze of McCloud and his comrades, felled by a blow. They had travelled so far, would it really now all end here?

But Captain Avery did re-assert his authority. On shore, in the government depot some time later, Mary Chapman was interviewed by a immigration inspector and gave the same answer to the question asked of every immigrant who had been on that particular voyage.

“Any complaints reported [of] treatment on board the ship: None.”

Captain Avery had well and truly earned the bounty payment for delivery of his cargo.

Miss Mary Chapman provided some other details about her situation on the immigration form. Her “calling” was as a kitchen maid, her state of bodily health and strength was classified as “good”, as was her “probable usefulness” to the colony. Confirming that she was an orphan, and knew nothing of her own parents, the inspector would not have been surprised when she stated that she had no relatives in the colony. However, unlike most of the other immigrants from this arrival, she did not have a future employer’s address recorded against her name. Which raises an important question: Where was George Astley at this time?

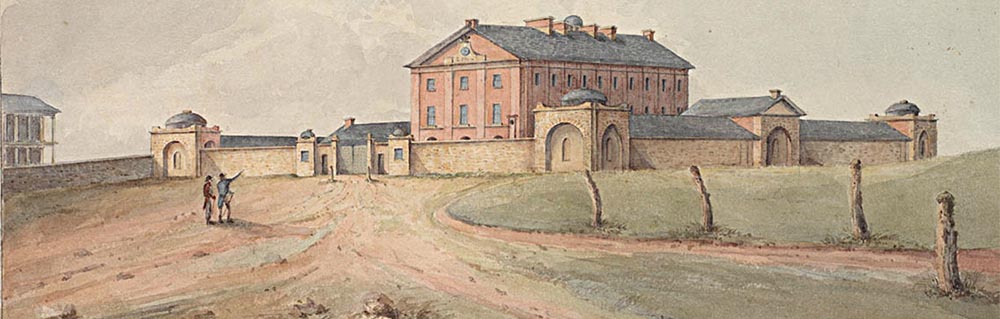

Was he outside the immigration depot gates awaiting her to walk beyond them? (its unlikely they would have let a single man in to visit a single woman. Totally inappropriate!) To re-iterate, there is a large gap in the record at this precise time, but it’s worthwhile stating just where the immigration depot Mary was probably housed was located.

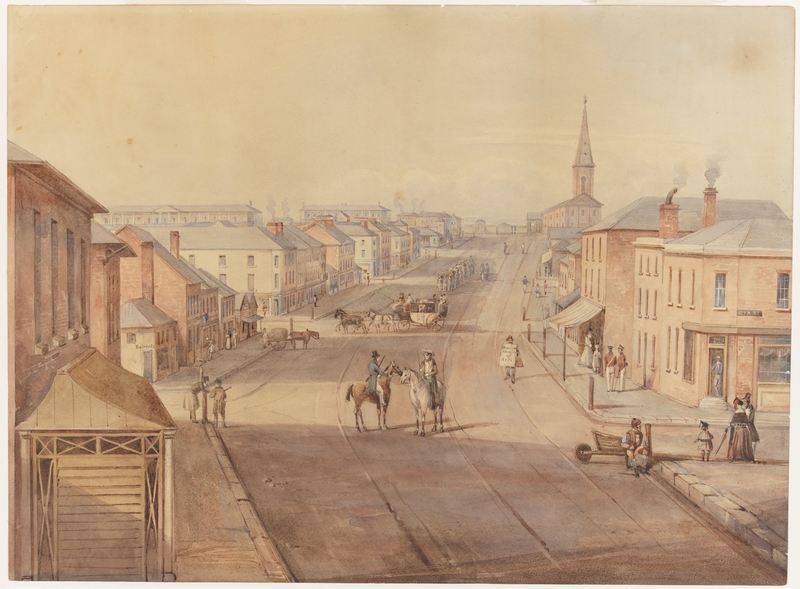

In the days after her arrival, the ship Australia was moored at Campbell’s Wharf in Sydney Cove. It is nothing less than gobsmacking to me that nearly 170 years after the fact, the warehouses associated with this wharf that Mary Chapman might have seen with her own eyes still exist in their original location between the famous Circular Quay and even more famous (much later Sydney landmark) The Opera House.

