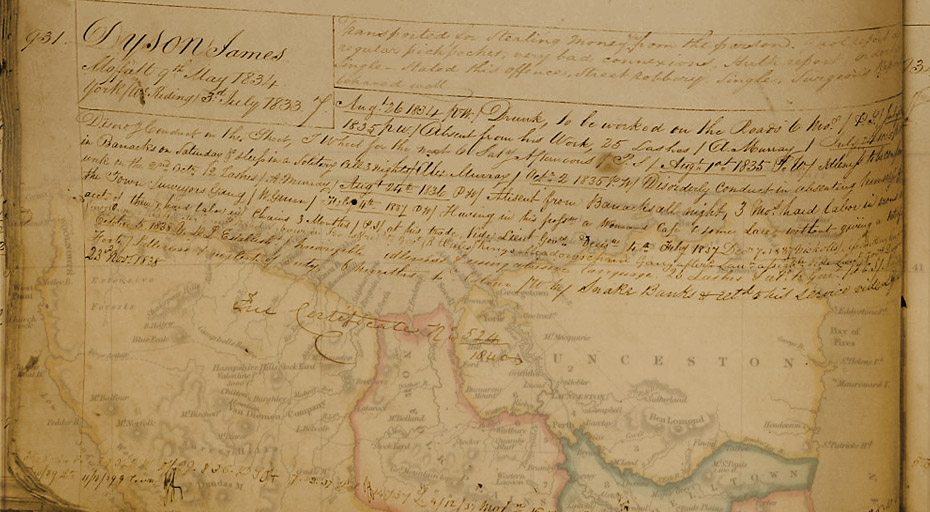

Moffatt (1) 1834

James Dyson (1810-1888), civic leader and businessman of Perth, Western Australia had also been a convicted criminal in a former life. Sentenced to seven years transportation beyond the seas in July 1833, he spent the first few weeks of his sentence imprisoned in York Castle, then four months on the prison hulk Justitia anchored off Woolwich near London on the river Thames.

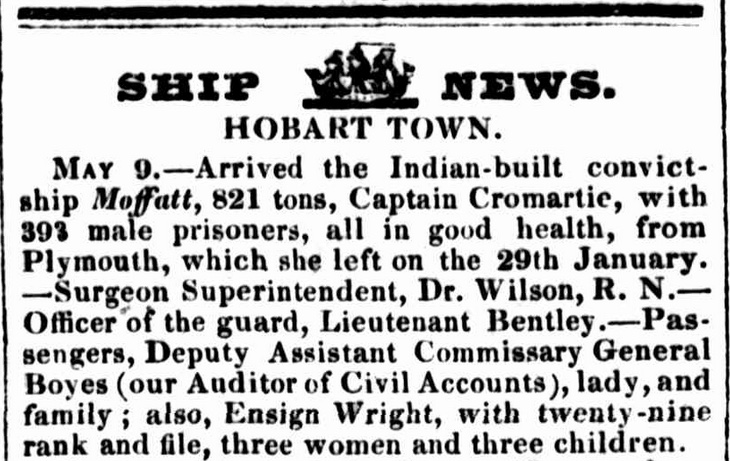

On 20 November 1833 he was bundled on to the merchantman Moffatt at Woolwich, but the formal date of sailing from England to Van Diemen’s Land was not until 6 January 1834. The port of departure was Plymouth. One hundred days later the Moffatt arrived at Hobart town in the convict colony. It was a record speed for a crossing and the vessel carried a record number of convicts within its Indian teak hull.

Of the four hundred prisoners loaded on board, 393 made it to their destination alive. Given that I would not be writing this if he had not made it — Dyson survived the voyage. Still, I would like to know more about this part of his life than what is regularly regurgitated in the standard sources.

Claim a convict: Moffatt (1834)

convictrecords.com.au: Moffatt (1834)

Moffatt hauled convicts to Australia four times — Three to Van Diemen’s Land, and one to New South Wales. Convicts were categorised by which ship and voyage they arrived on, so James Dyson was linked to Moffatt (1).

