Researching a Convict Ship

Researching a particular convict ship I find more that I expected. This will turn out to be a damn good chapter when everything has been assimilated.

Self explanatory?

Researching a particular convict ship I find more that I expected. This will turn out to be a damn good chapter when everything has been assimilated.

When I started writing my book on the Dyson family, very little was known about James Dyson’s first wife Fanny […]

He was born about 1807, probably in the village of English Bicknor, part of the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, an ancient western county of England near the border with Wales. He died… well that’s one of the many facts up for debate about his life.

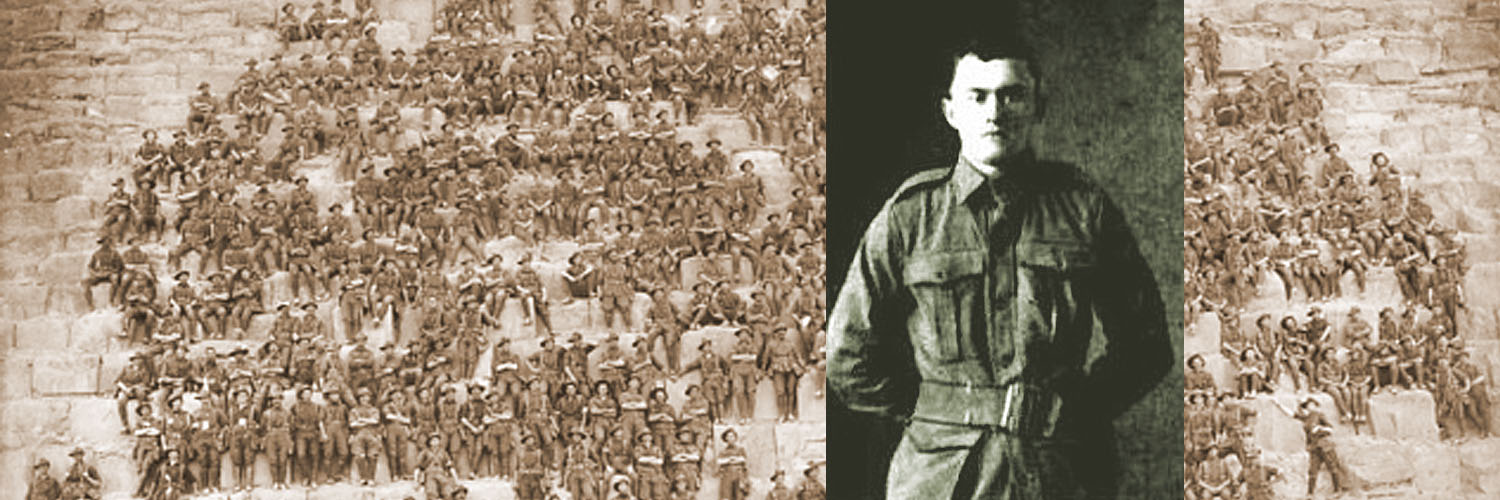

Sam Dyson was was among the first to sign up for the Great War and was among the first quota of Western Australians in the AIF. He would be one of the first on the beach at ANZAC cove, and would survive for his Dad to tell that story. His father was Andrew “Drewy” Dyson and it’s important to remember that any story mentioning Drewy will always end up being about Drewy.

There is a particular family in Australia who trace their lineage back to a William Murrells who arrived in the colonies of Australia as a young man. He married a very young lady called Emily Buffin and they proceeded to breed like rabbits. This is not their story.

My sister asked her Miss Nearly-three what sort of cake she would like for her impending birthday. Her mother hopefully […]

Help save the grave of James Dyson and his two wives in East Perth Cemetery The bodies of James Dyson […]

A reference list for the children of James, Fanny and Jane Dyson

I believe I have successfully reconstructed the baroque, Byzantine story of the first Mrs Dyson. I’m now prepared to state my theory and die on this hill if that be my fate. (Hint: I’m probably entirely wrong!)