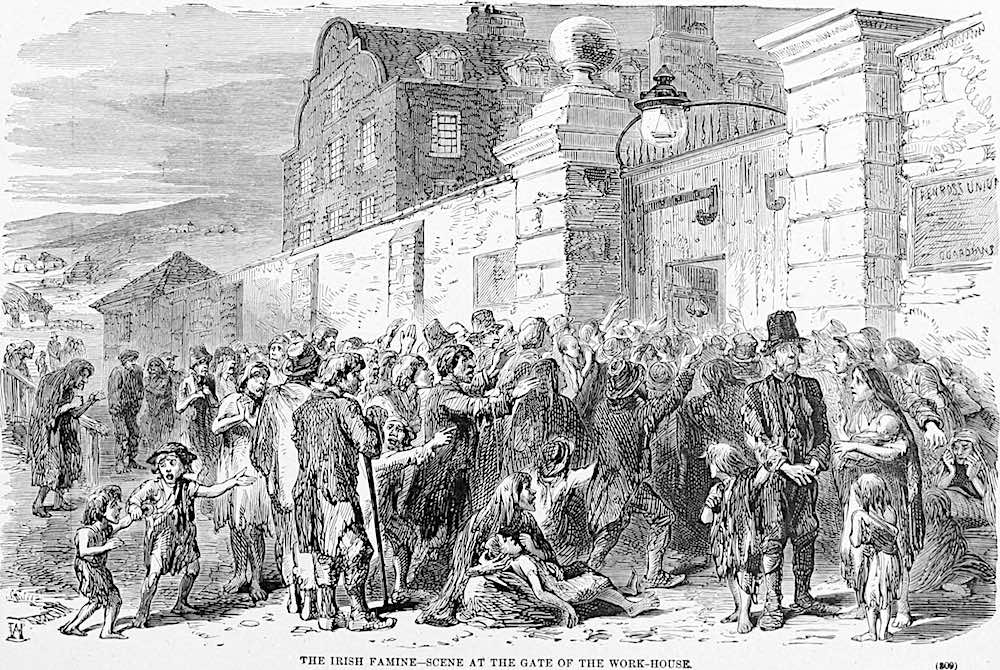

If Mary Chapman was not collected immediately by George Astley, nor was hired by some local family as a house servant, she would have been lodged in what is another miraculous survivor to the present day in the form of the Hyde Park Barracks. Now a museum, it appears to contain a permanent display for the 4114 Irish orphan girls that passed though the building, housed in a structure first built for convicts. Although Mary exactly matches the description of “Irish orphan girl”, she was not one of that particular number. But she would have matched the candidacy pretty much perfectly for the “Earl Grey Scheme” that operated between 1848-1850 during the height of the Irish Famine. She may even have been in an Irish workhouse during that time. But this immigration scheme was well and truly over by 1853 and prejudice against the Irish Catholics was one cause of its curtailment. Mary would have been housed with a non-specific cohort of female migrants recruited by immigration agents who were paid a bounty for their safe delivery. Some as yet unidentified agent was paid £1 for Mary’s arrival into Australia. How much George Astley’s contribution to the ticket fare counted for anything is not known.