History of the Moffatt on wikipedia

This was the Moffatt’s first time as a convict transport. Prior to that, she was an East India Company ship (The British cartel that owned India for the moment) and her master for her last voyage for the EIC who also commanded her first as prison transport was a young man named James Cromarty (also spelt Cromartie). He was 28 when he became master of the Moffatt in 1832.

A brief biography of him here would be a lot more published about him than I have so far found written: — Cromarty was born on South Ronaldsay amid the Orkney islands north of the Scottish mainland. Up until the captaincy of the Moffatt for the EIC in 1832, I know nothing about him. It may have been his first command but researching this point has been inconclusive so far. Then, between 1836-1840, he captained the sailing ship James Pattison until she was lost at sea due to fire. He and all his crew were rescued. He was then master of the Chieftain (1841) and then the Equestrian (1844-1847). He married a Miss Charlotte Kelly in Sydney back in 1836. Their home was in London and they had at least two sons together. Charlotte Cromarty disappears from the record after 1847 and by census time 1851, James Cromarty has retired from the sea and taken up farming near his birthplace on South Ronaldsay. He dropped dead 13 July 1882. He was 78 years old.

Whether deliberately or by chance, Cromarty was master of many immigration voyages to the Australian colonies. Whether his passengers were free or unfree, one thing both types of voyage shared in common was the presence of a surgeon to ensure that as many of the cargo got to their destination alive as possible. After many years of trial (and mostly) error, the best way found to achieve this outcome was to ensure that neither of these parties got paid unless either gave the other a good report and the cargo arrived mostly intact. Convict ships had surgeons from the Royal Navy. On board the Moffatt during 1834, this was Thomas Braidwood Wilson, RN (1792-1843).

Thomas Braidwood Wilson in the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Unlike that for Captain Cromarty, Surgeon T. B. Wilson’s official log of the 1834 voyage of the Moffatt survives. Further more, images of the original pages are now easily available for study. Just one little problem — This tosser wrote most of his journal in Latin — a dead language only specialist scholars can now read.

Marvel at the handwriting in the Journal images on Trove

Unfortunately learning the language of the ancient Romans and the medieval church is somewhat outside my capabilities. There are some broad summaries of what the journal contains in the index of the archive where the originals are stored. The name of James Dyson is not mentioned, as far as I can decipher.