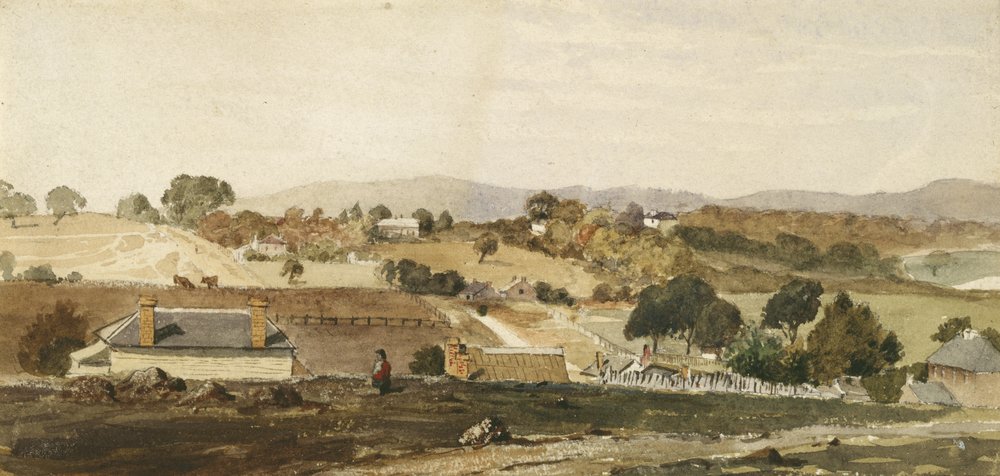

The point to be made is that Mary Chapman was now in Sydney, capital city of the self-governing British Colony of New South Wales. When last heard of, her lover was working for a punch-drunk farmer on the outskirts of Melbourne, once part of the Port Philip District of the Colony of New South Wales, but now capital of the wholly independent Crown colony of Victoria.

As a famous song of the time reminded everyone, Australia was “ten-thousand miles away” from the British Isles. Looking at a map when contemplating such a voyage, the 444 miles between the two capitals must have seemed trifling… It’s not, though. Even in this age of asphalt highways its still an all day drive by automobile and you still have to cross a mountain range.

By 1853, Astley’s employer (from the time had had stepped off the boat in Hobson’s Bay a year ago), Mr Edward Bailey (or Bayley), the Pentridge farmer, had not quite yet reached peak lunacy, but was probably well on his way there. In later years he (Bailey) would locked up for being out of his mind—this was attributed to drink. It is probably a coincidence, (as we know nothing of his parents’ actual habits), that the Astley’s future son George (defying all cultural stereotypes and societal norms) attributed his eventual long life to rarely touching alcohol.

Bailey’s mental health could not have been aided by an incident in 1856 when Mrs Bailey and he left their home for a few days to visit friends in Melbourne. In their absence, a recently dismissed employee who came from Ireland ransacked their house. I know what I’m trying to make you think, and you would be right… Miss Mary Ann M’Cormack was arrested in central Melbourne a few days hence, red-handed with all the stolen property. Regardless of the fact that I am shamelessly trying to ramp up the drama, there is next to no chance the Astleys were involved. Yes, Astleys: plural.

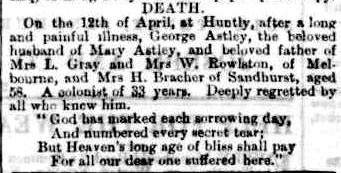

At some time in 1856 (The registration record is lost or was never created), George and Mary Astley were celebrating the birth of their first child, a daughter they called Susan. They were probably living somewhere near the present settlement of Huntly, a few kilometres north of the gold mining boom-town of Bendigo and some 142 kilometres north-north-west of Melbourne. Susan was the first of ten children they would produce together over their three decade marriage. But theirs was not a goldfields marriage.

On the 17 April, 1854, a year after arriving in Sydney—another year of uncountable travails— a ceremony took place in the Church of St James, Sydney town, conducted by the Reverend Charles F. D. Priddle, pastor of the Church of England. George Astley was married to Mary Chapman in another building that remains today— and It is worthwhile to observe that from this church’s convict-built (and designed) spire you could look down onto the Hyde Park Barracks building that was located just across the road. Their witnesses were Abraham Summons and Ann Marshall (connection with the happy couple unknown).

They had made it. They had survived. They were together. By the end of that year, by another route unrecorded, George brought his bride back to Victoria and they made their way out towards the Bendigo goldfields, one of the richest goldfields the world would ever find. There they would find their fortune. Not monetary fortune perhaps, but a home and a family who would outlive them…

…and remember them, as I do.

Postscript

SYDNEY POLICE COURT.

Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1875) Sat 11 Jun 1853 Page 5

[…]

WATER POLICE OFFICE.—Friday.—

[…]

Seventeen seamen belonging to the ship Australia, recently arrived with emigrants from Plymouth, were charged with refusing duty. Captain Avery produced the official log, containing an entry of the refusal, which had been duly read over to the men. The second mate gave corroborative evidence. The prisoners on being asked for their defence, made the usual groundless complaints of ill-treatment. They were found guilty and sentenced to 12 weeks’ imprisonment with hard labour. A disgraceful scene then took place, the men abusing the Captain in the Court, and as they were such a numerous body, and evidently reckless and disorderly characters, the position of the reporters, who were in personal contact with them, was anything but agreeable. They were ultimately removed and locked up.