National Archives, United Kingdom

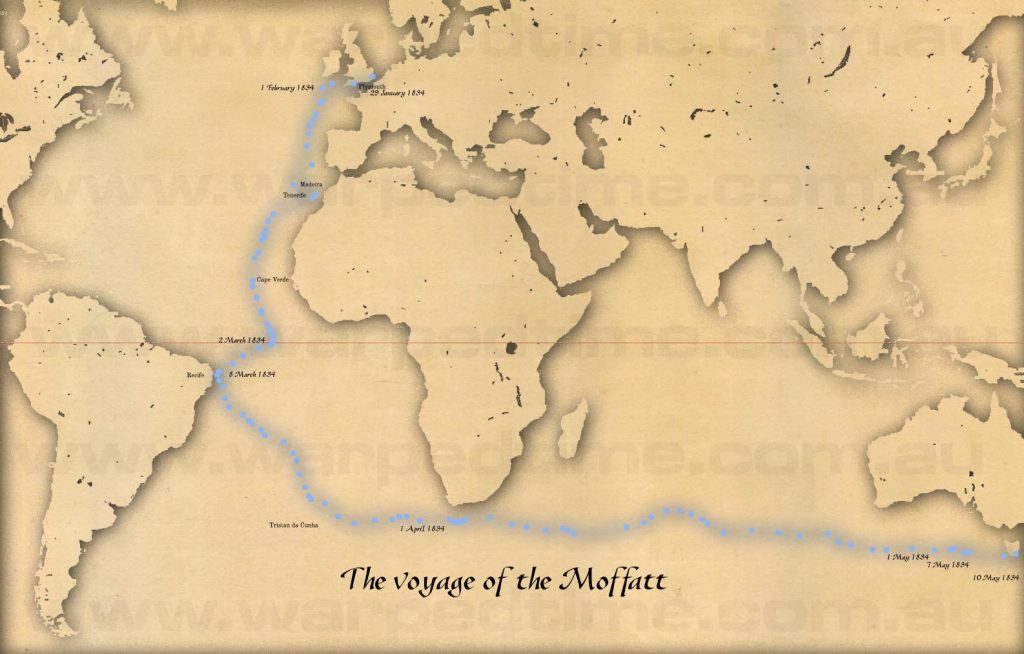

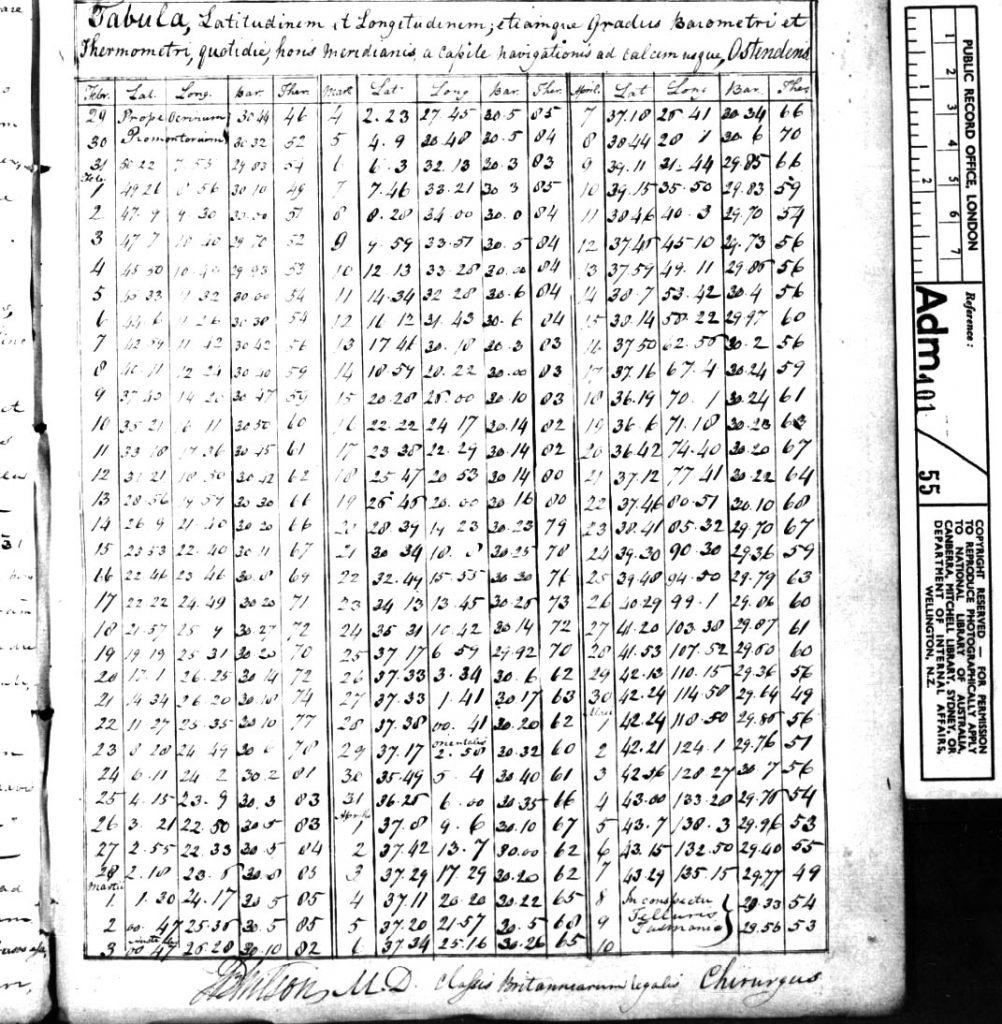

There are no convict diaries for the Moffatt. Those that I have perused date a few years earlier or later on different ships, and all describe very different conditions on every separate journey. It is very frustrating not even being able to generalise on the experience. I could not even be sure exactly what was the route the Moffatt took. However, the one useful bit I could glean from the journal was this table:—

From which I was able to generate the following map:—

Then I learnt a bit more about Surgeon T. B. Wilson. It turns out he had quite the career as an explorer — In Western Australia he named Mount Barker in the South West of the colony after his colleague Captain Collett Barker. In return, Wilson’s Inlet, near the town of Denmark on the south coast is named after him. Further more, this bastard who could not be bothered to write his official report in anything other than a language most — even then — could not read, then published a book of his travels in 1835.

Note the date: Narrative of a Voyage Round the World by T. B. Wilson was published in London only a year after he sailed on the Moffatt, and lo! There is an appendix to this tome intituled: —

Remarks on Transportation &c., &c.

AS the subject may not be unacceptable to some of my readers, I shall make a few observations relative to convict ships,—the management of prisoners during the voyage, and their disposal and treatment in New South Wales, and Van Dieman’s Land.

He then goes on to describe the same in meticulous detail, there is even a footnote in the manuscript relating to the troops guarding the prisoners on the voyage..

* Last year (1834), I had charge of 400 prisoners (the greatest number sent in one ship), without any additional guard.

Best of all, his entire publication is available on Project Guttenburg as a free ebook.

Huzzar! Now if only there were any other passengers on the Moffatt who might have written… I don’t know… a diary perhaps?

Page 2

So, who was this Deputy Assistant Commissary General Boyes when he was at home?

George Thomas William Blamey Boyes (1787-1853): Australian Dictionary of Biography entry.

So it turns out this dude was a diarist, and further more, his diaries have been transcribed and published — Oh wait, just Volume I: 1820-1832 — Thats… Oh bugger!

Fortunately for me, the rest of his oeuvre is available for download on the website of the University of Tasmania Library Special and Rare Materials Collection. The downside is that the dates I require have not been transcribed and the pdf that contains the images has been compressed almost beyond the borders of illegibility. However, now I have a complete account of sailing ship Moffatt’s 100 days at sea in 1834. All that remains for me now to translate G. T. W. B. Boyes’ thoroughly indifferent handwriting. However, at least its not in Latin.

I reckon with the aid of a Latin dictionary and an online translation program you could transcribe the Surgeon’s Journal quite easily. Give it a shot!

Thanks for the information about James Cromartie. I believe he may be the brother of Captain William Cromarty of South Ronaldsay. William was my 3 x great grandfather and said to be the first settler in Port Stephens, NSW. I’ve published a biography of William and been unable to confirm that James and he were brothers. Would you be able to throw any light on this? William was born in Cletts in 1788 and, as first officer on the brig Fame, arrived in Sydney to settle in 1822.

Hi Leslie,

Thanks for a very interesting query. I have no idea if James and William Cromartie are related but now I’d be very surprised if they were not. The only issue is how..

James is a good 16 years younger than William. I have a possible baptism record for James in South Ronaldsay as follows:—

Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950

Name: James Cromartie

Gender: Male

Birth Date: Aug 1804

Baptism Date: 13 Aug 1804

Baptism Place: South Ronaldsay, Orkney, Scotland

Father: James Cromartie

Mother: Isobella Scott

FHL Film Number: 990512

Only you can tell if these family details match up for your relative. Of course for me, James Cromartie is just the man who captained my 4 x great grandfather’s convict ship to Tasmania…

Just reading through some information about Henry Ackling, I believe is my 4 x Great Grandfather. He was in Moffatt (1) and was only about 18.

Really enjoyable post, Alan. I especially like the bits about that “berk” Thomas Braidwood Wilson (who happens to be my husband’s 4xgreat-granduncle). He’ll get a laugh out of that!

I’m curious what software/website you used to generate the map. I’d like to try that on some voyages I research.

B.

Thanks Brooke,

Just in case your husband has any concerns of bias, I’m even ruder about my own ancestors.

If I was doing the chart of the Moffat’s voyage again, I’d do it quite a bit differently today.

The map was completely hand drawn — on computer.

I could not find an easy way at the time of bulk converting Degrees, Minutes Seconds into metric Degrees, so I was doing the conversion for each point one at time (in a translator) displaying it on google maps and drawing the point on my chart.

It should be possible today to display all the points on google maps (or a competitor) using javascript, but I didn’t have the mental energy at the time to complete the process.

Something I discovered afterwards when reading Boyes’ journal what that the ship’s chronometer was faulty for at least half the voyage, so the strange gaps between some of the days could just as easily be the original readings as any errors in my transcriptions.

All the best, and thank you!